Although Indiana’s 1816 constitution required the General Assembly to provide for a system of free public schools, equally open to all children, the framers were also realists, and added the qualifier “as soon as circumstances will permit.” In the earliest years of Indiana statehood the General Assembly passed laws authorizing the establishment of an elementary district school in each township and a secondary seminary in each county. State lawmakers failed to provide a source of adequate or stable funding for either. As a result, more than 30 years would elapse after the founding of Indianapolis in 1821 before the city’s first system of common schools opened to all children, free of charge.

Early Indianapolis schools

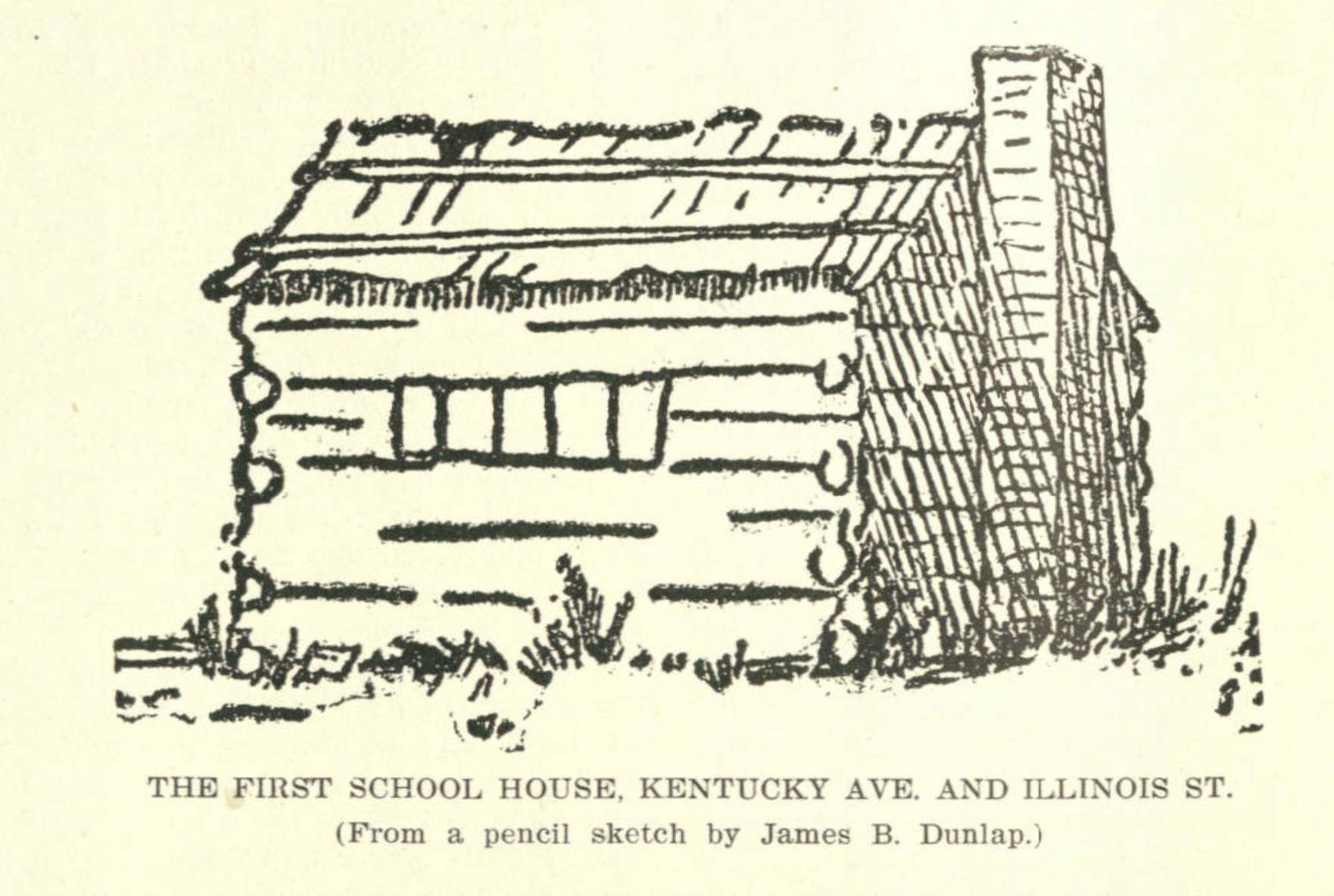

In the spring of 1821 fifteen settler families in the area the Indiana State Legislature established as the new state capital built a 20-foot-square log cabin at the current-day intersection of Kentucky and Washington streets. An eight-foot fireplace stood on one wall and greased paper covered the only window on the opposite wall. This structure served as a meeting house, house of worship, and first school for the settlers’ children.

In October of 1821, Joseph C. Reed opened the first pay school in the pioneer settlement of Indianapolis. Reed hoped to draw the children of incoming land speculators to this school, however, the expected “boom” of speculators failed to materialize. Those students who attended the school paid tuition, yet attendance was sporadic at best during the grueling winter months. The fledgling school was shuttered in April 1822 when Reed was elected county recorder, and for the next 12 years, the education of children in the new state capital fell largely to the church-run Sabbath Schools and a handful of secular day schools that charged varying rates of tuition.

The city’s earliest efforts to establish public schools centered around a provision in the 1816 Indiana constitution that directed penal fines and other fees toward a county seminary fund. Under an 1824 law, the funds were held by a trustee until the balance reached $100, at which point the voters were then authorized to elect a board of trustees charged with erecting a school building. Indianapolis hit the $100 benchmark in 1832, and , John S. Hall, and William Gladden were elected trustees.

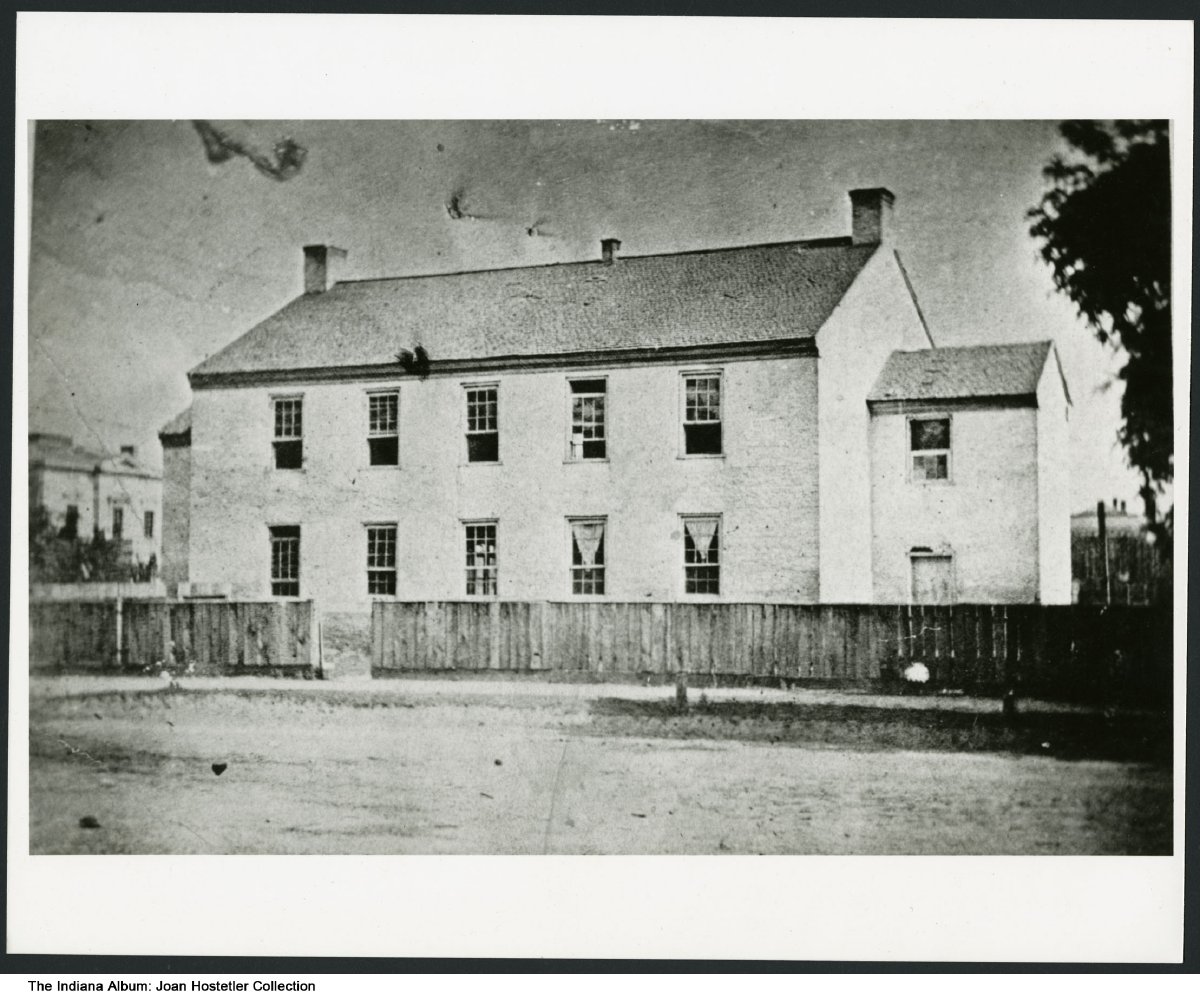

The newly constructed Marion County Seminary opened on September 1, 1834, in the southwest corner of University Park. Although the seminary was the first publicly operated school in Indianapolis, it was not free of charge. Nor was it open to all, as co-education was viewed with disfavor in pioneer-era Indianapolis. However, on the same day that the seminary opened its doors to male students, Miss Hooker’s Female School began offering classes to girls in reading, writing, and arithmetic, the “3 Rs,” along with lessons in needlework, drawing, history, and the use of maps. As Indianapolis grew over the next decade, a number of other private schools were established to serve the children of Indianapolis whose parents could afford to pay tuition and fees.

The Common School Movement

In 1841, the General Assembly enacted legislation that allowed a property tax to be levied to operate schools if approved by two-thirds of the householders. Three years later, the first district school opened in Indianapolis on the east side of West Street, just south of Michigan, following a bitterly contested referendum that passed by a single vote. Tuition was $3 per pupil for 13 weeks of instruction, but because public funds were used for the building, any student could attend regardless of ability to pay.

Despite the controversy over the referendum, support for free public schools was beginning to grow in Indiana. Caleb Mills, an influential educator and progressive thinker who is generally recognized as the “Father of Common Schools in Indiana,” penned a series of addresses to the legislature in 1846 that urged state lawmakers to provide for a system of free public schools that would be open to all children. Mills’ remarkable essays helped convince Hoosiers that one of government’s key functions was to provide a means for supplying a free education.

During the 1846-1847 General Assembly, Mills’ writings proved instrumental in convincing legislators to adopt a “free public school” provision in the first Indianapolis city charter, which transitioned Indianapolis from a town to city. The new charter included language that would provide for a property tax levy of 12 ½ cents “for the organization of a non-sectarian school system open to all and free from the taint of charity and pauperism.” This required all of the city’s districts to provide schools similar to the one that opened on West Street in 1844.

In order to secure enough votes for passage of the charter, an amendment was added that required voters to approve any tax levy for the support of public schools. Following a heated campaign, the free school supporters won by an overwhelming margin in 1848. This election laid the cornerstone for the Indianapolis public schools. But another five years would pass before the schools were actually free because the meager revenue generated by the tax levy was not sufficient to pay for both buildings and teachers.

By 1851, the school system had managed to scrape together enough funding for five small buildings in which two men and three women taught. The teachers did not receive salaries, however; their limited compensation was paid by patrons of the schools. There was no prescribed course of instruction, no general textbooks, no cooperation between teachers, and no superintendent or other centralized leadership. Instead, the schools were managed by seven trustees, one for each district.

Despite the shortcomings of the city’s first free schools, the movement was picking up steam. The new state constitution adopted in 1851 required the General Assembly “to provide by law, for a general and uniform system of Common Schools, wherein tuition shall without charge, and equally open to all.” The following year, legislation was enacted that granted cities the authority to establish school systems and levy taxes to pay for teacher salaries.

Indianapolis Public Schools

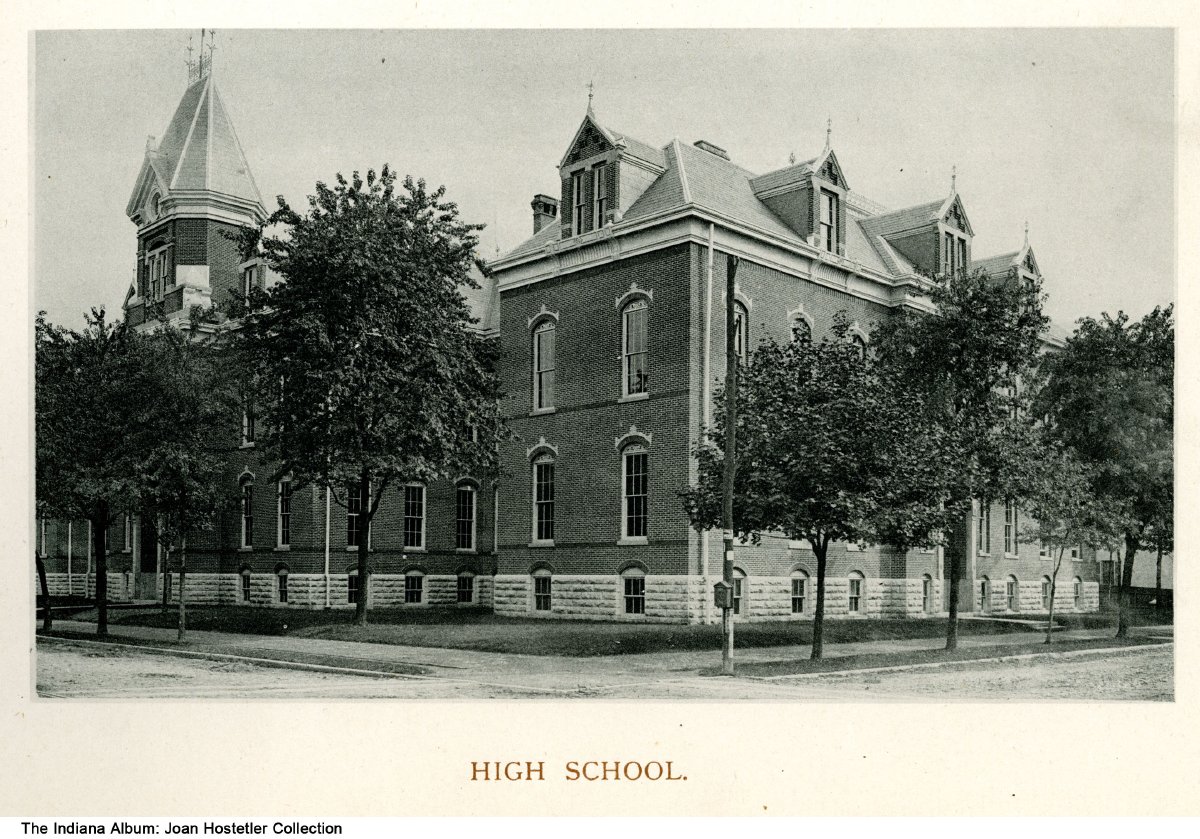

With a stable source of funding secured, the Indianapolis City Council appointed Henry P. Coburn, , and as trustees to organize and manage a new city-wide school district. The first seven elementary buildings in the new Indianapolis Public Schools (IPS) opened their doors on April 25, 1853, and continued in session for two months. A graded system was adopted in August 1853, and on September 1, 1853, Indianapolis High School (later renamed ) opened in the old county seminary building in .

During the Indianapolis Public Schools’ first term in 1853, classes were held in seven rudimentary district schoolhouses and lasted eight weeks. There was no uniform course of instruction, so the board of trustees looked to the private schools for guidance. But despite its humble beginnings, the newly established IPS system was a vast improvement over the patchwork assortment of “pay” schools that served a small portion of the city’s children during the pioneer era.

IPS flourished for the next few years. Students flocked to the new “free” schools, and the average attendance jumped from 340 in April 1853 to 700 in May. By 1857, the schools were in session for 39 weeks, with an average attendance of 1,800 students.

But this progress came to an abrupt halt in 1858 when the Indiana Supreme Court banned the use of local property taxes to pay for public school tuition. The meager amount of funding flowing from the state — approximately $2 per pupil—was insufficient to keep the schools open, so the entire IPS system was shut down in 1859. School buildings were rented out to former teachers who reopened them as private schools. In each of the next two years, the district was only able to scrape together enough money to provide a small number of students with 18 free weeks of education. No attempt was made, however, to reopen the high school.

The legislature increased the statewide property tax by 60 percent in 1861, which generated enough funding for IPS to provide a free term of 22 weeks for nearly 2,400 students in 1862. The following year, educator was selected to serve as superintendent of IPS. As a result of the systems and improvements he put in place during his tenure at the helm of IPS, Shortridge is widely regarded as “the father of the Indianapolis Public Schools.”

One of Shortridge’s first actions was to hire a promising young teacher, , to take charge of the primary grades, a post she would hold for the next 40 years. He then turned his attention to reopening the high school.

The Indianapolis High School reopened in September 1864 in the old First Ward School on the corner of Vermont and New Jersey. William Bell, the sole male teacher in the IPS system, was named principal. Unfortunately, none of the 28 pupils were found to be ready to pursue high school education, so a year of remediation was required before high school instruction began. Five students–four boys and a girl–comprised the first graduating class in 1869.

During Abraham Shortridge’s 11 years as superintendent, enrollment in the Indianapolis Public Schools increased ten-fold while the number of students attending private schools dropped by nearly 50 percent. Further, almost 10 percent of the children attending IPS were Black, a remarkable change from the bleak years immediately following the Civil War, when state law prohibited public schools from providing free public education to Black children.

Both Shortridge and the IPS board strongly believed a high-quality public education should be available to all students, regardless of race. Shortridge worked for a change in state law that would allow IPS to open its doors to Black students. In May 1869, in a special session of the legislature, an act was passed providing for separate public schools for Black children. By September, IPS had rented buildings, hired teachers, and was ready to serve all Black children who applied.

Within a couple of years, several Black children had advanced enough in their education to take high school level classes. However, the law required separate schools for Black and white children, and a high school for fewer than a dozen children was not feasible. A committee of Black community leaders approached Shortridge in 1872 with the idea of bringing a lawsuit to allow white-only high schools to serve Black children if a separate school was not available. Shortridge suggested that a better plan would be for IPS to just go ahead and admit a Black student to the Indianapolis High School and challenge anyone to object.

Mary Alice Rann showed up at IPS on the first day of school in 1872 and expressed a wish to enter high school. Shortridge walked her to the principal’s office and without any explanation or request said, “Mr. Brown, here is a student who wishes to enter high school.” Rann attended the high school for four years and became the first of many Black children to graduate from Indianapolis High School before opened in 1927.

After Abraham Shortridge retired from IPS in 1873 to assume the presidency of Purdue University, the educational progress achieved under his leadership continued for the remainder of the 19th century. Health education was introduced in 1880, opened in 1895, and enrollment swelled after passage of a compulsory attendance law in 1897 that required all children ages 8-14 to attend school. By 1900, IPS had 54 well-equipped school buildings and 544 teachers.

Early 20th-century growth and change

IPS entered the 20th century with a recognition that the role of women in society was changing. One of the first orders of business in 1900 was the adoption by the school board of a resolution that allowed female teachers to marry without forfeiting their jobs. But the district’s actions on racial integration remained firmly rooted in the previous century.

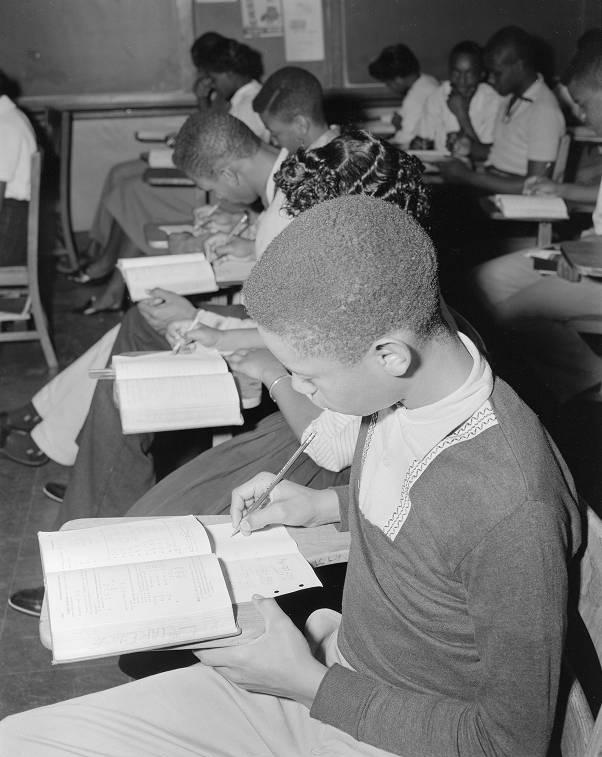

The system of segregated elementary schools that Abraham Shortridge started in 1869 continued through the first half of the 20th century, and grew with the city. By 1926, there were 15 elementary schools designated as “colored”–Schools # 4, 17, 19, 23, 24, 26, 37, 40, 42, 56, 63, 64, 65, 79 and 83. But the high schools remained integrated until 1927, when Crispus Attucks High School opened.

The was a powerful force in Indiana politics during the early 1920s, and influenced both IPS school board elections and the direction of the district. In 1922, the IPS board voted unanimously to open a new segregated high school over the strenuous objections of local Black leaders, who feared the new school would lack the amenities of the other IPS high schools. Their concerns were justified. When it opened in 1927, Attucks lacked a gym and was furnished with hand-me-down desks from other schools. But the all-Black faculty was first-rate, and over the years the school became a source of pride in the African American community despite the circumstances surrounding its creation.

IPS opened two other high schools in the early years of the 20th century to serve the city’s burgeoning population— in 1913 and George Washington High School in 1927. In addition, Broad Ripple High School was annexed by IPS in 1923.

From the mid-1930s through the start of World War II, enrollment in IPS remained relatively stable, hovering around 57,000 students per year. Following a slight dip during the war years, enrollment in IPS began to grow exponentially, reaching a peak of 108,743 students in the 1967-1968 school year.

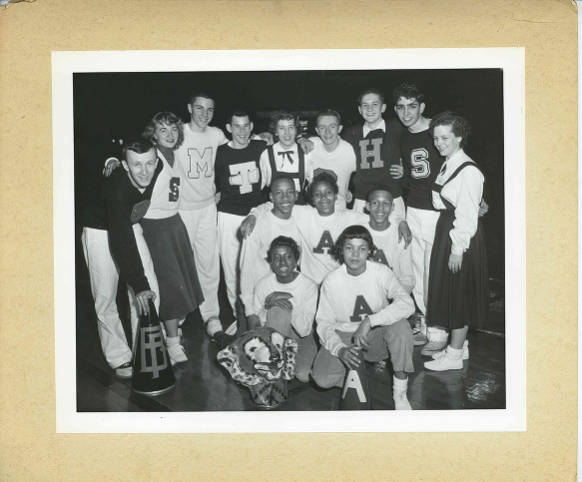

Three new high schools were opened by IPS to accommodate the enrollment explosion—Arlington High School in 1961, Northwest High School in 1962, and John Marshall High School in 1968. By the 1967-1968 school year, IPS had 11 high schools and 107 elementary schools. Most were built during the postwar population boom. But suddenly the bottom dropped out.

Midcentury enrollment decline

In May 1968, the U.S. Justice Department filed suit against the IPS Board of School Commissioners to force . Three years late, U.S. District Court Judge found IPS guilty of de jure segregation. The court demanded that IPS reassign staff and faculty, revise transfer policies, and negotiate with suburban school corporations for the transfer of minority students. It concluded that had fostered segregation by expanding the city limits to encompass the predominantly white surrounding townships and excluding the increasingly Black Indianapolis School district from that expansion. Dillin sought to include the outlying school corporations in the court’s proposed solution.

The case dragged through the federal courts for several more years. Attorneys for Black students argued for the adoption of an inter-district of unified school plan. Although the state of Indiana denied responsibility for perpetuating segregation in IPS, Judge Dillin ruled that the state possessed control over local school districts and had approved three new high schools at the outer limits of IPS, all without African American Students. Dillin concluded that a lasting remedy should include the suburban school districts in and outside Marion County and ordered one-way busing of Black IPS students to 19 other school districts in Marion and six neighboring counties. IPS was to absorb all expenses. Dillin’s cross-county-busing order was reversed on appeal, but his order to bus students to suburban school districts in Marion County was affirmed. In 1981—10 years after Dillin’s original decision—the busing of nearly 7,000 Black students from IPS to schools in Perry, Wayne, Franklin, Decatur, Lawrence, and Warren townships began.

As the worked its way through the courts, the number of students attending IPS plummeted sharply. During the 1981-1982 school year, 57,269 students were enrolled in IPS, a nearly 50 percent decline from the district’s peak enrollment 13 years earlier. Enrollment continued to decline during the 1980s. By the 2000-2001 school year, IPS’s enrollment stood at 41,108.

A number of different factors contributed to this enrollment decline. Starting in the late 1960s, many white families fled to the suburbs or enrolled their children in predominately white private schools. A number of Black families also moved outside the district, concerned about their children traveling long distances on a bus to attend schools far away from their neighborhoods. At the same time, the construction of the I-65/I-70 inner loop decimated many inner-city neighborhoods where IPS students lived, forcing their families to relocate.

As enrollment declined, the IPS board was faced with the difficult decision to close schools and redraw the boundaries for neighborhood schools. Between 1968 and 2000, IPS closed 51 school buildings, displacing thousands of children. Ironically, the school closures necessitated by declining enrollment also worsened the problem, as many families opted to leave the district when their neighborhood school was shuttered.

Late 20th-century reform

The late 1980s ushered in a new era of school accountability following the 1987 adoption of Gov. Robert D. Orr’s education reform plan, dubbed the “A+ Program for Educational Excellence.” One key component of the program was a statewide standardized test that would measure student progress and allow policymakers, parents, and the general public to compare results across school districts. The Indiana Statewide Testing for Educational Progress (ISTEP) got underway in 1988, and IPS’s results were abysmal. The district ranked second to the bottom in overall pass rates, trailed only by schools in East Chicago. After several years passed with scant improvement, state and local leaders began calling for reform of the system.

In 1992, the IPS Board approved a sweeping reform plan that would trim central office bureaucracy, give teachers and principals more control over decision-making, and implement school choice within IPS. Dubbed “Select Schools,” the school choice plan aimed to engage parents and improve academic achievement by fostering competition for students among IPS schools. Select Schools went into effect in the fall of 1993 following approval of the plan by U.S. District Court Judge S. Hugh Dillin, who was overseeing the desegregation case.

IPS’s efforts at self-reform proved to be too little and too late for local political leaders, however. In February 1994, then-Mayor joined with Democrat State Rep. to establish the Alliance for Quality Schools, a political action committee focused on stacking the IPS Board with reform-minded commissioners. After the new PAC failed to gain control of the IPS Board in the 1994 election, Goldsmith took his case for reform to the legislature.

During the 1995 legislative session, Sen. Teresa Lubbers (R-Indianapolis) filed controversial legislation sought by Goldsmith that would break up IPS into five semi-independent districts and impose tough accountability standards on teachers, administrators, and schools. Lubbers’ legislation faltered even after the breakup language was removed, but then key provisions of Goldsmith’s IPS reform package were added to the biennial budget bill and revived in the final hours of the session.

As passed in 1995, the IPS reform law required the IPS Board to set academic performance standards for schools and teachers and to place failing schools in “academic receivership.” Teachers in high-performing schools could receive merit pay, while teachers in low-performing schools could be replaced, subject to existing teacher tenure laws.

The most controversial provision in the IPS reform law limited the collective bargaining rights of IPS teachers to salary, wages, and benefits. Following the 1995 legislative session, the Indiana State Teachers Association repeatedly sought legislation to restore full collective bargaining rights to IPS teachers, but did not achieve a measure of success until 2001.

In addition to authoring the IPS reform bill in 1995, Sen. Lubbers had also been working for several years to gain passage of legislation that would authorize the establishment of charter schools in Indiana. These proposals invariably passed the Republican-controlled Senate but then died in the House. In 2001, however, the ISTA persuaded Rep. Greg Porter (D-Indianapolis) and House Democrats to amend Lubbers’ charter school bill with provisions that expanded collective bargaining for teachers within IPS and repealed the IPS Board’s authority to grant monetary performance awards. The remainder of charter school provisions were largely left intact. The bill was passed by the Democrat-controlled House, and returned to the Senate, where Sen. Lubbers quickly concurred with the changes.

21st-century changes

Under the 2001 charter school law, local school boards, state-funded universities, and the mayor of Indianapolis were all empowered to authorize the establishment of new . School boards were also empowered to convert existing schools to charter schools. Non-public universities were subsequently added to the list of authorizers. Charter schools were not subject to collective bargaining and many other state laws and regulations that school reformers believed hindered innovation and imposed additional costs. Both Mayor and IPS Superintendent Duncan “Pat” Pritchett moved swiftly to develop an application process for potential charter school organizers.

While the city’s charter school program quickly flourished, by 2003 IPS had abandoned its efforts to establish its own charter schools after it failed to attract high-quality applicants. Ball State University also developed a robust charter school program and began opening charter schools in Indianapolis. By 2011, there were 24 charter schools in Indianapolis serving more than 10,000 students. The vast majority of these charter schools were located within the IPS boundaries.

The explosion of charter schools within IPS resulted in enrollment shifts as students left IPS to attend the new charters. From 2001 to 2011, IPS enrollment dropped by nearly 8,000 students. Then in August 2011, the Indiana State Board of Education voted to take over four persistently low performing IPS schools—Emma Donnan Middle School, Arlington High School, Emmerich Manual High School, and T. C. Howe High School—and enter into contracts with private turnaround operators in an effort to boost the schools’ performance.

In 2013, the IPS Board hired a reformed-minded superintendent from North Carolina who had a track record of turning around low-performing schools. Unlike his predecessors who had unsuccessfully fought the expansion of charter schools in IPS, Dr. Lewis Ferebee partnered with then-Mayor to successfully lobby for legislation during the 2014 General Assembly that authorized IPS to establish a network of schools that would operate independently from IPS but still be considered part of the Indianapolis Public School system.

Under the so-called “Innovation Network” legislation, IPS was authorized to contract with charter schools and other outside entities to operate existing IPS schools and to partner with charter schools to open new IPS schools. The legislation was expanded statewide in 2015, but as of the 2020-21 school year, IPS is the only school district in Indiana with an innovation network.

Indianapolis Public Schools today

The Indianapolis Public School system looked much different at the city’s bicentennial in 2020-21 than it had only a decade earlier. Under the leadership of Aleesia Johnson, the first Black woman appointed as superintendent of IPS, enrollment in IPS stabilized after years of small but steady decline. The four schools that had been taken over by the State Board of Education were returned to IPS. The innovation network grew to include 27 schools, more than half of which were charter schools operating in IPS buildings. In the 2020-21 school year, almost 1/3 of the district’s approximately 30,000 students were enrolled in an IPS innovation network school.

But new challenges also loom on the horizon for the state’s largest school district. As of the 2020-21 school year, nearly 3,800 students who lived in IPS are attending private schools under the state-funded voucher program. This number is expected to balloon in the years ahead under legislation adopted by the 2021 General Assembly that increased the amount of the vouchers and substantially expanded the eligibility requirements.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also taken a toll on the district, as parents kept their children out of preschool and kindergarten and students in the other grades fell behind when IPS was forced to switch to virtual classes. Although both the state and federal government provided funding to help school districts address the COVID-19 learning loss, it will likely take years for students in IPS and other school districts to catch up to their pre-pandemic peers.

In the 2020-21 school year, more than 46,000 children who lived within IPS boundaries were receiving a state-funded K-12 education. Approximately 2/3 of those students were enrolled in a traditional IPS school or an IPS innovation network school. Of the remaining students, 8,050 were enrolled in charter schools that were not part of the IPS innovation network, 3,807 had transferred to another school district, and 3,781 were attending a non-public school under the state’s school choice voucher program.

As of 2021, IPS is a majority-minority school district. Nearly 44 percent of students are Black, and another 30 percent are Hispanic. More than two-thirds of IPS students are economically disadvantaged, and 20 percent have recently immigrated to the United States and are still learning to speak English.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.