Middle-class women in Progressive Era America (1890s to the 1920s) took active roles in reform initiatives to address society’s ills. In Indianapolis, these “Municipal Housekeepers” typically came from educated, well-to-do Black and white families. Though segregated, these women formed organizations to structure their work for the causes they supported.

Prominent women of Indianapolis’ Black community established the Woman’s Improvement Club (WIC) of Indianapolis in 1903. They first formed as an exclusive literary group with membership capped at 20 members. Some of these women were professionals themselves, while others were married to professional men. They included journalist , Ida Webb Bryant, , Rose D. Hummons, and physician and educator .

Fox, a journalist for the , was the group’s president and founder. Another leading member of the group, Porter Price, a former teacher and Indianapolis physician, was a principal in the system. Her medical training benefited the club when it expanded its activities into social efforts and community outreach.

Early members studied topics related to “racial pride and solidarity” and women’s issues. They read literature of African American writers, the poetry of Phyllis Wheatley, and learned about the lives of Black missionaries, evangelists, inventors, and social and political leaders.

These WIC clubwomen actively engaged with other local literary clubs, religious groups, and Black organizations that held gatherings in Indianapolis. These ties widened the club’s contact base and helped obtain support for WIC projects. Members sponsored educational lectures to fund these projects. Speakers included Mary Church Terrell, the first president of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, W. E. B. Du Bois, author of and magazine editor for the NAACP, and anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells.

The WIC soon expanded its initial work of educating the public on personal growth issues to its hallmark endeavor—health care for Black people afflicted with tuberculosis. In Indianapolis, public funds were allocated to combat tuberculosis, and private benevolent organizations spearheaded health care efforts. However, these funds and efforts dodged the afflicted African American community. In response, the WIC raised money to establish a fresh-air camp to serve the city’s African American population in 1905.

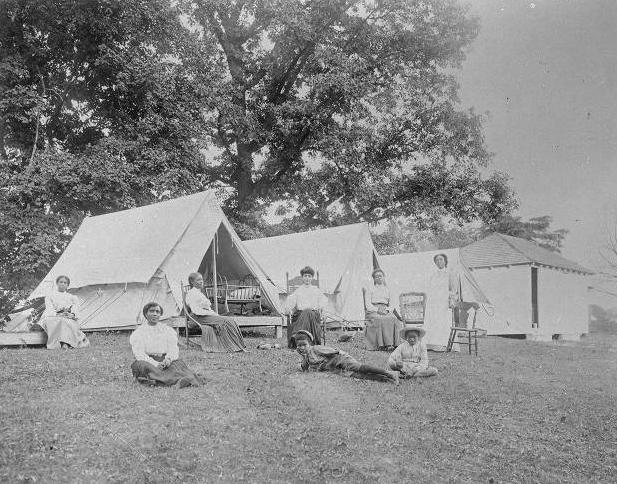

WIC members gained permission from William Haueisin, an Indianapolis businessman, to use his property in , a neighborhood adjacent to Martindale which was a residential center of the African American population, to establish the Oak Hill Camp. Without federal funding, the organization established what is believed to be the first fresh-air camp for tuberculosis patients in the United States.

Modest, with just three tents and operational only during the summer months, the camp functioned from 1905 to October 1916, treating six patients at a time. The volunteer-run camp remained afloat through the WIC’s fundraising campaigns, community donations, and WIC member contributions until its closure in October 1916. Local land development, lack of funding, and an emphasis on home-based care rather than institutional care for tubercular patients all led to the camp’s demise.

In the 1910s, the club admitted domestic workers, cooks, seamstresses, or household servants into its ranks. Membership passed from mother to daughter and continued to be limited to 20, which allowed the group to work together closely on projects. Between 1916 and 1918, WIC members continued to sponsor a lecture series to raise funds for tuberculosis patients. These lectures increased awareness about the disease and educated the Black population of other health concerns.

Indianapolis’ health care facilities continued to operate in a segregated fashion during the 1910s. The only facility in Marion County that provided care for African American tuberculosis patients was Sunnyside Sanitarium, which opened to the east of Indianapolis beyond Fort Benjamin Harrison in 1917. In 1918, it admitted only 19 Black patients. Public funds were not allocated to assist Black tuberculosis patients in the county until 1919. Despite these challenges and setbacks, the WIC continued its efforts to provide Blacks with tuberculosis care through involvement in year-round social work.

In one instance, the WIC worked with the city’s first fresh-air school for African American students at IPS Number 24, where was principal in 1916. In another case, the clubwomen persuaded leaders to change its discriminatory practices and establish a division at its Indianapolis plant staffed with African American women. The women hired WIC member Daisy Brabham in 1918 as the company’s first salaried visiting nurse/social worker.

In addition to its health care initiatives, the WIC supported the United States during World War I. It raised funds for the War Chest Board and contributed to the National Colored Soldiers Relief Committee and Colored Soldiers Comfort Home. Fundraising efforts also assisted the orphans of Black soldiers.

After the war, the WIC continued its crusade to provide health care for African Americans suffering from tuberculosis. At this time, the club’s membership again shifted to the educated ranks of teachers and social workers. Earlier efforts proved unsuccessful, but the WIC did convince the Indianapolis Hospital, a public tuberculosis facility attached to , to open a room for Black patients in 1918 and secured funding from the War Chest Board to help finance it. In 1919, the WIC successfully petitioned the Marion County commissioners to appropriate funds to care for Black tuberculosis patients at Sunnyside. The sanitarium’s reports, however, indicate the bed allotment for tuberculosis patients did not increase until 1926. Yet that allotment still dictated only 1 bed for every Black patient to 10 beds for every white patient in Marion County.

In 1922, to help compensate for the continued shortage of hospital beds for Black tuberculosis patients, the club began providing care at the Hospital, a facility that served the African American community starting in 1911. The club operated the tuberculosis unit there for two years before purchasing a home on Agnes Street in 1924. The Agnes Street Cottage had space to care for 6 patients at a time, about 35 patients per year. Later, in 1938, WIC members persuaded the city’s Flower Mission to establish a segregated wing at City Hospital to treat Black tuberculosis patients.

WIC expanded its social services in the 1920s. The clubwomen provided aid to indigent Blacks facing eviction and food to impoverished and underfed African American children in Indianapolis. The women also sent some of these children to summer camps in the country.

By 1960, medical advances reduced the threat of major health complications from tuberculosis. Although the club discontinued tuberculosis-related work, it continued to support the local African American community in other ways. The clubwomen paid a visiting nurse to provide advice to Black families and to help them get medical care and social services. The club also provided scholarships to students graduating from . By the mid-1960s, membership significantly declined. Though the organization continued to exist into the early 1980s, it remained inactive after its last regular meeting in December 1970. The remaining members donated their records to the in 1984.

While other benevolent groups stepped into Progressive Era reform related to health care, the Woman’s Improvement Club initiated the effort to provide tuberculosis care and facilities for Black patients in Indianapolis. Throughout its existence, the club provided health care to the city’s African American community, assisted its impoverished residents, and aided at-risk youth. While the club provided its members with opportunities for personal growth, educational improvement, and community service, its legacy remains in its hallmark Progressive Era scientific and professional approach to treating Black tuberculosis patients.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.