As of 2020, Catholics comprised approximately 10 percent of Marion County’s population and almost one-quarter of county church membership—the largest of any Christian denomination.

Early History

The city’s first Catholics were canal workers and laborers and German artisans who arrived in the early 1830s. The bishops charged with the spiritual development of Indianapolis resided in Vincennes after 1834. At the time, the Diocese of Vincennes was the only Catholic diocese in Indiana. Until 1840, a priest periodically celebrated Mass in private homes or rented halls in Indianapolis. Among these priests were Claude François, Logansport pastor; Michael Shawe, the first priest ordained in Indiana; and French-born Vincent Bacquelin, pastor of St. Vincent’s, , who regularly visited Indianapolis beginning in late 1837.

The first parish in Indianapolis was Holy Cross, later renamed . Its church was located on the northside of Washington Street just west of West Street, on property near the present .

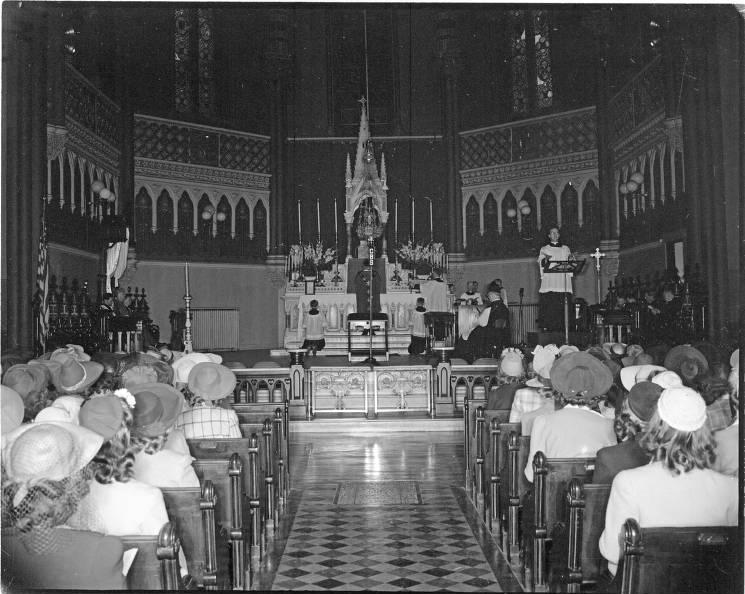

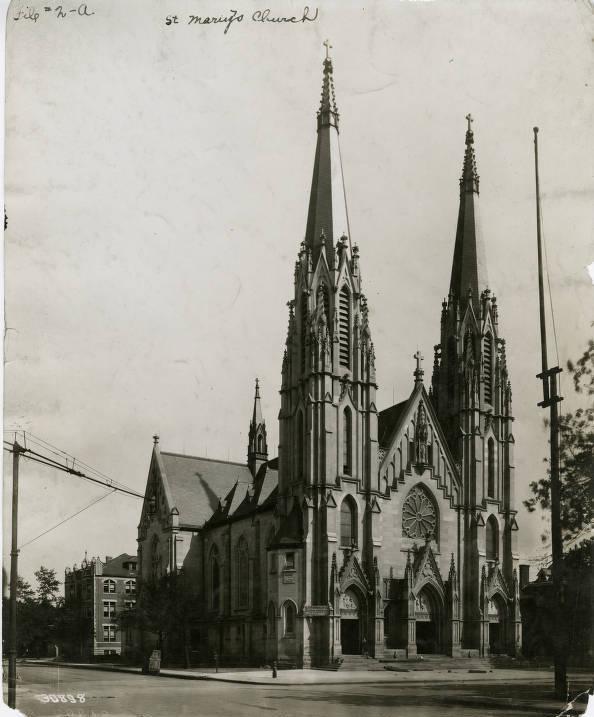

Needing a larger worship space, the Diocese of Vincennes acquired the present St. John’s site (Capitol Avenue and Georgia Street) in 1846. A growing number of believers and ethnic divisions affected St. John’s. Preferring the services of a priest who could preach in their own language, in 1858 built their own church, , then located on East Maryland Street.

Of the three new parishes organized as the city expanded south of Union Station and northeast along Massachusetts Avenue, St. Patrick (southeast, 1865) and St. Joseph (northeast, 1873) were English-speaking while Sacred Heart (south, 1875) was operated by German-speaking Franciscans.

Irish and Germans were buried in separate sections when a cemetery opened along Pleasant Run at South Meridian Street in 1862. Several religious communities were responsible for social services and education. In 1873 Good Shepherd Sisters organized an orphanage and opened a home for the aged.

Daughters of Charity started St. Vincent’s Infirmary in 1881. Although Holy Cross Brothers (South Bend, Indiana) conducted a school for boys in 1847, Sisters of Providence (St. Mary-of-the-Woods, Indiana) opened the first permanent grade school (St. John, 1859).

Sisters of St. Francis (Oldenburg, Indiana) conducted a grade school and a girls’ academy at St. Mary’s parish after 1864, Brothers of the Sacred Heart (Mobile, Alabama) opened St. John Boys School in 1867, and Sisters of St. Joseph (St. Louis, Missouri) taught at Sacred Heart after 1877.

Episcopate of Francis Silas Marean Chatard (1878-1918)

Because the Hoosier capital became a communications hub and the state’s largest urban area, Bishop took up residence in the city in 1878. Chatard was the fifth bishop of the diocese but the first born in America. He lobbied the Vatican to move the see city of Vincennes to Indianapolis. He envisioned a downtown parish away from the commercial portions of the rapidly expanding city that would serve as the seat of the Catholic center of Indianapolis. In 1890, Chatard purchased the southeast corner of 14th and Meridian streets for the episcopal residence and adjoining chapel for SS. Peter and Paul. The name, Diocese of Vincennes, was formally changed to Diocese of Indianapolis in March 1898.

Chatard was instrumental in Indianapolis’ construction as the newest diocesan see the city, forming parishes and finding priests to serve the burgeoning Catholic community. With the organization of St. Bridget’s (northwest, 1880), he completed the circle of parishes around the original St. John’s and St. Mary’s. He then moved to develop a wider concentric circle of parishes: St. Francis de Sales (northeast in , 1881), St. Anthony (west in , 1886), (the future cathedral, north, 1892), Assumption (southwest in , 1894), and Holy Cross (east, 1895). St. Elizabeth Maternity Hospital and Infant Home opened in 1915.

The arrival of small contingents of southern and eastern European immigrants and southern African Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries brought renewed ethnic consciousness, stronger lay leadership, fear of Protestant proselytization, and further organizational development. In 1892 St. Bridget opened a second school, St. Ann’s, for Black children. Parishes were founded for (Holy Trinity, 1906), (Holy Rosary, 1909), and African Americans (, 1919). With this new influx of immigrants, Catholics made up 15.9 percent of Marion County’s population in 1906 and constituted 34.5 percent of the county’s churchgoers. This figure was large when compared with the shares of the various Protestant denominations but small when compared to the over 60 percent share Catholics held in major immigrant centers like Chicago, Detroit, and Cincinnati.

Mission churches existed in , , and Valley Mills for several years. The appeared in 1870, and the first Knights of Columbus council organized in 1899. The German Roman Catholic Central-Verein (DRKCV) held national conventions here in 1878 and 1909.

Episcopate of Joseph Chartrand (1918-1933)

Individual spiritual growth and greater educational opportunities concerned Catholics during the episcopacy of . Catholic Charities also was established in 1919 to serve the needy among the faithful. When Chartrand became bishop, 31,000 Catholics were organized into 19 parishes in Marion County, 14 of which had been founded during Chartrand’s episcopate.

Chartrand actively recruited young people for the clerical and religious life and encouraged the laity to receive the sacraments frequently. He welcomed the Carmelites, who established a cloister here in 1932. His founding of Cathedral High School (1918) increased both college attendance and Catholic participation in the city and professional community.

The greatest threat to Catholics occurred during the 1920s when the attacked them for their alleged immorality, anti-democratic tendencies, and allegiance to a foreign power. A strong-willed individual, Chartrand set an example that encouraged pastors and laypeople to emulate him. Consequently, they turned parishes into devotional, educational, and social centers, undoubtedly a response to the public intimidation and private prejudice against Catholics prevalent during the Klan era of the 1920s.

The , the Catholic Information Bureau (established 1924 in Indianapolis), and the American Unity League (headquartered in Chicago) also refuted Klan propaganda through their own publications. For example, the Unity League’s newspaper published the names of over 12,000 alleged Klansmen who resided in Indianapolis.

Episcopate of Joseph Elmer Ritter (1934-1946)

The administration of Bishop stabilized diocesan finances, which had been adversely affected by the Great Depression. By the time that Ritter became bishop, Catholic’s made up 22.6 percent of the county’s churchgoers, a decline of over 10 percent from 1906. Yet Catholics became more outward-looking: they formed lay organizations like the National Council of Catholic Women and Catholic Youth Organization and supported an outreach program to the Black community. Catholic hospitals and schools began to admit Black patients and students.

The city’s only Catholic institution of higher learning, , opened as a college for women in 1937. Indiana’s Catholic schools that had faced exclusion, along with African American schools, finally gained membership in the (IHSAA) in December 1941.

Ritter became the first archbishop of Indianapolis in 1944 when Indiana was designated as an ecclesiastical province and the diocese was raised to an archdiocese. Marion County had 26 Catholic parishes and 6 high schools at the end of World War II.

Episcopate of Paul C. Schulte (1946-1970)

Following world war II under the leadership of Archbishop (1946-1970), Catholics emphasized parish formation and educational expansion. The number of Catholic residents more than doubled, from 44,000 in 1940 to 92,000 in 1960. Twenty new parishes were commissioned during Rev. Schulte’s tenure as archbishop, primarily located in the suburbs of the city. The number of parishes increased to 43. The bishop even had his own church design of choice dubbed the “Schulte special.” The mid-century modern, bare-bones design of the church buildings he commissioned was his chosen favorite because he believed the design cut down on architectural fees and reduced competition for building bids.

The last concentric circle of parishes, by then in suburban areas, was completed when was established on the far southside in 1965. A $2 million school fund drive in the 1950s helped finance the building of four archdiocesan high schools: Scecina (east, 1953), Chatard (north, 1961), Ritter (west, 1964), and Roncalli (south, 1969). The Latin School opened to educate teenagers interested in the priesthood (1955); Benedictine Sisters conducted Our Lady of Grace Academy in (1956); Jesuits opened Brebeuf on the far northside in 1962. By 1970, Indianapolis had 11 Catholic high schools. Marian College admitted men after 1954. During Schulte’s episcopate, Indianapolis had three Catholic mayors— (1948-1950), (1950-1951, 1956-1959), and (1964-1967).

Changes with Vatican II

The new emphases and reforms of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) affected the local church in the closing years of the Schulte era and during the episcopates of (1970-1979) and (1980-1992). When O’Meara became bishop, Catholics again comprised over one quarter (27.2 percent) of the county’s churchgoers, but the number of priests and religious in parish life was in decline. During O’Meara’s tenure as bishop Catholic, education was reevaluated, and laypeople found new avenues of service in the parish and in the classroom.

Because of the emphasis on shared responsibility, parish councils were established to advise pastors on local needs, from the Sunday Mass schedule to financial policy. At the archdiocesan level, clergy and religious formed their own groups (Indianapolis Priests Association, 1967, and Association of Religious in the Indianapolis Archdiocese, 1968). New bodies advised the archbishop: Priests’ Senate (1971, later the Council of Priests) and Archdiocesan Pastoral Council (1990).

As the city’s population growth resulted in the multiplication of parishes, the decline of the inner city affected existing parishes and institutions. Old St. Joseph’s closed in 1949, St. Francis de Sales in 1983. St. Catherine and St. James consolidated as (1993). Eight high schools closed, merged, or moved to a suburban location. Twelve elementary schools were consolidated into three larger units: Holy Cross Central, All Saints, and Central Catholic.

In order to revitalize the Catholic presence and encourage inter-parochial cooperation in the inner city, the Urban Parish Cooperative was formed in 1984. The Hispanic ministry was centered at St. Mary’s. The Urban Parish Cooperative worked to situate the Catholic Center at 14th and Meridian streets (1982), to renovate the Cathedral (1986), and to establish homes for senior citizens and abused women.

On the grounds of the old Cathedral elementary school, the archdiocese opened the for AIDS victims in 1987, showing renewed commitment to the city center. The Damien Center was named after Rev. Joseph Damien Deveuster, a Catholic priest in Hawaii who was known for working and caring for lepers in the 19th century and canonized by Pope Benedict in 2009. Opened at the height of the AIDS epidemic, the center has been a collaboration of resources from the Catholic archdiocese and the Episcopal diocese.

The 1990s and 2000s

In the early 1990s, the 84,000 Catholics of Marion County, comprising 10.5 percent of the city’s total population and 23.3 percent of church membership, were well integrated into Central Indiana’s professional, business, and political worlds. The suburban sprawl, however, resulted in reduced membership of the center township parishes. In 1991 under the direction of the Most. Rev. Edward T. O’Meara, the archdiocese administered a committee report to determine the sustainability of Marion County parishes going into the next century. The task force assembled by O’Meara proposed plans for the archdiocese that included recommending parish closures and redistributing staff and available priests to adjust to the population decline in the city and growth in the suburbs.

Indiana native Daniel Mark Buechlein, O.S.B., was installed as the fifth archbishop on September 9, 1992, after the sudden death of Rev. O’Meara in January. Buechlein brought his immense experience in strategic planning to the archdiocese, which was in desperate need of restructuring. When he arrived, the archdiocese was operating with a $2 million-dollar deficit. With Buechlein’s help, the archdiocese was able to merge center township parishes, along with several elementary schools, to allow the remaining to thrive. By 2004, the archdiocese was again operating with a surplus of funding. Buechlein focused on improving each Catholic school’s overall performance, which resulted in an increase of 30 percent enrollment.

Buechlein retired after a stroke in 2011 and Rev. Joseph W. Tobin was installed as the sixth archbishop of Indianapolis. Tobin only served Indianapolis for four years but made a large impression during that time. In 2015, Tobin openly defied Indiana governor and future Vice President Mike Pence in allowing Syrian refugees, despite security concerns, to settle in Indiana through various Catholic charities. Tobin was known for his focus on social justice issues, for example, reaching out to Pence in defense of inmates on death row. Tobin’s tenure was short-lived as he was named by Pope Francis as a cardinal in 2016 and assigned as the archbishop of Newark, New Jersey.

Archbishop Charles Thompson was installed as the seventh archbishop of the archdiocese after Tobin’s reassignment in 2017. Thompson’s appointment at 56 made him the youngest ever in the diocese. His greatest impact to date has been his strict implementation of a “morality clause” that forbids married LGBTQ couples from being hired throughout the archdiocese. The morality clause was implemented in employment contracts starting in 2017. Tobin’s enforcement of the employment contract’s clause has made national headlines and been the subject of several pending lawsuits after three teachers in the archdiocese were fired when their homosexual marriages were forced out in the open through anonymous informants. Two additional employees were fired for their support of gay educators.

Although Thompson maintained that the church was not targeting gay marriage, he stated that the archdiocese considers all employees within the archdiocese to be “ministers” of the faith, regardless of the subjects they teach, and expects them to abide by Catholic teachings. On July 8, 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court held in a California case, Our Lady of Guadelupe School v. Morrisey-Berru, that the “ministerial” exception bars Catholic school teachers recognized in a minister role from bringing employment discrimination claims. In the summer of 2020, Thompson implemented policies that effectively banned transgender students from parish schools. The debate revealed some dissension among parishioners required to choose between canonical teachings and individual views of human rights.

As of 2020, the archdiocese was organized into 126 parishes (of which 3 were predominantly African American), a Byzantine congregation, and a Korean mission (founded 1991). They operated 68 elementary, middle, and high schools and Marian University. Two hospitals ( and ) and two homes for the aged (St. Augustine and St. Paul Hermitage) served the sick and elderly. Fatima Retreat House, Beech Grove Benedictine Center, and St. Maur Hospitality Center provided facilities for individual spiritual renewal.

The weekly archdiocesan newspaper is the , which succeeded the (1910-1960) in 1960. Over 60,000 households throughout the state subscribed to the in English, and in Spanish as of 2020. It appears in print and an online version.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.