The best-known early efforts to foster reading and libraries in Indianapolis were the Union Sabbath School founded in 1823; the Marion County Library, a subscription library established in 1844 under the provisions of the 1816 Indiana constitution and housed in the county courthouse; and township libraries set up through a school law passed by the Indiana legislature in 1852.

None of these early libraries achieved much success since they were poorly housed, frequently had no one responsible for their care, and no money was provided for their maintenance and expansion. The real impetus for change came on Thanksgiving Day, 1868, when the Reverend Hanford A. Edson, pastor of the , delivered a sermon in which he issued a plea for a free public library in Indianapolis. As a result, 113 citizens formed the Indianapolis Library Association on March 18, 1869, with subscribers paying $150 each in annual installments of $25 for stock shares in the association.

The next year, under the leadership of , the superintendent of public schools, eight public-spirited citizens drafted a revision of the existing Indiana school law to provide for the maintenance of free public libraries controlled by a board of school commissioners. Their effort met with success when the Indiana General Assembly passed the School Law of 1871 empowering school boards to levy an additional tax for the purpose of establishing and maintaining public libraries.

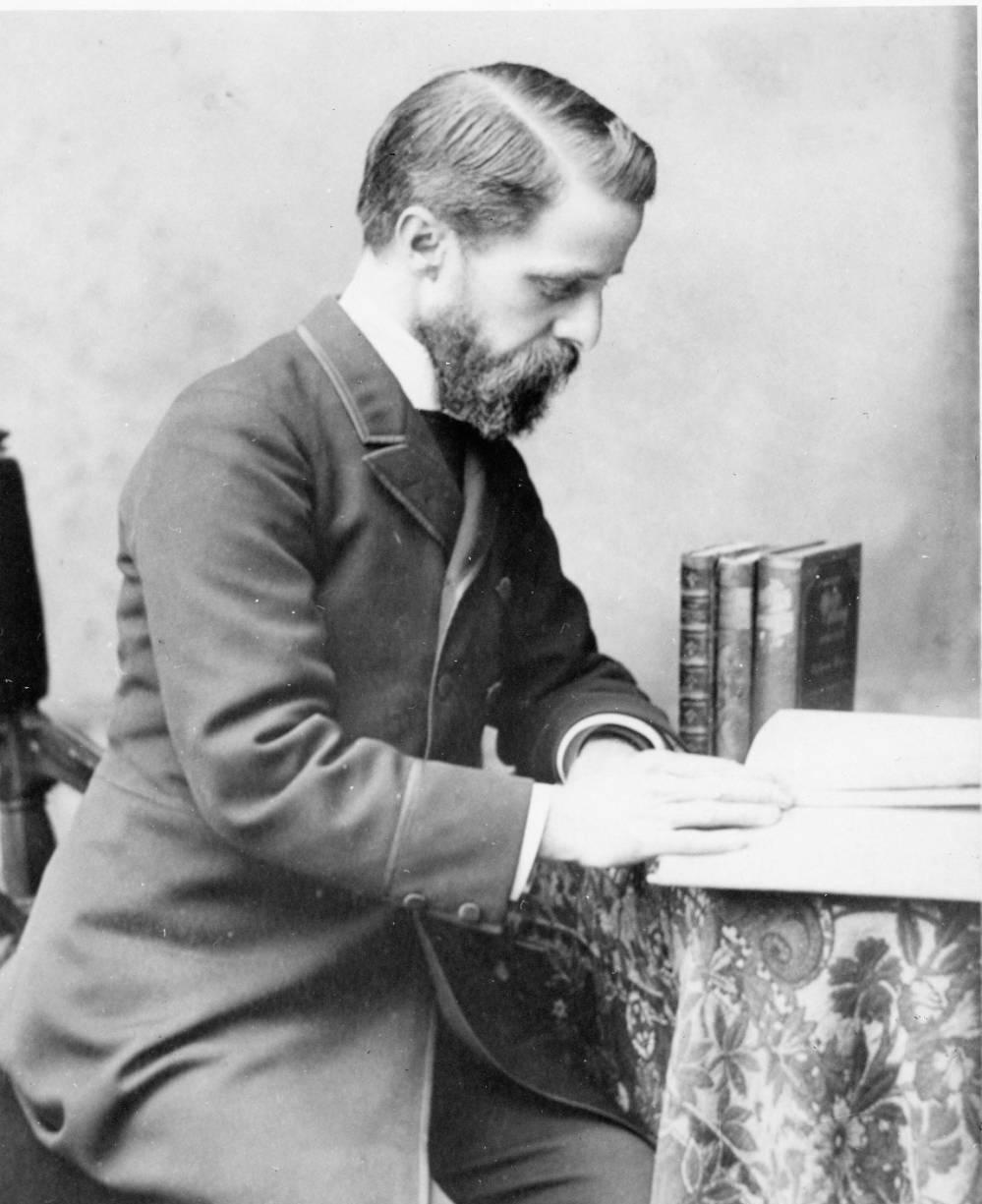

In July 1872, the public library committee of the school board hired Cincinnati librarian William F. Poole to compile a list of 8,000 titles as a nucleus collection for the new Indianapolis library. The committee also selected of the Boston Athenaeum as the first librarian.

The library, located in one room of the high school building at the northeast corner of Pennsylvania and Michigan streets, opened on April 9, 1873. It had 12,790 volumes ready for 500 registered borrowers, including the collection of 3,649 volumes given by the Indianapolis Library Association. Later locations of the library were the Sentinel Building on the Circle (1876-1880) and the Alvord House at Pennsylvania and Ohio streets (1880-1893).

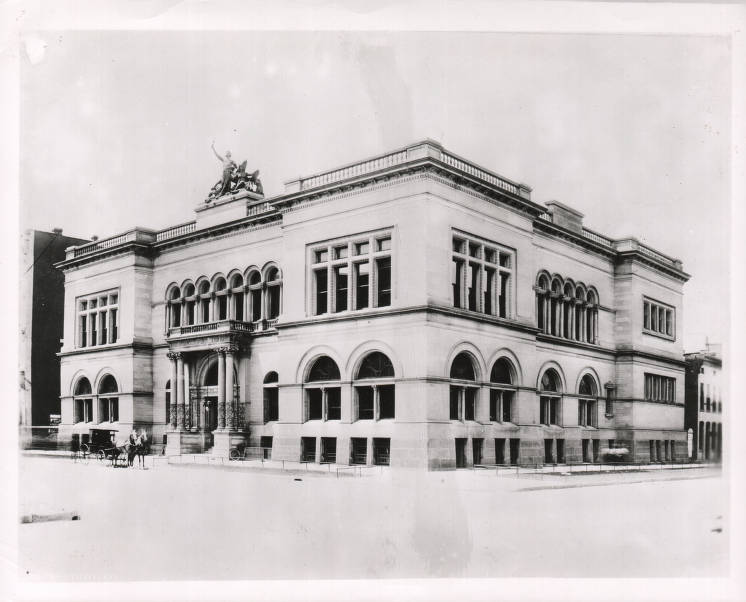

Evans served as librarian until 1878, and again from 1889 to 1892. His outstanding contribution to scholarship was his , a chronological guide to all publications printed in the United States from 1639 to 1820. Evans’ successors were Albert B. Yohn (1878- 1879), Arthur W. Tyler (1879-1883), and William de M. Hooper (1883-1889). Eliza G. Browning, a member of the library staff since 1880, succeeded Evans in his second tenure, holding the position of librarian from 1892 to 1917. In 1893, the Indianapolis Public Library moved to the first building constructed primarily for its use, located on the southwest corner of Ohio and Meridian streets.

In December 1896, the first branch library opened. Between 1910 and 1914, five branch libraries were built with a grant of $100,000 received from Andrew Carnegie. Two of these libraries—Spades Park and East Washington branches —are still in use. Prior to her resignation Browning completed work on a new Central Library located on land donated by at St. Clair between Pennsylvania and Meridian streets. Designed by Philadelphia architect Paul Cret, this impressive Greek Doric style structure, built of Indiana limestone on a Vermont marble base, opened October 8, 1917, and remains in use today.

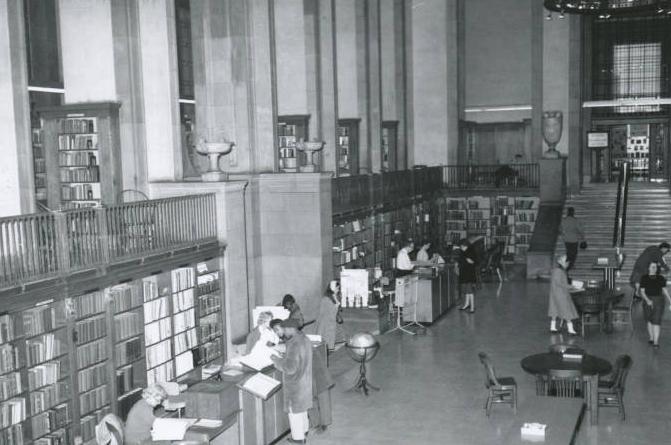

The main reading room (100 feet by 45 feet) just inside the main entrance is noteworthy for its two flights of Maryland marble stairs, two 30-foot diameter bronze light fixtures, and the ornamental ceiling, designed by another Philadelphia architect C. C. Zantzinger, which includes oil-on-canvas medallions and printers’ colophons accompanied by a series of bas-relief plaster plaques portraying the early history of Indiana.

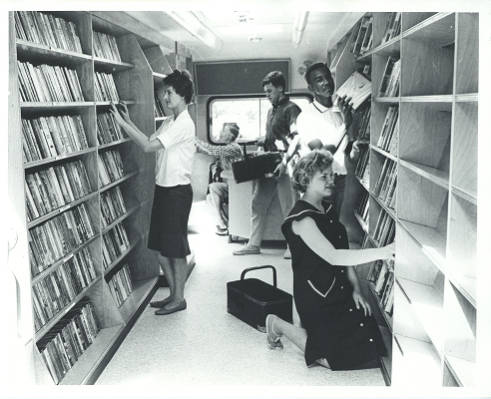

Charles E. Rush succeeded Browning, serving as librarian from 1917 until 1927. His successors were Luther L. Dickerson (1927-1944) and Marian McFadden (1944-1955). During this 38-year period, eight new branch libraries were opened, films (1944) and phonorecords (1948) were added to the library’s borrowing collection, bookmobile service began (1952), and newspapers on microfilm became available for public use (1940s).

Harold J. Sander, who served as the director from 1956 to 1971, undertook a reorganization of the Central Library in 1960 that departmentalized all adult materials and services. He also presided over the opening of 10 new branch libraries.

Prior to 1966, the library served only the School City of Indianapolis (that is, the area served by ). Over 200,000 Marion County residents outside of the city limits had no access to free public library services. From 1966 to 1968 a newly formed Marion County Public Library Board contracted with the Indianapolis Public Library for service to county residents.

In June 1968, the Indianapolis Board of School Commissioners divested itself of the responsibility for library service that it had held since 1873. The city library then merged with the county library, establishing the new Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library as a separate municipal corporation serving all of Marion County except and .

A seven-member board governs the library: two members are appointed by the City-County Council, two by the Indianapolis Board of School Commissioners, and three by the county assessor, auditor, and treasurer acting jointly as appointing authority under provisions. Funding for library services is derived from property tax, financial institution tax, vehicle excise tax, fines and fees, and miscellaneous income.

Raymond E. Gnat succeeded Sander as library director in 1972. A 40,000 square-foot Central Library Annex was completed in 1975. A major branch library building program began in 1982 and continued through that decade. A Central Library restoration fund drive was launched in 1984 with restoration work (which included cleaning and repainting the main room ceiling) completed in 1988, and computerization of major library functions was completed between 1982 and 1991.

A series of branch building updates were undertaken in the late 1990s, and a new series of updates and building replacements continue to the present day. Successive Library Executives since Gnat’s retirement have been Edward M. Szynaka (1994-2003), Linda Mielke (2004-2007), Laura Bramble (2007-2012), and M. Jacqueline Nytes (2012-2021).

In 2007, the transformed Central Library opened after the demolition of the mid-1970s annex and the stacks. The resulting -designed steel and glass tower surrounds the historic 1917 building providing a combined 293,000 square feet of space with a 398-space underground parking garage. With its 2007 renovation, the main reading room became known as the Simon Reading room and is used as rental space for special events. Reading rooms at the top of each staircase have wood paneling above oak bookcases and large leaded-glass windows. The R. B. Annis West Reading Room became home to the , which was unveiled in August 2017.

In 2016, the Indianapolis Public Library system expanded its geographic footprint in a merger with the Beech Grove Public Library, which had been omitted from the system in 1968. The system is comprised of Central Library and 23 branches plus two large bookmobiles and five Itty Bitty bookmobiles. In 2019, the library system served 3,474,067 walk-in visitors while the 280,183 card holders borrowed 7,825,981 physical items (books, DVDs, and CDs) and 1,826,964 eBooks and downloadable items. The 100th annual Summer Reading Program welcomed 46,040 participants who read 860,171 books.

A library-commissioned study conducted by Thomas P. Miller & Associates, an Indianapolis-based strategic planning and consulting firm, concluded that Indianapolis Public Library provides the community a $3 return in services for every $1 of taxpayer investment.

In 2021 several library staff members alleged racism within Indianapolis Public Library. Following stories on the accusations by the Indianapolis Recorder and the Indianapolis Star, Central Indiana Community Foundation announced in August that it was withholding further funding until a library board-led study, scheduled for December 2021, was available and an acceptable plan was in place to address any findings of concern.

Unrelated to the library staff’s allegations of racism, on April 1, 2022, the Center for Black Literature and Culture (CBLC) unveiled the names of 10 racially diverse literary greats engraved in the limestone outside the CBLC in the Central Library. The authors join the 76 original authors (70 white males, one Persian male, and 5 white females), whose names have adorned the limestone since the library’s 1917 opening. A longtime library patron and donor planted the seed to correct the distorted visual narrative almost twenty years ago. After a two-year process, the CBLC and a project committee whittled down a list of 300 authors to 10, dating from the pre-Civil War to the contemporary era.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.