Crispus Attucks High School was the city’s response to pressure to segregate public secondary education. In the 1920s, most of the city’s elementary schools were already segregated, but the lack of a separate secondary school forced the public school system to enroll Blacks in existing high schools. Late in 1922, the school board recommended the construction of a separate high school for Black students. Segregationist sentiment was so widespread that even Black students entering their senior years at Manual High School, , and had to transfer to segregated Crispus Attucks High School when it opened. Advocates of the new school claimed that It would encourage “self-reliance, initiative, and good citizenship” with a “maximum educational opportunity.” The school board also proposed to employ Black teachers, who were denied the opportunity to teach at the other high schools in the city.

The conservative social, economic, and political atmosphere that resulted in the city’s segregated schools was exemplified by the 1924 election of members to state and local offices. In Indianapolis, the Klan controlled the office of mayor and the city council, resulting in segregationist policies that alarmed the Black community and set the stage for sharp racial divisions. Support for separate schools also came from multiple groups in the city, many of which had been publicly agitating for a segregated high school since the early 1900s. For example, the Federation of Community Civic Clubs, Chamber of Commerce, White Supremacy League, and the Mapleton Civic Association had each lobbied the school board to this end. In 1925, a slate of school board candidates—the so-called “united Protestant Ticket”—gained the support of both segregationist community organizations and the Klan, and they appropriated funds for the construction of the new high school.

In the wake of the board’s decision, the (NAACP) filed a lawsuit in the name of Archie Greathouse, a Black resident of the city, charging that students would not receive an equal education in a separate school. The NAACP lost the suit and an appeal, and construction proceeded. Although the school board had originally designated it the “Thomas Jefferson High School,” the Black community successfully lobbied to name it after an African American historical figure. The name Crispus Attucks honors a runaway enslaved person who was one of the first to die for the cause of the American Revolution.

Matthias Nolcox, the first principal of Attucks, assembled a teaching staff of Black professionals from around the country before the 1927 opening. Many of the faculty had advanced degrees in their subject areas and came from teaching positions at Black colleges in the South. The rapid growth of the city’s African American population and a larger than expected number of pupils—1,350 rather than the anticipated 1,000— required an increase in the staff the next year.

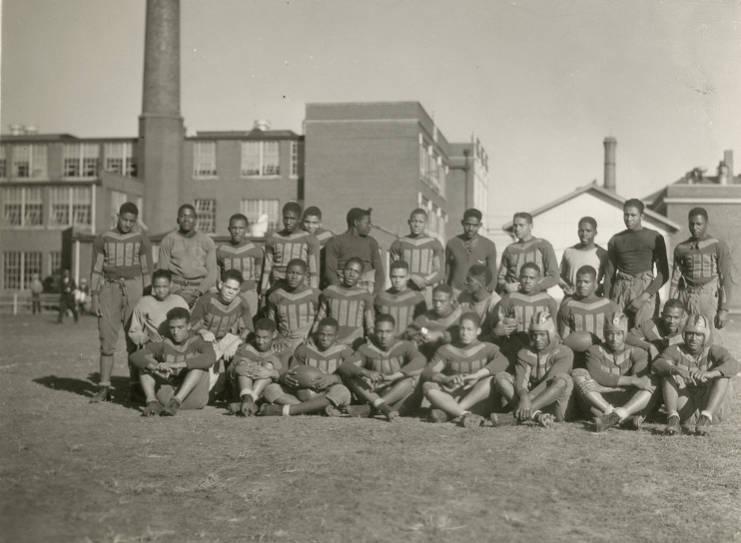

In 1930, Russell A. Lane moved from the English Department to the principalship. During his lengthy tenure (1930-1957), Crispus Attucks gained fame for both its athletic and academic programs. Although it could not participate in sporting events with other city schools, Attucks developed a vigorous athletic program. For many years the banned African American schools from membership—it did not consider Attucks a “public school”—and forbade competition between Black and white teams. Attucks competed with other all-Black schools, many from out of state, or with parochial schools. Finally, in December 1941, the IHSAA accepted Black schools as members.

In 1955, under the leadership of coach , Attucks captured both the all-city and the state basketball championships. Attucks was the first Indianapolis men’s high school basketball team to win in the state contest that began in 1911. Following the championship game, the school’s players, coaches, and cheerleaders got on two fire trucks outside Butler Fieldhouse (now known as ) and were driven south on Meridian Street to . Police sirens and fans cheered a three-mile-long, Attucks motorcade along Meridian Street that included six buses of fans in addition to the firetrucks that carried the team. Mayor , who greeted the team at the Circle, said, “Crispus Attucks is very happy with Indianapolis tonight and happy with the spirit of cooperation everyone is showing us.” Following the ceremony at the Circle, Clark, carrying the championship trophy, led a procession toward Northwestern Park, where 25,000 fans gathered to continue the celebration.

Led by future NBA star Oscar Robertson, the team won the state title against another Black high school, Gary Roosevelt, in the first-ever IHSAA-sponsored Indiana state championship between two African American schools. Crowe’s team repeated its victory in 1956. The team and fans again were escorted to Monument Circle, where Robertson bounded up to the top of the monument’s south steps to great crowd. Coach Bill Garrett fielded another state championship team in 1959.

At no time as a segregated high school did Crispus Attucks have space and facilities to accommodate its student body and faculty. Additions to the structure occurred in 1938 and 1966, but the rapid growth of the city’s African American population outran the space available at the lone Indianapolis public high school for Black students. At one point, when overcrowding became severe, the school board placed School 17, an elementary school adjacent to the high school, under the jurisdiction of Attucks’ principal in the event there was a need for overflow space.

The Attucks curriculum was standard for IPS schools with one exception: Dr. Joseph C. Carroll introduced a course in Black history. Other needs of the school were met in various ways. Spearheaded by prominent Black attorney and a committee from the neighborhood’s , the school raised funds to purchase a pipe organ for its music and drama programs. Over the years the school music program produced many well-known jazz musicians, including , Slide Hampton, , , and Jimmy Spaulding.

As a result of a 1969 agreement between the U.S. Justice Department and IPS to integrate the school system, several Black teachers were reassigned from Crispus Attucks to other city high schools. Included in the plan was the gradual desegregation of elementary student populations. Also included was Attucks’ proposed relocation to a new site that would more readily facilitate school integration. That move, never favored by the Black community, was later dropped.

During the mid-1970s the countywide busing program, which was ordered by the U.S. District Court increased the number of secondary schools in which Black students were enrolled, including township schools in the suburbs. The result was a marked reduction in the number of Black high-school-age students attending Indianapolis public schools. In addition, the construction of the lUPUI campus and the I-65/I-70 inner loop eliminated much of the neighborhood that formerly housed Attucks students. In the late 1970s, after assigning city high schools to four attendance areas as part of the desegregation plan, Crispus Attucks became a magnet school specializing in the medical professions and health-related fields. In a final step, as the redirection of feeder schools to outlying areas reduced the enrollment of city high schools, Attucks became a junior high school in 1986, and, in 1993, a middle school. In 2006, it became a magnet high school again for students interested in careers in medicine.

In 1997-1998, the opened under the direction of the African American History-Multicultural Education Office. The museum houses memorabilia from the former Attucks High School and 14 Black elementary schools. Crispus Attucks was included on the National Register of Historic places in 1989.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.