African Americans have engaged in business activity since the earliest days of Indianapolis. Early in the city’s history, Black entrepreneurs usually operated as independent contractors or sole proprietors and primarily served a relatively small African American community. Until the Civil War, Indianapolis had just under 500 African American residents. By 1870, however, the city’s Black population had increased dramatically to 2,931. Most settled along the western edge of the .

Early Business Leaders

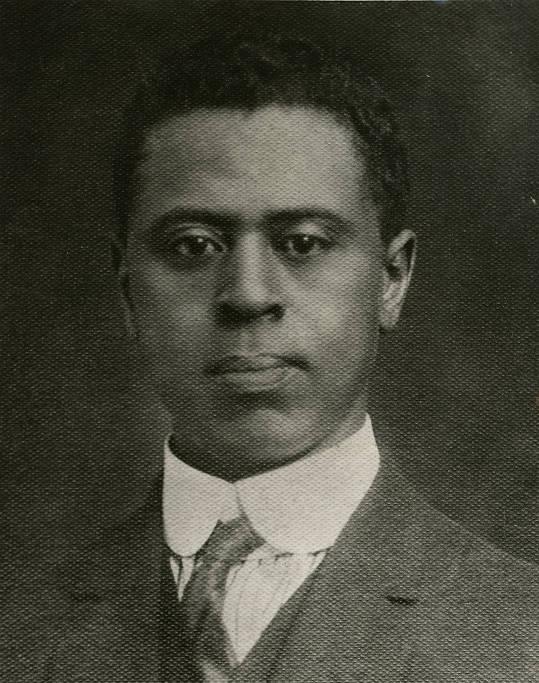

Notable early examples of African Americans in business included Anderson Lewis (1838-1905), an ex-enslaved person who was a successful carriage maker, and (1834-1892), who owned a real estate business and became the first African American elected to the Indiana House of Representatives in 1880. One of the most prominent Black business leaders of the era was Henry L. Sanders, who opened a uniform manufacturing company in 1889 that grew to have more than 40 employees.

Early Newspapers

Historically, Black business activity in Indianapolis reflected the growth of the African American population. After the Civil War, the city’s Black population grew rapidly and reached, 15,391, or 10 percent of the total by 1900, higher than the national average.

As part of this developing business community, several African Americans began businesses within the city; at least four of them were newspapers. The earliest on record was the , first published during the late 1870s by three educator brothers—James, Benjamin, and . The (Levi Christy and Alexander Manning, publishers); the (Louis Howland, Edward E. Cooper, and George Knox, publishers); and the (George P. Stewart and Will Porter, publishers) succeeded the Leader. Stewart was typical of African American business owners in Indianapolis during the late 1800s. He was politically and socially engaged in his community, and he used his activities to promote his newspaper and print shop.

Several other newspapers started and folded during the first half of the 20th century, including the Indiana Herald Times (Opal Tandy) in 1957 (changed to the in 1960). Some white-owned businesses advertised in African American newspapers, while many others refused to serve Black customers. This inattention to Black consumers gave Black newspapers almost exclusive coverage of the African American market.

Business in a Tight-knit Segregated Community, 1880s-1950s

Most African American businesses continued to be sole proprietorships throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. Service enterprises especially enabled Blacks to provide employment to other African Americans, as well as to create business opportunities for individuals. Economists studying the character of African American businesses have defined this development as a “racially interlocking market.”

By 1900, a substantial African American business community existed as revealed in a list of businesspeople compiled and published by Stewart in the (December 21, 1901). Occupations included plumbers, dressmakers, shoemakers, contractors, junk dealers, grocers, barber and beauty shop owners, blacksmiths, carriage makers, morticians, paperhangers, physicians, attorneys, dentists, and musicians. Restaurants, newspapers, hotels, saloons, and other black-owned institutions were listed, as were less-common occupations including a veterinary surgeon, a milliner, and a clairvoyant.

Increasingly, a number of skilled occupations moved toward professional status, much as happened elsewhere. By the early 1900s, an emerging class of Black professionals opened their own practices, such as Dr. (1832-1902), the state’s first Black licensed doctor, and (1854-1928), the city’s first African American licensed attorney.

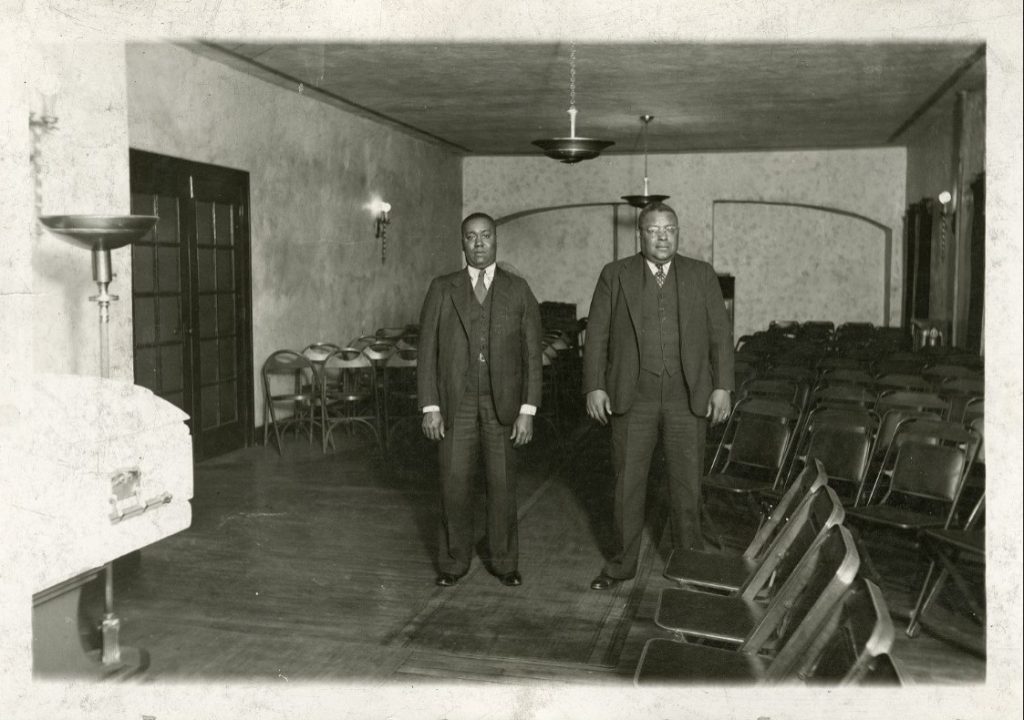

African American funeral directors also became prominent entrepreneurs, with George Woodford and John J. Thornton working in the 1880s as the city’s first Black undertakers. In 1890, Cassius M. Clay Willis established the first permanent Black funeral home, Willis Mortuary, which remained in business for over a century—until 2009.

Rigid racial segregation, often enforced by local regulations, kept most Black businesses from soliciting white customers or joining professional associations. African Americans formed their own organizations, such as the Indianapolis chapter of Booker T. Washington’s National Negro Business League.

Poverty, a lack of opportunity for formal business training, limited access to capital because of discrimination, and restrictive covenants in real estate and business licensing continued to limit opportunities for Blacks in the first decades of the 20th century. Nevertheless, some historians have designated the period from 1900 to 1930 as the “Golden Age of Black Business.” Nationally, Booker T. Washington founded the National Business League in 1900, and W. E. B. Dubois and John Hope called the “Talented Tenth” to engage in the economy. In Indianapolis, the first quarter of the 20th century witnessed the development of new businesses owned by Blacks, as well as the continuation of earlier enterprises. Most of the city’s Black businesses were located on and in surrounding neighborhoods, which was the heart of the African American community until the 1950s.

In 1910 (1867-1919), founder of a national hair cosmetics company, moved her business to Indianapolis. She was attracted to the city’s access to railroads, its central shipping location, and the skilled labor force. Her lucrative business developed an international reputation. The first African American woman to become a millionaire, Walker has been identified as one of the most “imaginative and successful” Black capitalists of the first decades of the 20th century in the United States. The Madam C. J. Walker Company remained in the Walker family until it was sold in 1988.

Walker also provided a notable example of community philanthropy by funding a and commissioning construction of the on Indiana Avenue. Completed in 1927, it housed offices, a beauty shop, a coffee shop, a drug store, a ballroom, and a popular movie theater. In fact, the Walker Building anchored an area that became the economic and entertainment center of the African American community.

Another manufacturing company, Martin Brothers, was incorporated in 1922. James, Samuel, and Jesse Martin owned the company, which manufactured and sold heavy cotton duck clothing, khaki and novelty uniforms, and other garments. Marion Stuart started his moving and storage business in 1936. The post-World War II period recorded the development of several groceries, service garages, cleaners, nightclubs, billiard halls, and restaurants owned by African Americans. Winston Janitorial Service was founded in 1953. It was Indianapolis’s largest employer among minority-owned businesses in the early 1990s.

Between 1950 and 1960, the Black population of Indianapolis grew by 34,000, which expanded the traditional customer base of African American businesses. However, racial segregation still prevented most Black residents from gaining white patrons or joining professional associations, boards and commissions. For example, the Indianapolis Board of Realtors did not admit its first Black member, , until 1965. That same year, however, the was formed to accelerate civil rights legislation and increase economic opportunities for African Americans.

Displacement and Racial Conflict, 1960s-1970s

During the late 1960s, a massive urban renewal program and construction of the interstate highway system displaced many Black-owned businesses and homes near downtown. These events disrupted much of the traditional economic activity in the Black community of Indianapolis. Moreover, the decline of residential segregation that began in the 1970s and the increased integration of the Black middle class resulted in a dispersal of African American purchasing power. Although it mirrored a national trend, Indianapolis Blacks no longer existed in a tight-knit business community that encouraged economic strength. This change at times led to racial conflicts, such as in 1993 when the local Black Panther militia boycotted a Korean merchant’s beauty supply store in a predominantly Black neighborhood.

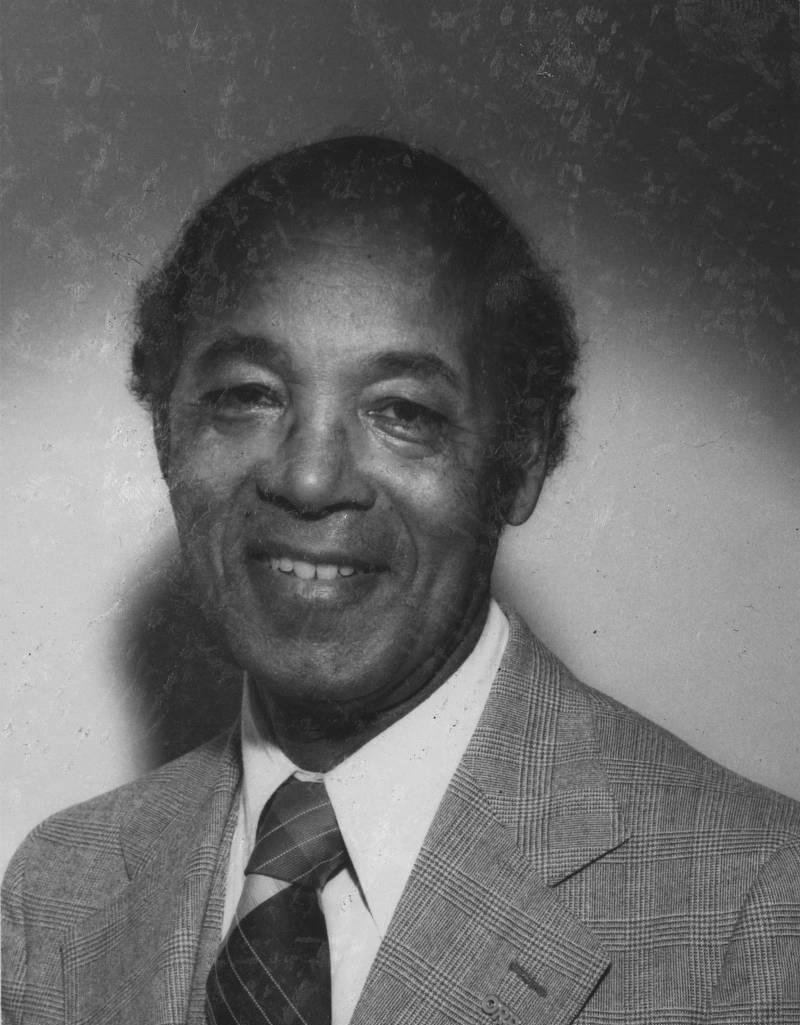

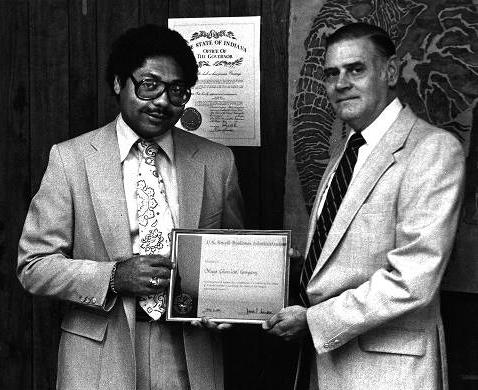

In 1972, the Indiana Regional Minority Supplier Development Council (IRMSDC) was formed to increase corporate contracts for minority- and women-owned businesses. Under its first president, Donald E. Jones Jr., the council increased sales for minority-owned businesses and broke down some of the institutional barriers they faced.

The New Generation of Entrepreneurs, 1980s-2000s

During the 1980s and 1990s, a new generation of African American entrepreneurs emerged. Perhaps the most prominent of these Black business leaders was (1945-2014), a chemist who established Mays Chemical Company in 1980. Mays grew his enterprise into one of the world’s largest chemical distributors and the 16th-largest African American industrial service company in the country. He used that success to help strengthen other Black businesses and support numerous philanthropic causes.

Mays was among the first African Americans to have a major civic impact outside of the Black community. He achieved several milestones, becoming the first African American chairman for the Greater Indianapolis and the first to chair the annual campaign for the . He was instrumental in the success of , an annual set of activities centered on a football game between historically Black colleges and universities. Launched in 1984, it became one of the city’s largest convention events and has brought tens of thousands of visitors to Indianapolis.

In 1991, Mays became the first Black chairman of the Indiana State Lottery Commission. He also contributed significantly to the growth of Black commerce in Indiana by investing in startup businesses, mentoring emerging entrepreneurs and advising organizations such as , the National Urban League, and the United Negro College Fund.

African American-owned businesses in Indianapolis grew steadily throughout the 1990s and into the early 2000s as the Black population increased to nearly 30 percent by 2010, or more than 326,000 residents.

Recent Growth and Challenges, 2007-

From 2007 to 2012, the number of Black-owned businesses in Indiana grew by 54 percent, according to the Census Bureau’s 2012 Survey of Business Owners (SBO). Indianapolis mirrored this increase, which occurred even as the country recovered from the Great Recession. However, most of these businesses were sole proprietorships without employees. More work was needed to grow Black enterprises, increase their share of the marketplace, and boost the number of government contracts.

In 2015, the Indy Black Chamber of Commerce (IBCC) was established to serve as an information resource for Black-owned businesses and enhance the economic status of the African American community. Since its formation, the chamber has offered mentoring, seminars, and networking opportunities designed to stimulate business development, growth, and success.

In recent years, more African Americans have achieved executive positions within established companies. Prominent examples include major Indianapolis utilities, with David Gadis becoming the first African American chief executive officer (CEO) and president of Veolia Water Indianapolis, and Jeff Harrison starting his tenure as president and CEO of Citizens Energy Group in 2015.

The global pandemic of 2020 had a significant impact on African American business owners. In March, Indiana joined other states in shutting down business activity as a result of the spread of COVID-19. This forced many businesses to close, and the decline was most severe among minority-owned enterprises. According to the IBCC 20 to 25 percent of African American businesses that were chamber members had closed due to COVID as of November 2020. In comparison, in June 2020 the National Bureau of Economic Research published a working paper by Robert Fairlie, a professor of economics at the University of California, Santa Cruz, that revealed that by April 2020 the number of operating African American-owned businesses fell nationally by 40 percent. The percentage that the IBCC reported, probably did not reflect an accurate number because it did not reveal closures of businesses that were not on its membership rosters. This fact may account for the discrepancy between local and national statistics.

In Indianapolis, approximately 200 African American businesses, IBCC members and nonmembers, applied for and received grants from the Indy chamber of commerce, with which the IBCC is not affiliated, to sustain themselves through the end of 2020. The Indy Chamber of Commerce received a $1.5 million city grant to deploy rapid-response loans and grants, as well as a $25 million grant toward Paycheck Protection Program loans deployable to small businesses. On the contrary, the 250-member IBCC applied for but did not receive city funding to grant its struggling business owners. Although the IBCC did not directly receive funding, the city noted that 18.3 percent of the rapid-response funds and 28.4 percent of the Paycheck Protection Program loans went to Black-owned businesses from the monies directed to the Indy Chamber.

During the summer of 2020, supporters of the growing Black Lives Matter movement for racial justice protested the deaths of unarmed African Americans at the hands of police. Advocates encouraged support for Black businesses as a way to help bridge the gap of income inequality and overcome what they viewed as decades of systemic racism.

The Indianapolis Urban League and Black business leaders such as communications executive Tamara Cypress, civic entrepreneur and columnist Marshawn Wolley, company owner Azia Ellis-Singleton and tech manager Bunmi Akintomide joined forces to promote African American enterprises. New Internet sites were introduced and social media tools like podcasts and online media blasts were used to help Black businesses recover from the pandemic and grow amidst sweeping changes. Networking groups such as Indy Black Millennials were created to connect African American professionals from various industries.

In June 2020, and the IBCC announced their strategic partnership to aid member businesses. WRTV’s commitment included highlighting Black-owned businesses through IBCC virtual events, featuring IBCC member businesses on Hiring Hoosiers, We’re Open Indy, and The Rebound: Indiana sections at wrtv-channel-6.com, and sharing news-related content. Online directories like IndyBlackOwned.com and ShopBlackIndy.com were introduced to help people find and support African American-owned businesses in Marion and surrounding counties. In July 2020, the Indy Black Businesses Matter marketing campaign was created to showcase African American businesses and help corporate partners achieve their diversity goals.

FURTHER READING

- Gibbs, Wilma L. “African American Businesses in Indianapolis, 1870-1950.” Black History News & Notes, no. 51 (February 1993): 4–7. https://images.indianahistory.org/digital/collection/p16797coll66/id/105/rec/14.

- Pierce, Richard B., ed. Polite Protest: The Political Economy of Race in Indianapolis, 1920-1970. Indiana University Press, 2010. https://search.worldcat.org/en/title/70704959.

CITE THIS ENTRY

APA:

Gibbs, W. L. and Perry, B. (2021). African Americans in Business. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Retrieved Mar 11, 2026, from https://indyencyclopedia.org/african-americans-in-business/.

MLA:

Gibbs, Wilma L. and Brandon Perry. “African Americans in Business.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021, https://indyencyclopedia.org/african-americans-in-business/. Accessed 11 Mar 2026.

Chicago:

Gibbs, Wilma L. and Brandon Perry. “African Americans in Business.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021. Accessed Mar 11, 2026. https://indyencyclopedia.org/african-americans-in-business/.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.