The Walker Building was erected in 1927, eight years after the death of , founder of the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. The anchor of a thriving Black business and residential community, it served as the hair care enterprise’s headquarters for five decades. Since 1984, the building has been a cultural center and performing arts venue now known as the Madam Walker Legacy Center.

Madam Walker, who was born Sarah Breedlove in Delta, Louisiana, in 1867, moved to Indianapolis in 1910 four years after establishing the Walker Company in Denver, Colorado. She began purchasing the triangular-shaped parcel of land in 1916 to expand the factory she had opened behind her residence at 640 N. West Street (now Martin Luther King, Jr. Street) the year she arrived in the Hoosier capital. After her death in 1919, Walker Company’s general manager and attorney completed the acquisition of the land and began overseeing construction of the building in partnership with Walker’s daughter, A’Lelia Walker, who managed the company’s Harlem office.

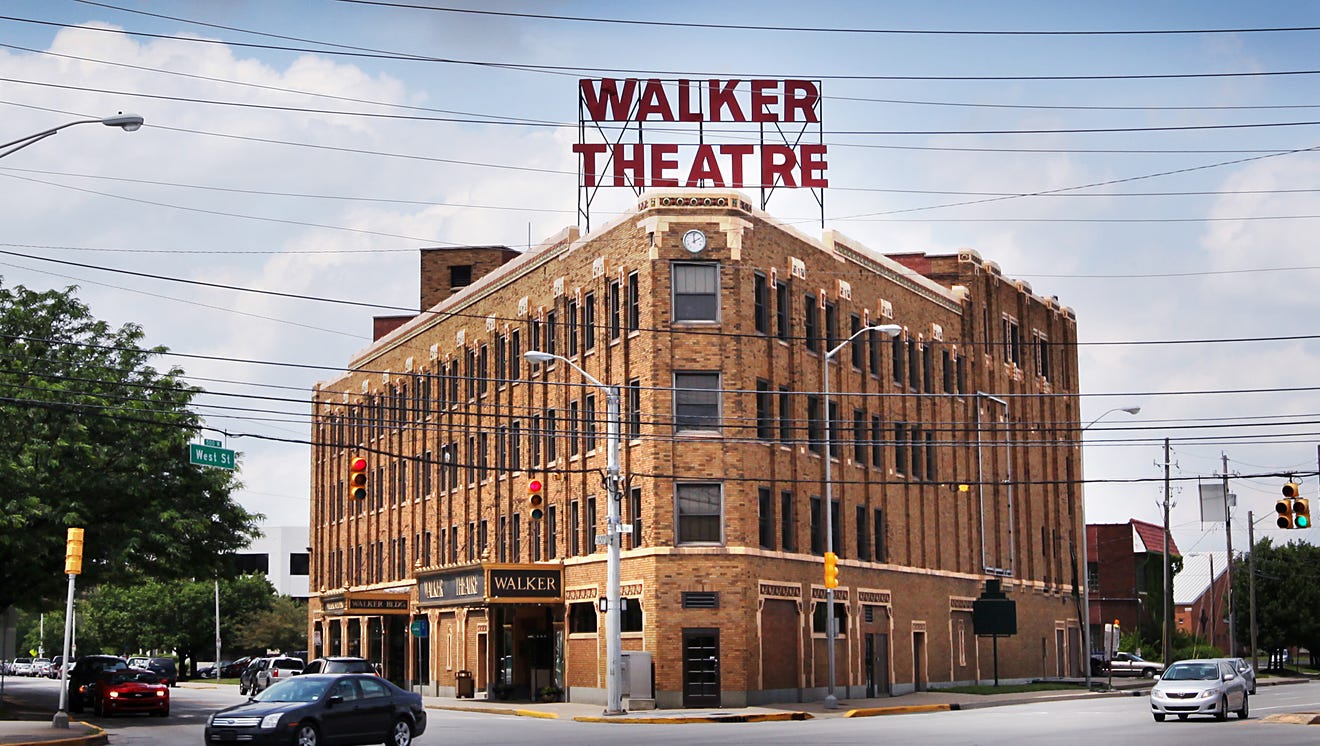

Designed by Indianapolis architectural firm , this four-story flatiron structure sits at the intersection of and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Street just outside the northwest corner of the . When the doors opened in December 1927, the Walker Building was called “a city within a city” because of the range of services it offered. In addition to the Walker factory and corporate offices, the structure included a pharmacy, beauty salon, barbershop, cosmetology school, restaurant, medical offices, ballroom, and 1500-seat theater. Theodore Cable, one of the first Black graduates of Indiana University’s School of Dentistry and a member of Indianapolis’s City Council, was a tenant.

The exterior of the 48,000 square foot, steel, and reinforced concrete structure includes a brick façade with terra cotta trim designed by Alexander Sangernebo, a master sculptor for the American Terra Cotta and Ceramic Company. The interior of the art deco theater features dozens of Egyptian, Moorish, and West African-inspired woodcarvings and plaster molds of masks, sphinxes, elephants, spears, and tribal symbols. Restoration artists who examined the original motifs during the 1980s discovered 110 shades of color on ceiling medallions, friezes, and door frames in the lobby and on the balcony and stage.

Ironically, the late 1920s construction boom that added the Walker Building, , and the to the cluster of existing buildings that served African Americans on Indianapolis’s near northwest side, was in part a by-product of racial segregation in public facilities that were approved by city leaders when members of the controlled Indianapolis local government from 1921 to 1928.

During its heyday from the 1930s through the 1960s, the Walker Theatre hosted first-run Hollywood movies and vaudeville shows as well as performances from nationally known singers Mamie Smith and Dinah Washington to homegrown jazz greats , , and . The Walker Casino ballroom was a popular venue for wedding receptions, graduations, fashion shows, fraternity dances, sorority galas, and debutante balls hosted by Black organizations.

By the late 1950s, Indiana Avenue—like the commercial arteries of inner-city Black communities across the nation— was in decline because of “redlining,” the racially discriminatory federal housing policies and banking practices that intentionally steered investment away from communities of color. The Marion County Metropolitan Planning Department’s 1958 Central Business District report labeled the area as “blighted” and designated it suitable for “slum clearance” in its master plan for the future development of a revitalized downtown. Black homeowners were offered less than market value for their residences and Black and Jewish-owned neighborhood businesses were forced to close to make way for the construction of I-65 and the expansion of the (IUPUI) campus and the .

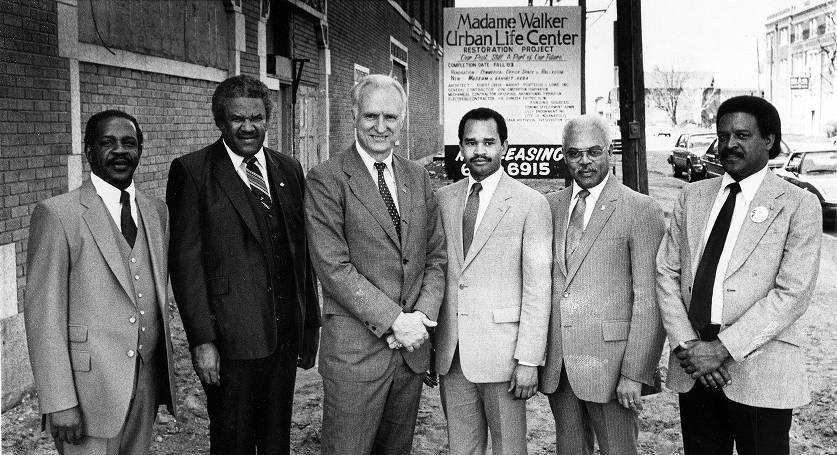

As neighborhood structures were razed, the Walker Building, too, lost tenants and began to decline. In 1979 the Madam Walker Urban Life Center, a not-for-profit organization, was formed by a group of concerned citizens to save the historic building from demolition. The building was added to the Indiana Register of Historic Places that same year and to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

Board directors commissioned Robert LaRue, an architect with to create a restoration plan that later included designs for the theater by and Alpha Blackburn of Blackburn Associates. After extensive renovation—supported by the and U. S. Commerce Department funding—the building reopened in 1984 and the Walker Theatre reopened in October 1988. It was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1991 and is one of the few physical reminders of Indiana Avenue’s role as the hub of the city’s Black cultural, commercial, religious, and civic life during the early twentieth century.

For the next 30 years, the Walker Center offered arts education and programming produced by the , , and the Metropolitan Youth Orchestra as well as signature programs like Jazz on the Avenue and Blues and Barbecue. Tap dancer Savion Glover, jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, dramatic opera soprano Angela Brown and singers Smokey Robinson, Michael Bolton, and Patti LaBelle were among the artists who appeared on the Walker stage during the 1990s and early 2000s.

From 1996 to 2017, the building was known as the Madam Walker Theatre Center. In 2018, the organization became known as the Madam Walker Legacy Center and entered into a partnership with IUPUI that now includes jointly sponsored programming, building maintenance, and offices for IUPUI’s Center for Africana Studies and Culture. The Asante Art Institute is a building tenant, and the center also partners with Freetown Village.

Lilly Endowment funded a $15.3 million renovation. These renovations included new light strips, expanded wheelchair access, and a new curtain for the stage. The renovation made way for a new sound booth and a flexible space in front of the stage. Other changes provided easier access to restrooms and a new roomy elevator. A new HVAC system was installed, the roof was repaired, and the iconic “Walker Theatre” sign was reconstructed to look like the old one but with more durable materials.

In February 2020, the announced plans in 2021 to extend its linear bike and pedestrian path into the 600 block of Indiana Avenue to include the entrance to the Walker Theatre. The expansion acknowledges the symbolic role the Walker Building has played for the last century in the life of Indianapolis and for the city’s African American community.

Reopening of the Legacy Center was delayed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although it hosted several open houses in fall 2021, the official grand reopening party will occur Juneteenth weekend in 2022.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.