Although not a principal originator of jazz music like New Orleans, New York, and Chicago, Indianapolis possesses a rich jazz heritage, centered especially in the city’s African American community. By the turn of the 20th century, the capital city was a favorite place for touring musical shows of all kinds, and there was much work for local musicians. The city also was a major ragtime center and was home to such important composers and performers as , Will B. Morrison, Abe Olman, Paul Pratt, , and the young black composer Russell Smith.

In the 1910s and 1920s, Indianapolis venues such as the Washington Theatre attracted a steady stream of top Black performers who played the circuit including gifted brass bands, pianists, singers, and instrumentalists. Among them were The Pickaninny Band (later renamed Deacon Hampton’s Family Band), Frank Clay’s Military Band, and The Kioda Barber Band. Local bands included the Reginald DuValle Orchestra, the Russell Smith Orchestra, and the Harry Farley Orchestra which included a young .

During the late 1920s and the 1930s, Indianapolis musical venues continued to host performers such as cornetist Frank Clay at the Washington Theatre, Nina Reeves and pianist Jesse Crump at the Golden West, blues specialists and at the Paradise, and Zack Whyte’s Chocolate Beau Brummels, Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, Alphonse Trent, Bennie Moten, and Andy Kirk at Denver and Sea Ferguson’s Cotton Club on Indiana Avenue.

Several important local bands came to prominence in the 1930s. The Brown Buddies originated at and included Beryl Steiner, Roger Jones, Renuald Jones, and James (Step”) Wharton. The , comprised of talented musicians from one of Indianapolis’ most important musical families, came up during this time. Led by Clark Hampton, Sr., the band included sons Clark Jr. (Duke), Marcus (Buge), Maceo, Russell (Lucky), and Locksley (Slide) and daughters . Other bands included Fred Wisdom’s Merrymakers, The Patent Leather Kids featuring trumpeter Raymond (Syd) Valentine, and saxophonists Buddy Bryant and Cleve Bottoms.

Those early years were exciting, fruitful, and undeniably important years for jazz in Indianapolis. However, even though Indianapolis musicians were active on both the local and national levels, they did not have the impact of those from the 1940s, 1950s, and early 1960s. These decades constituted a golden age for jazz in the city, producing jazz artists who achieved national and international recognition and created an unprecedented stream of innovative, high-level jazz.

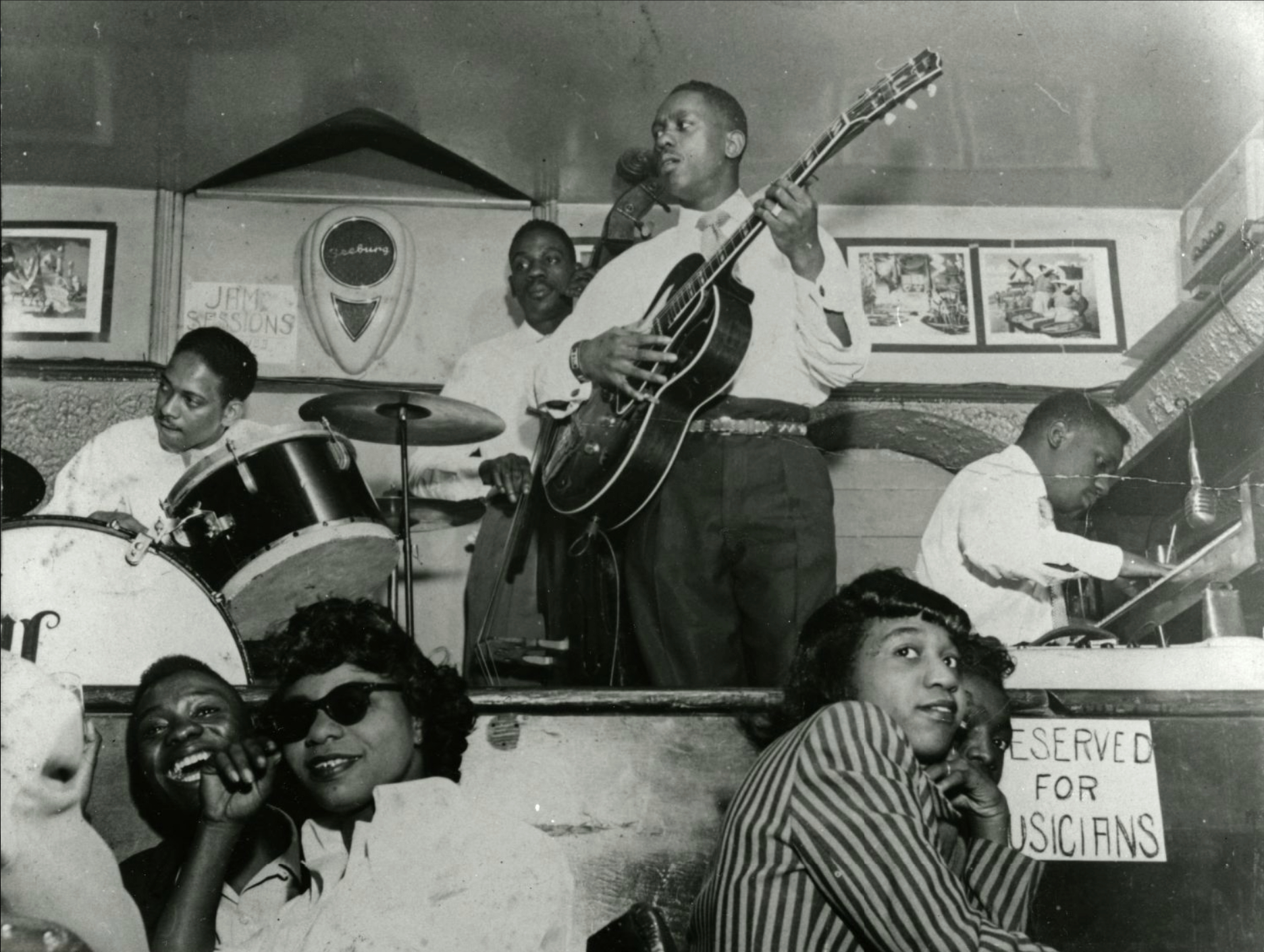

The venues for jazz during this period were many and varied widely in the audiences they attracted. Jazz groups appeared in clubs that primarily served Blacks, clubs that served whites, Black and tan clubs, theaters, lounges, art galleries, dance halls, and after-hours clubs. A major center of jazz activity was , sometimes referred to simply as “The Avenue.” It stretched several blocks from —a New Deal housing project, to Ohio Street–the beginning of Indianapolis’ downtown area. The Avenue boasted many jazz venues including the Cotton Club, the Sunset Terrace, George’s Bar, Henri’s, the Red Keg, the Red Rooster, the Ritz Lounge, the Sky Club (after hours), the Trianon Ballroom, and the Walker Casino. Off Indiana Avenue on West Street (now Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive) was the Missile Room and on Capitol Avenue the Pink Poodle.

Downtown featured the Circle and Indiana theatres, both of which featured jazz bands on a semiregular basis, as well as the 500 Bar, the Beachcomber, the 1444 Art Gallery, and . Sixteenth Street, a main cross street, boasted the 16th Street Gallery, the 16th Street Tavern, and the Turf Bar. Located at 11th Street and Capitol Avenue was the Ferguson Hotel, owned by the , Denver and Sea, who also owned the Cotton Club and the Sunset Terrace. On the near northside were such clubs as the Cactus Club, Mr. B’s, the Hub-Bub, the 19th Hole on 30th Street, the Topper on 34th Street, Stein’s on North Meridian, and the Tropic Club on East 10th Street. In these clubs, theaters, and bars, and at countless private jam sessions, Indianapolis’ jazz musicians, some destined for worldwide fame and others who would remain unknown outside of local circles, practiced and sharpened their often-considerable skills.

The years between 1945 and 1965 represent the period during which the impact of jazz musicians from Indianapolis was the most obvious and quantifiable. The following includes some of the Indianapolis musicians who achieved national or international recognition, as well as other noteworthy musicians who played regularly in Indianapolis. Numerous other figures of comparable skill, imagination, and abilities chose to remain and perform in Indianapolis and developed a local following.

Guitarists:

is considered one of the most influential jazz guitarists, after Charlie Christian. Floyd Smith, who was born in St. Louis but spent much of his creative life in Indianapolis, played the first electric guitar solo on record, “Floyd’s Guitar Blues,” with Andy Kirk in 1939. Another notable guitarist is Ted Dunbar, originally from Port Arthur, Texas, who was a creative force in Indianapolis for many years and remained a leading jazz educator until his death in 1998.

Bass Players:

, brother of Wes, pioneered the electric (Fender) bass ca. 1951-1953, while in the Lionel Hampton band and was the first to specialize and record on it (1953). Indianapolis-born Leroy Vinnegar, a specialist in “walking” bass, was one of the major voices in jazz on the West Coast and is among the most recorded of jazz bassists, along with such artists as Andre Previn, Shorty Rogers, and Harold Land. Laurence (Larry) Ridley, another Indianapolis native, worked with Thelonious Monk, Horace Silver, Art Blakey, Sonny Rollins, and others, and became an important figure in jazz education at major universities.

Pianists:

Charles (Buddy) Montgomery, younger brother of Wes and Monk, was the vibist with The Mastersounds and pianist with Miles Davis and Kenny Burrell. He became a recording artist of great stature in his own right. Indianapolis-born Carl Perkins performed or recorded with Jay McNeely, Miles Davis, Illinois Jacquet, Chet Baker, Clifford Brown, and Max Roach. , a native of Virginia and long-time resident of Indianapolis, was the legendary “godfather” of jazz players of the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. Lanny Hartley played and recorded with The Fifth Dimension. Melvin Rhyne was a pianist and organist with the Wes Montgomery Trio, Slide Hampton, and others. Tipton native John Bunch played piano with Tony Bennett, Benny Goodman, Woody Herman, Buddy Rich, Gene Krupa, and Maynard Ferguson.

Drummers:

Earl (Fox) Walker was the mainstay of one of Lionel Hampton’s most famous bands (with Charles Mingus). Sonny Johnson was a member of the Montgomery-Johnson Quintet and in Lionel Hampton’s band with Clifford Brown, Quincy Jones, Art Farmer, Jimmy Cleveland, and others. “Killer Ray” Appleton worked and recorded with , Slide Hampton, Jimmy Spaulding, and others. Paul Parker played with Wes Montgomery and David Young, among others.

Trombonists:

, the single most important trombonist in contemporary music, jazz or otherwise, revolutionized the approach to the instrument. Locksley (Slide) Hampton played with Lionel Hampton, Maynard Ferguson, Dizzy Gillespie, Art Blakey, Lloyd Price, and many others, and led Slide Hampton & The Jazz Masters. He was also a major jazz composer and arranger. played with Lionel Hampton, Quincy Jones, Stan Kenton, and George Russell, and became Distinguished Professor of Music and chair of the Jazz Department at Indiana University. Phil Ranelin worked with Freddie Hubbard and others.

Trumpeters:

Roger Jones played with Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Tiny Bradshaw, Earl Bostic, Don Redman, and Cab Calloway. Freddie Hubbard was a contemporary giant of the trumpet. Virgil Jones played with Lionel Hampton, Billy Taylor, and others. He appears on countless small group recordings. Alan Kiger recorded with George Russell and John Lewis. Lee Katzman recorded with Stan Kenton and also The Baja Marimba Band. Joe Mitchell played with Earl Bostic when John Coltrane was in the group.

Saxophonists:

Indianapolis native Jimmy Spaulding performed and recorded with Freddie Hubbard, Sun Ra, Duke Ellington, Max Roach, Art Blakey, Horace Silver, and others. worked with Jay McShann, Buddy Bryant, and Tiny Bradshaw. He is also a jazz educator. Charles Tyler, a major figure in the jazz avant-garde, performed and recorded with Albert Ayler, Dewey Redman, David Murray, Cecil Taylor, and Billy Bang. David Young performed and recorded with Lionel Hampton, Mercer Ellington, George Russell, and others. Les (Bear”) Taylor, who worked with Slide Hampton and Bill Doggett, also was a jazz educator.

Groups:

Several jazz groups with roots in Indianapolis include (1930s-1940s), the Mastersounds (1957-1960), the Wes Montgomery Trio (1950s), the J. J. Johnson Quintet (1940s), the Four Freshmen (a quartet from Columbus, Indiana, and Butler University, 1940s-1950s), and the David Baker Quintet (which became The George Russell Sextet).

The mid-1960s and early 1970s saw the beginning of a decline of jazz as a force in the musical life of Indianapolis. Several factors contributed to this phenomenon. Among the more important was the dispersal of the Black population, the death of the jam session as a learning place and proving ground, the loss through attrition of many of the mentors and master players, and the demise of Indiana Avenue as a focal point of jazz and Black culture, including the closing of most of the traditional jazz venues.

By the 1990s, jazz in Indianapolis began a slow, grassroots revival through new venues, education, and events. A few clubs began featuring jazz like the on Massachusetts Avenue and the in , both of which became the pillars of jazz in the city. There were also a number of young musicians making their presence felt on the local scene. In 1994, Hazel Johnson-Strong and Mack Strong even founded the Inner City Music School to provide jazz education to low-income inner-city students. In an effort to preserve and continue the city’s legacy of jazz, the was formed in 1996.

Three years later, the foundation began what became an annual citywide cultural event, the Indy Jazz Fest. The festival brought the city together to celebrate jazz through performances, classes, and various events.

Throughout the early 2000s, interest in jazz increased, proving that the jazz scene in Indianapolis was still very much alive with many of the standard songs from its glory days still being played. Several venues began launching regular jazz events such as Square Cat Vinyl’s all-ages jazz jam. Jazz Appreciation Month also aimed to spur talk about the city’s jazz scene and bring a focus to musician development.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.