United States v. Board of School Commissioners of the City of Indianapolis, Indiana, was rooted in the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education that racial segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. However, it was not until a few days before the Indianapolis lawsuit was filed that the Supreme Court explicitly held that Brown not only prohibited segregation but affirmatively required integration. And it was not until the Indianapolis case had been pending for almost two years that the United States approved busing as a tool to achieve desegregation.

The Lawsuit and First Trial, 1968-1973

The lawsuit dramatically affected public elementary and secondary education in Marion County for nearly half a century. In the late 1960s, the U.S. Justice Department investigated alleged racist practices and policies within (IPS). On May 31, 1968, it filed suit against IPS for violating the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by deliberately “segregating minority (Negro) students from majority (white) students.” At the time and currently, IPS was not the only school district in Marion County. Each of eight , the City of , and the Town of maintained separate systems, but only IPS was the target of the Justice Department lawsuit.

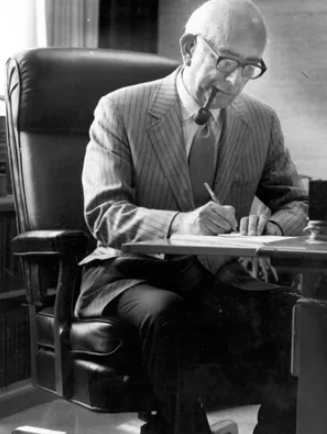

The case was assigned to Judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana. The court faced three issues. First, was IPS a dual school system, with Black students segregated from white students, or was it a “unitary” system? Second, if IPS was a dual system, did the racial imbalance result from unconstitutional de jure segregation (segregation from deliberate state action) or from constitutionally permitted de facto segregation (segregation unaided by any state action)? Third, if IPS was a dual system and the segregation was unconstitutional, what remedy should be ordered?

The trial occurred from July 12-21, 1971. On August 18, 1971, the court issued a lengthy decision holding IPS to be a dual, not unitary, system. The court further held that the “segregation was imposed and enforced by operation of law” and was, therefore, de jure and not de facto segregation. Evidence cited in the court’s decision included a lengthy list of historical state and locally enforced acts of racial discrimination, including racially motivated building and transfer policies, optional attendance zones, and school boundary changes adopted by the IPS board. From 1949 when legal segregation was officially ended in Indiana to 1968, school leaders had shifted the schools’ boundary lines 360 times, nearly all of which, the prosecution demonstrated, upheld a segregated system.

Other racially discriminatory practices cited were the construction of low-rent housing projects in locations that promoted racial segregation, and the State’s enactment of a metropolitan system of government popularly called , that consolidated the civil governments of the City of Indianapolis and Marion County but explicitly excluded consolidating public-school systems.

One consequential evidentiary finding was that “when the percentage of Negro pupils in a given school approaches 40, more or less, the white Exodus becomes accelerated and irreversible,” thereby leading to resegregation. The court called this phenomenon “the tipping factor” and resolved to devise a remedy for past segregation that would not cause white flight and resegregation. While the court did order IPS immediately to take certain action designed to lessen segregation within IPS, including the immediate desegregation of and all other single-race IPS schools, it withheld ordering a final remedy. Rather, the court directed the Justice Department to add the State of Indiana and the other public systems both in Marion County and in the surrounding counties as defendants, after which the court said it would proceed on the question of remedy.

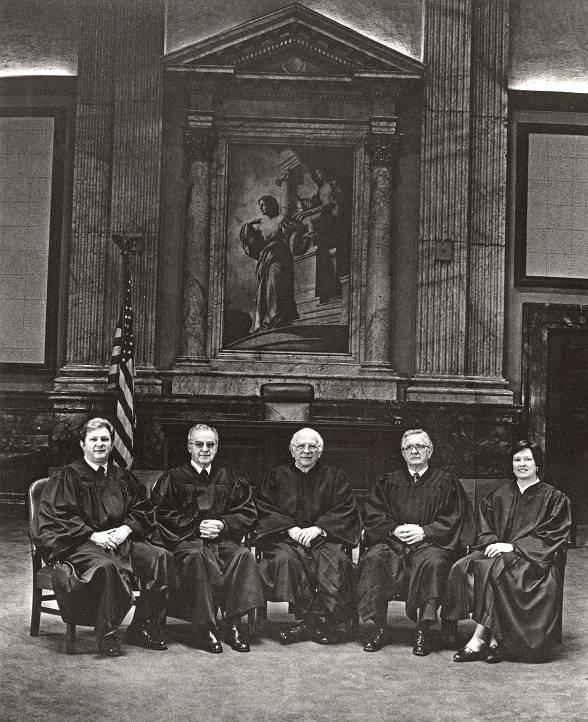

This decision was appealed. On February 1, 1973, the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit upheld the district court’s ruling in all respects.

The Second Trial and Appeal, 1973-1981

Following the decision of the circuit court, Judge Dillin resumed jurisdiction of the case with a significant expansion in the number of parties. First, a group of Indianapolis students were added as plaintiffs, lessening the Justice Department’s role. Second, the State of Indiana and 19 public school systems were added to IPS as defendants. These defendants consisted of eight township school districts in Marion County, the School City of Beech Grove, the School Town of Speedway, and nine school districts in counties adjacent to Marion County.

After a second trial, the court ruled on July 20, 1973, that the de jure segregation practiced by IPS was to be imputed to the State of Indiana. The court further concluded that the only feasible desegregation plan required the crossing of the boundary lines between IPS and nearby school districts and that the court had the power to do so because the state had been guilty of discrimination which had the effect of creating and maintaining racial segregation along school district lines.

The court said that if the Indiana General Assembly did not act to remedy IPS segregation during its upcoming session, the court would devise its own plan. As an interim measure, the court ordered IPS to immediately take steps to reduce the amount of segregation in its system. Most dramatically, the court held that while it had no jurisdiction to order the exchange of pupils between IPS and the other defendant school districts, it could require those districts to accept a reasonable number of Black students from IPS on a transfer basis. The court directed, with several exceptions, IPS to transfer to each of the defendant school districts a number of Black students equal to 5 percent of the total enrollment of each transferee school during the previous school year.

The legal reaction to this inter-district busing order was so intense that one close observer said it looked like the War in Vietnam. Judge Dillin became well-known for politely and patiently listening to irate citizens vent their feelings, and then calmly explaining the reasons for his decision.

This decision too was appealed. At the time of the district court’s decision, U.S. Supreme Court precedent authorized busing students to achieve racial balance as a permissible remedy for de jure segregation. But on July 25, 1974, the Supreme Court decided in Milliken v. Bradley that an inter-district remedy cannot be imposed for single-district de jure segregation without a finding that the other included districts had failed to operate unitary school systems or had committed acts of segregation.

On August 21, 1974, the circuit court upheld the district court’s conclusion that the state was responsible for IPS segregation but concluded that Milliken dictated that the busing remedy could not be applied to the districts outside Marion County. On the question of whether Milliken permitted busing to the non-IPS school districts within Marion County and included within Unigov, the circuit court remanded the case to the district court for further findings.

Following remand, Judge Dillin ruled on August 1, 1975, that Milliken did not prevent an inter-district remedy as to the non-IPS school districts inside Marion County because Unigov, in not expanding IPS boundaries along with civic boundaries, inhibited school desegregation. He found that the suburban units of Marion County had resisted civil annexation until Unigov had made it clear that schools would not be involved, and resisted public housing projects outside IPS territory, all of which caused the township districts (other than and ), Beech Grove, and Speedway, to be segregated white schools. The court enjoined any new public housing within the boundaries of IPS and ordering IPS to transfer Black students to the township districts (other than Washington Township and Pike Township), Beech Grove, and Speedway such that the total enrollment of pupils those school corporations would be approximately 15 percent Black. Washington and Pike Townships were excluded because they already had Black enrollments at or nearing that level.

On July 16, 1976, the circuit court affirmed Judge Dillin’s ruling that a Marion County-wide desegregation remedy was permissible under Milliken because Unigov’s limitation of the expansion of IPS constituted state action to avoid desegregation. The circuit court also affirmed the injunction prohibiting any new public housing within the boundaries of IPS.

Appeal and Reconsideration, 1977-1981

The circuit court’s decision was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. On January 25, 1977, the Supreme Court vacated the decision affirming the desegregation remedy and remanded the case to the circuit court for further consideration in light of the high court’s decisions in Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corporation (1977) and Washington v. Davis (1976). These cases, though not school desegregation cases, held that proof of racially discriminatory intent or purpose was necessary to make out a constitutional violation —not just proof of racially disproportionate impact.

On February 14, 1978, the circuit court vacated its earlier decision and remanded the case to the district court for further findings as to whether the General Assembly had acted with discriminatory intent or purpose when it restricted IPS boundaries while enacting Unigov. It also told the district court to determine what, if any, discriminatory state-responsible housing practices caused segregated residential patterns and to consider explicitly whether the scope of the district court’s remedy fit the nature of the constitutional violation.

On July 11, 1978, Judge Dillin responded, finding racially discriminatory intent to be “perfectly obvious” with respect to Unigov’s restriction of IPS boundaries and that the location of public housing within IPS was motivated to keep Blacks within IPS and the rest of Marion County “segregated for the use of whites only.” His finding estimated that the public housing practices deprived at least 7,000 pupils of a desegregated education.

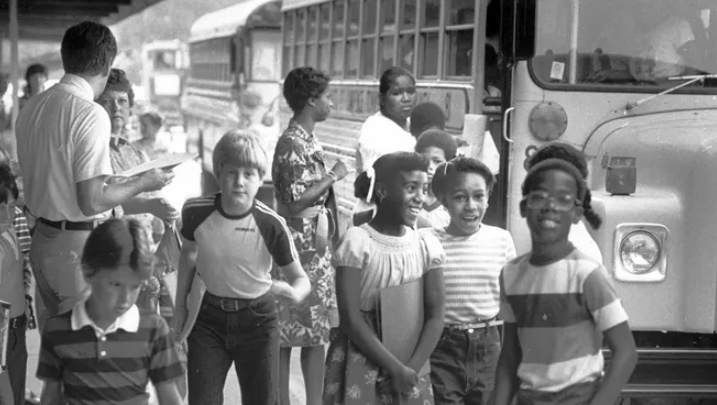

This decision too was appealed but the circuit court deferred consideration until the district court worked out additional details as to its remedy for the constitutional violations it had found. On July 9, 1979, after hearing alternate desegregation plans, the district court adopted what was called “Plan A.” This plan directed that an aggregate of approximately 6,125 Black students be transferred from IPS in specified numbers to the township districts (excluding Washington and Pike Townships), Beech Grove, and Speedway. It also provided ancillary relief such as mandated in-service training, and protected IPS teachers rendered surplus by the busing of IPS students.

On April 25, 1980, the circuit court reaffirmed the conclusions that Unigov’s limiting of IPS’s boundaries and the placement of all public housing with IPS boundaries supported the Marion County-wide desegregation remedy. The court also held that the district court had authority to order students transferred from the non-IPS defendant school districts as well as to them, contrary to Judge Dillin’s earlier conclusion. However, the court directed the district court to consider whether including Beech Grove and Speedway within the remedy was proper given the status of Beech Grove and Speedway within Unigov as “excluded” communities. (Judge Dillin subsequently removed Beech Grove and Speedway from its Marion County-wide desegregation order.) On October 6, 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear any further appeals.

On July 17, 1981, in response to a request from four township districts, the district court ruled that the State of Indiana should pay the entire cost of Marion County-wide desegregation because it alone had been found liable for the constitutional violations. The circuit court later affirmed this ruling.

Final Rulings, 1981-2016

During the two-week period beginning August 19, 1981, inter-district busing of approximately 5,500 Black students from IPS to the six township districts began. In addition, the start of the 1981 school year marked the completion of IPS’s internal desegregation efforts that had begun following Judge Dillin’s order in 1973. Whereas the vast majority of Black students attended all-Black schools when the lawsuit was filed in 1968, by 1981, no elementary school was more than 54 percent Black and all were at least 32 percent Black. The combination of busing and internal efforts caused or had caused the closing of 10 elementary schools and and the dismissal of 525 teachers.

In subsequent years, the district court was called upon to rule in several ancillary matters. In 1983, the court approved the award of $1.3 million in attorney fees to three attorneys for the Black student plaintiffs. The next year, the court ordered that parents of children bused to township districts be allowed to vote in and run for township school board elections. And in 1993, the court approved the IPS request to replace the intra-IPS busing plan with the Select Schools program. This program, implemented in fall 1993, allowed limited parental choice within IPS boundaries but maintained busing to the Township Districts.

In 1997, IPS asked the district court to terminate the desegregation order but the court declined. Shortly thereafter, the circuit court ordered the district court to allow IPS to present evidence as to why it believed the desegregation order should be terminated.

In June of the following year, a settlement agreement was filed with the district court proposing a phaseout of the busing of Black students from IPS to the six township districts. On June 25, 1998, Judge Dillin approved the settlement, providing a 13-year phaseout of busing beginning in 1999 for some township districts and in 2004 for others. His order continued State funding during the transition; an agreement to expand affordable housing choices throughout Marion County. It also declared that IPS had achieved status.

Busing of Black students from IPS to township districts came to an end in Indianapolis in 2016. Opinions on the effects of inter-district busing in Indianapolis differ. One article published at the end of busing in 2016 concluded that the students who were bused were provided better educational opportunities but the neighborhoods and schools from which they were bused suffered as a result.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.