African American drivers and mechanics held the Gold and Glory Sweepstakes, an annual auto race, on the one-mile dirt track at the , typically on the July 4th holiday. At a time of rigid racial segregation in most major sporting events in the state and nation, officials did not allow African Americans to participate in the . The Gold and Glory Sweepstakes was Black America’s version of that celebrated racing spectacle. During its 11-year run (the race did not take place in 1934), the Sweepstakes was the most widely attended and the most celebrated auto racing event of its kind for African American sportsmen.

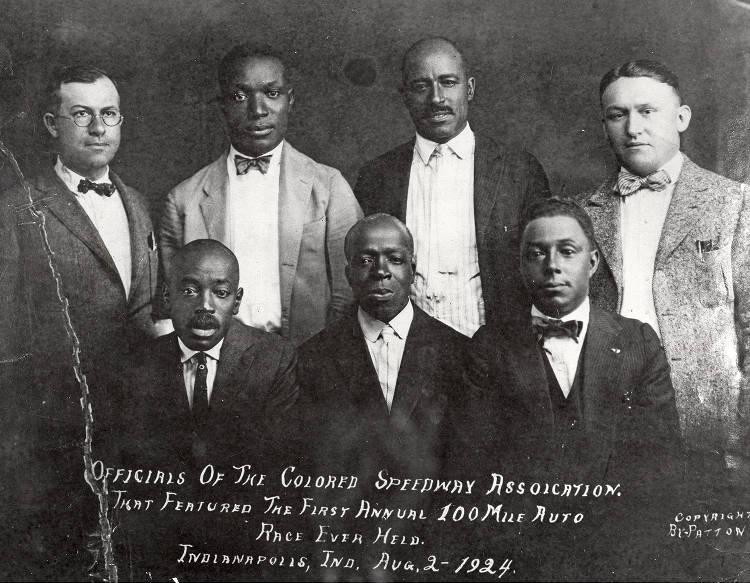

A group of Indianapolis business leaders, both Black and white, headed by William Rucker, a wealthy promoter and contractor, envisioned creating a successful auto race exclusively for Black drivers and mechanics in much the same fashion as the Negro National League had done for Black baseball players. Business leaders Harry Dunnington, George LeMon, Oscar E. Schilling, Earnest Jay Butler, Alvin D. Smith, and Harry A. Earl joined Rucker, nicknamed “Prez,” in this effort.

The race coined its nickname from a sportswriter by the name of Frank A. “Fay” Young. For the inaugural running of the event in 1924, Young anticipated that the race would be the greatest sporting event ever staged annually by African Americans, writing that “the greatest array of driving talent will be in attendance in hopes of winning Gold for themselves and for Glory for their Race.” As the Indianapolis race gained more respect and winning drivers received larger purses, other Midwestern cities created their own “Gold and Glory” events.

became the top driver and mechanic at the Gold and Glory Sweepstakes. Driving his own homemade race car, known as the Wiggins Special, he won the Indianapolis race four times (1926, 1931, 1932, 1933).

Initially, most mainstream American newspapers did not cover the annual Gold and Glory events. But within the Black press, in such newspapers as , and , coverage was extensive. By 1929, however, several national newspaper and newsreel agencies reported on the Indianapolis race.

Auto racing, then as now an expensive endeavor, suffered during the years following the Stock Market crash in 1929. Purses for regional Gold and Glory events began to shrink with the Great Depression. In 1936, a 13-car accident that ruined many racing cars and threatened the lives of several drivers, including Charlie Wiggins, marred the race. Wiggins ultimately lost his right leg because of the melee. The accident heightened the problems that the Gold and Glory circuit already was experiencing. Unable to withstand these negative financial pressures, promoters brought the racing series to an end. The Gold and Glory Sweepstakes, held on September 20, 1936, was the last.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.