The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, part of the Compromise of 1850, amended the 1793 Fugitive Slave Law by giving the federal government sole jurisdiction over cases of fugitive enslaved persons. Following a summary hearing, special commissioners could issue warrants for the arrest of fugitives and certify their return to their masters. An affidavit by the claimant was accepted as sufficient proof of ownership. To entice commissioners to return suspected fugitives, commissioners received $10 for each return certificate and half as much if return was denied.

Fugitives claiming to be free men were not entitled to a jury trial and could not testify on their own behalf. Likewise, those who interfered with the law were penalized. Marshals refusing to execute warrants were fined $1,000 and citizens interfering with the arrest of a suspect were fined $1,000, with a possible six-month jail term.

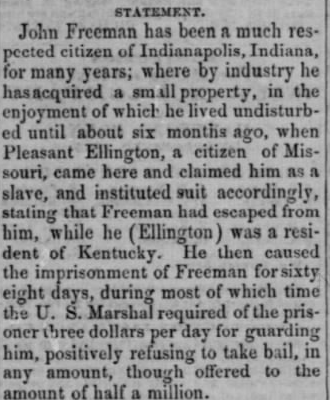

A native of Georgia, John Freeman came to Indianapolis about 1844, where he was a painter and owned a restaurant. On June 20, 1853, United States marshals arrested him on an affidavit sworn by Reverend Pleasant Ellington, a Methodist minister from St. Louis, Missouri. Ellington claimed that 17 years earlier, while a resident of Kentucky, his slave Sam ran away, and alleged that Freeman was in fact Sam.

Hearing of Freeman’s predicament, Indianapolis attorneys John L. Ketcham, Lucian Barbour, and came to his aid. The attorneys successfully petitioned the U.S. commissioner for additional time to prepare their case but lost their request that Freeman be released on bond during that time.

Freeman’s lawyers found witnesses in Georgia who were prepared to testify that Freeman had lived in Georgia as a free man from 1831 to 1844. The lawyers also located the real Sam residing in Canada under the alias of William McConnell, but understandably he refused to return to Indianapolis for the trial.

Witnesses who met Sam testified that his physical characteristics did not resemble Freeman’s. For his part, Ellington produced three witnesses who, after stripping Freeman to examine his body, claimed he was Sam. The case was dismissed when Ellington’s son could not identify Freeman.

Released from jail after nine weeks, Freeman retained his freedom but lost his savings in the process. He brought a civil suit against both Ellington and the arresting federal marshal, John L. Robinson. Freeman sued Ellington for $10,000; the court ruled in Freeman’s favor, but reduced the award to $2,000. Ellington, however, had fled Indianapolis, leaving no means to collect the settlement.

Freeman also brought suit in the Marion County Circuit Court against Robinson for $3,000, charging him with assault, forcing the prisoner to strip, and extorting $3 per day for protection while imprisoned. The Indiana Supreme Court agreed in December 1855 that Robinson had acted improperly but dismissed the case because it had been filed in Marion County instead of Rush County where Robinson resided.

Freeman sold much of his property to pay his debts and when the Civil War began, he moved his family to Canada.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.