The first Africans arrive in a French settlement in Vincennes, Indiana, where they hunt and farm tobacco and wheat for the population.

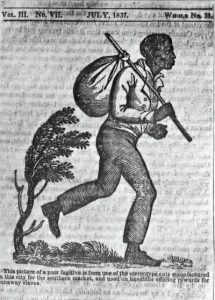

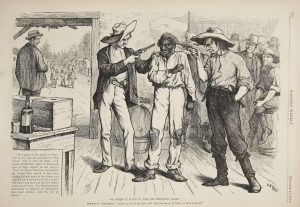

Credit: Public domain via Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora View Source