As the home of the state capital, as well as branches of local and federal governmental agencies, religion and politics have had nearly constant interaction throughout Indianapolis history.

Early Denominational Rivalry and the Civil War, 1820-1865

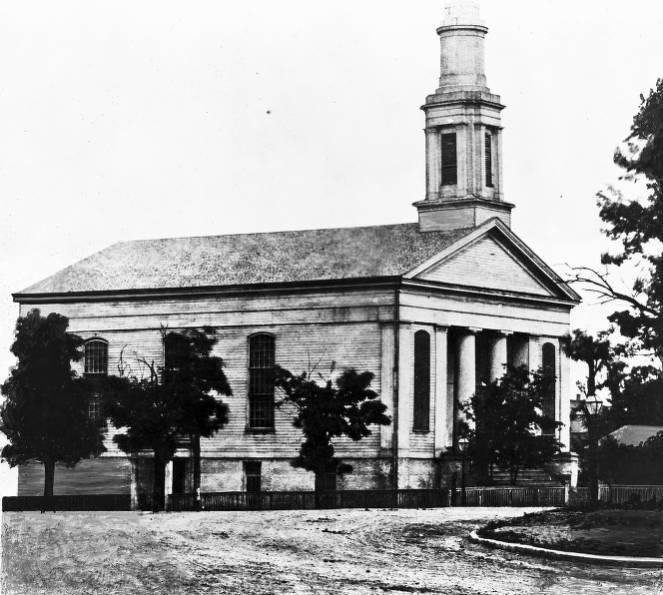

For much of the early 19th century, denominational rivalry between and drove most of this interaction. When remarks made by Whig candidate for governor, Samuel Bigger, came to light in 1840, in which he referred to the president of the Methodist college Indiana Asbury (now DePauw University) as “professor” instead of “reverend,” it became a political scandal. A few years later, another scandal between the two denominations erupted when former Indiana governor Noah Noble died. His funeral was to be held at Wesley Chapel, which he had recently joined. Some family members requested the participation of Reverend in the official service at the Methodist church. After the largest funeral that the city had yet seen, Indianapolis Methodists and Presbyterians argued over whether it was proper for the two congregational leaders to share a pulpit, even if briefly.

Other issues soon surpassed such denominational squabbles. Most, though not all, Hoosiers opposed slavery, and there were a growing number of abolitionists in the Circle City as the approached. In a May 1843 sermon delivered at Second Presbyterian, Beecher proclaimed slavery a moral evil facing the nation. He was far from alone in condemning the institution. Banned in Indiana (and the entire Midwest, thanks to the Northwest Territorial Ordinance of 1787), attitudes about slavery were hardening in both the North and the South. Increasingly, Protestant denominations (including the Methodists, , and Presbyterians) split over the issue and any sort of middle ground was disappearing. During the Civil War, two of the city’s churches— and —became victims of what their congregations believed to be “anti-abolitionist” violence because of their stances on the peculiar institution.

World War I and Anti-German Sentiment, 1914-1918

While other issues, from labor relations, reforms, immigration, and both anti-Catholicism and anti-Protestant sermons appeared in the city’s pulpits, the next major confluence of faith and state came during . Indianapolis’s congregations rallied to the war cause, via sermons, supporting soldiers, fundraisers for the YMCA and Red Cross, and even planting Liberty gardens. Some ministers, like Second Presbyterian’s Owen D. Odell and Frank Loveland, even left their congregations to devote themselves full time to the war effort. American congregations faced an additional challenge—how to handle not just anti-German sentiment caused by the war, but also anti-German language laws the state passed and debated that affected their worship services.

Temperance, Prohibition, and the Ku Klux Klan, 1920s-1930s

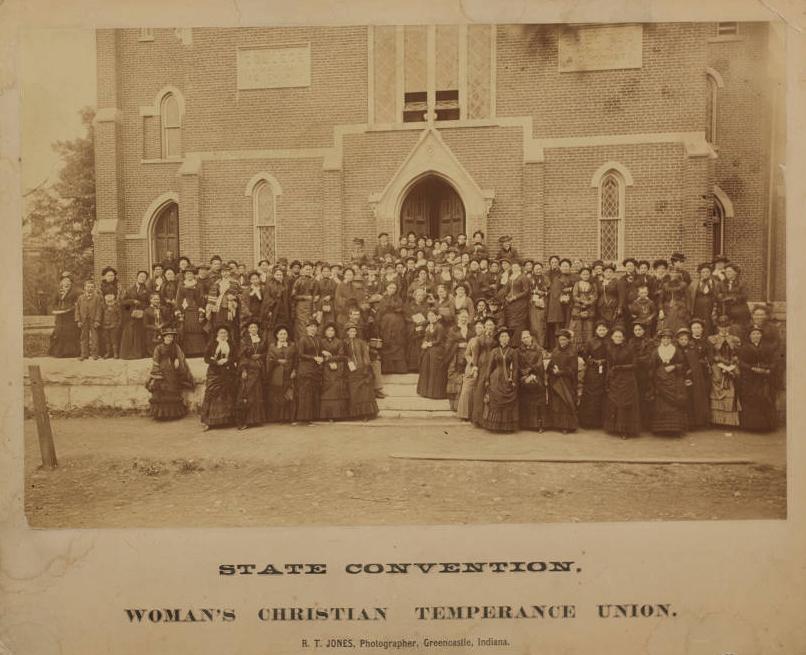

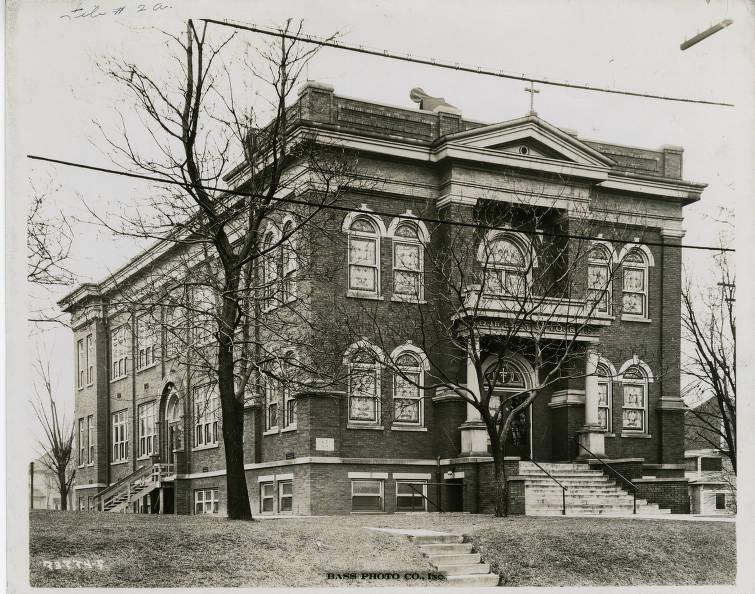

These wartime trends culminated in the greatest intersection of politics and faith of the 20th century: . Temperance reform of alcohol consumption had long been a part of Hoosier pulpits. By the late 19th century, para-church groups such as the (whose leader, Frances Willard was elected to the post in Indianapolis in 1879, also aligned the group in favor of women’s suffrage as a means to enact dry laws—a position many male drys also came to embrace) and the Anti-Saloon League both relied heavily on (almost exclusively) Protestant churches for their leadership and support. In the case of the League, a Methodist pastor, Reverend Edward S. Shumaker, led its Indiana chapter, detailed by his denomination for work with the organization. The League was perhaps the first political action committee in American politics, an interest group that operated at the local, state, and national levels, and whose motto was “the Church in action.”

Prohibition dominated the state’s political discourse for most of the first three decades of the 20th century, forcing politicians to take a stand, and eventually propelling Republican (and Methodist) governor into becoming the 1916 presidential nominee of the Prohibition Party. Being on the wrong side of the issue could also be devastating to political careers, as was the case in 1907 when Vice President hosted President Theodore Roosevelt at his Indianapolis home. During a civic celebration at Fairbanks’ home, the president asked for a cocktail. The staff informed him that the devout dry Fairbanks had no alcohol to serve. When someone procured a drink for the president, and the story spread, Fairbanks’ Methodist credentials were besmirched, with the scandal hurting his bid for the Republican nomination for president in 1908.

In the midst of the Prohibition era came another intermixing of politics and faith. In the early 1920s, the second manifestation of the arrived in the state. It was a fraternal society, a terrorist group, and political advocacy organization all rolled into one. Revived in the Jim Crow South in 1916, by the early 1920s it had spread to Indiana, where it was led by . Stephenson figured out that to make the Klan viable in Indiana he needed to repurpose messages most Hoosiers already embraced: support for Prohibition, 100 percent Americanism (aimed at immigrants who did not seem to be assimilating), and a variation of Protestant anti-Catholicism (see ).

Stephenson made the Hoosier Klan a family organization, garnering some one-third of all eligible Hoosiers as members, which made him wealthy and politically influential, as well as a rival to both denominational structures (as the Klan recruited heavily from within Protestant churches) and political parties (its members were both and —with both parties wary of alienating the Klan because of its “get out the vote” potential).

The Klan’s rapid rise came with an equally quick fall. Having portrayed the Klan as the protector of (Protestant) Christian values, Stephenson’s arrest and conviction for the murder of (coupled with an attempt by the Atlanta, Georgia-based national Klan leadership to take control of the Indiana Klan), spurred most Hoosiers to quit the Klan as quickly as they had joined it.

Suburbanization, UNIGOV, and Community Placemaking, 1945-2000

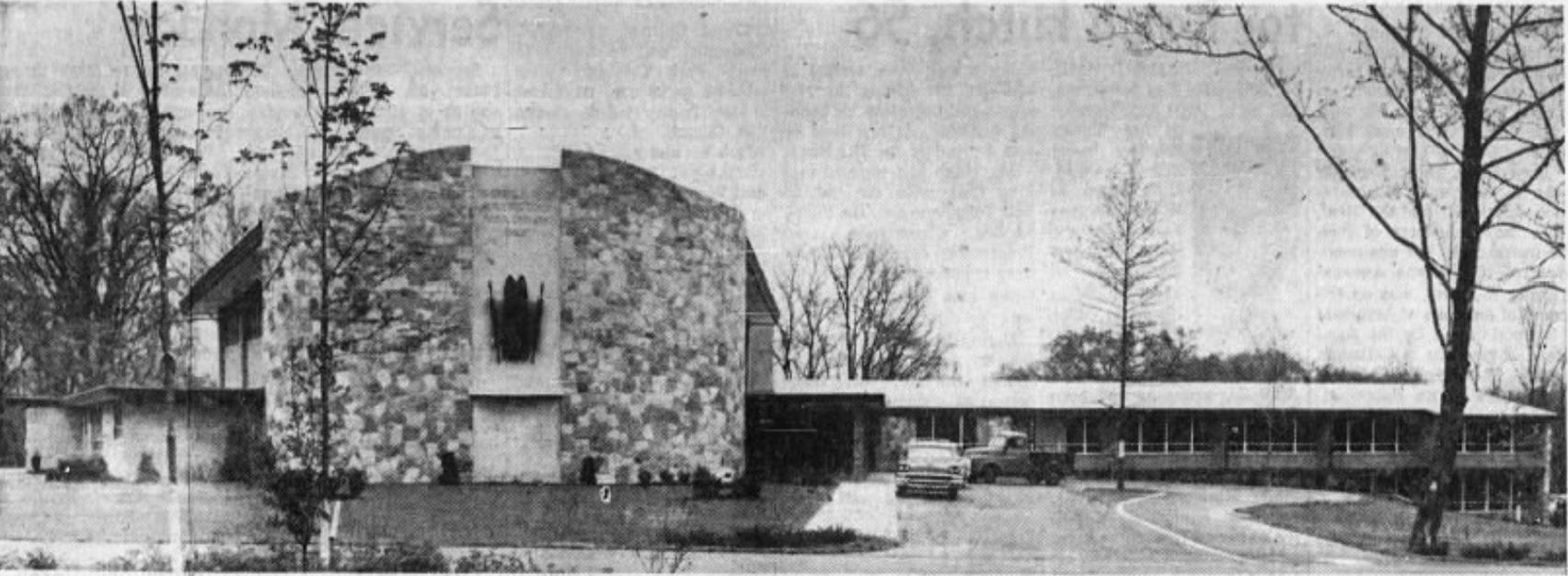

As issues like Prohibition and the Klan faded away, politics and faith once again became intertwined in the years after World War II as suburbanization (and the property issues that went along with it) came to the fore. Indianapolis congregations began moving out of the downtown area and into new residential areas. Area homeowners, who wanted to retain the feel of being outside the city while still living there, often met these relocations with hostility. In , for example, every congregation (Second Presbyterian, , the , 31st Street Baptist, and St. Luke’s Catholic Church) that attempted to move there faced opposition—including lawsuits. With the exception of the Baptists (who opted to relocate elsewhere), all the congregations eventually overcame the initial reluctance of Meridian Hills to embrace them.

Suburbanization continued to be a politically charged, religious issue in the city. Congregations had to decide whether to stay or move, adapt to changing neighborhoods, expand social service offerings, and pay for upkeep on aging buildings as their membership declined. Some remained, others merged, and some disappeared, with their buildings turned into parking lots and new construction. Suburbanization also left the city core a virtual ghost town. Under Mayor leadership, the city launched , which consolidated the city and most of the county-level governmental structures. Lugar did so, in part, by utilizing religious imagery, including the Christian imagery of rebirth.

An actual minister, , who left the pulpit of Second Presbyterian Church to enter politics, followed Lugar into office. , who became mayor after Hudnut, focused not just on large-scale construction projects but also on the city’s neighborhoods. To do so, he enlisted religious congregations and organizations in his Front Porch Alliance to help with specific problems, in specific areas, with specific programs—all while fostering a sense of community in the wake of nearly 30 years of changes.

The Indiana Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), 2015

The 21st century saw the city become the epicenter for a battle over Indiana’s version of the . As momentum began building towards the legalization of same-sex marriage (confirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision in June 2015), then-Governor Mike Pence pushed for RFRA. Brought through the state legislature with little fanfare in March 2015, Pence signed RFRA into law in a private ceremony attended by conservative religious leaders. Critics, who claimed it would promote discrimination against the LBGTQ+ community, and business leaders, who worried it would cast Indiana in a poor light, quickly attacked the new law. Pence agreed to have the language of the law changed, which quieted the protest but upset many of the original bill’s supporters.

The discussion of religious liberty prompted by RFRA took an interesting turn when local Libertarian Bill Levin announced that Indianapolis would become the home to a new congregation that he founded: the First Church of Cannabis. The new church was more than just a religious veneer for a movement to try and get Indiana to legalize marijuana. While the congregation found protection under RFRA in the courts, by 2019, it also could not get legal approval to use cannabis for religious purposes.

Whatever the future holds, Indianapolis is sure to see more interplay between faith and politics.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.