In the early 20th century Indiana Avenue became the focal point of the African American community, with segregated business places, leisure venues, churches, and homes on and along the Avenue. Indiana Avenue appears on original plat of the city (1821) as one of four diagonal thoroughfares. It extended northwest from the intersection of Illinois and Ohio streets to end at the corner of the .

A modest number of white Hoosiers, European immigrants, and African Americans alike started enterprises along Indiana Avenue before the Civil War, and most were grocers and craftspeople serving farmers who entered the city on Indiana Avenue. David Burkhart, for instance, came to Indianapolis in about 1824 and founded perhaps the first grocery on the Avenue, where he sold household provisions as well as alcohol. The 1858 city directory identified eight groceries, two physicians’ offices, a boot shop, an ice dealer, and a carpenter’s shop on Indiana Avenue, revealing the street was gradually becoming a retail district.

Among the first grocery stores on Indiana Avenue were several of the city’s first African American businesses. In 1850, Thomas Bushrod appeared in the census as a grocer, probably operating the store with his wife Nancy on Indiana Avenue. After Thomas’ death, Nancy Bushrod married Samuel G. Smothers, and Samuel and Nancy purchased a lot at 515-519 Indiana Avenue and opened a grocery. Nancy opened a restaurant there after the Civil War that became popularly known as the “Beanery,” and in the early 20th century her daughter Anna Smothers Bowman assumed management of the restaurant.

Indianapolis expanded quite rapidly in the wake of the , but the 1870 city directory still identified only 10 of the 109 households on Indiana Avenue as “Colored.” A decade later 682 individuals had residential addresses on Indiana Avenue, and 115 were identified as Black or “mulatto.” Over two-thirds of the Avenue’s residents in 1900 were identified as white (69 percent), but the percentage of Black/”mulatto” residents grew from just less than 17 percent in 1880 to almost one-third in 1900. Most of the African American residents were born in Kentucky, reflecting a consistent African American migration from Kentucky that began in the late-19th century and would continue through the 20th century.

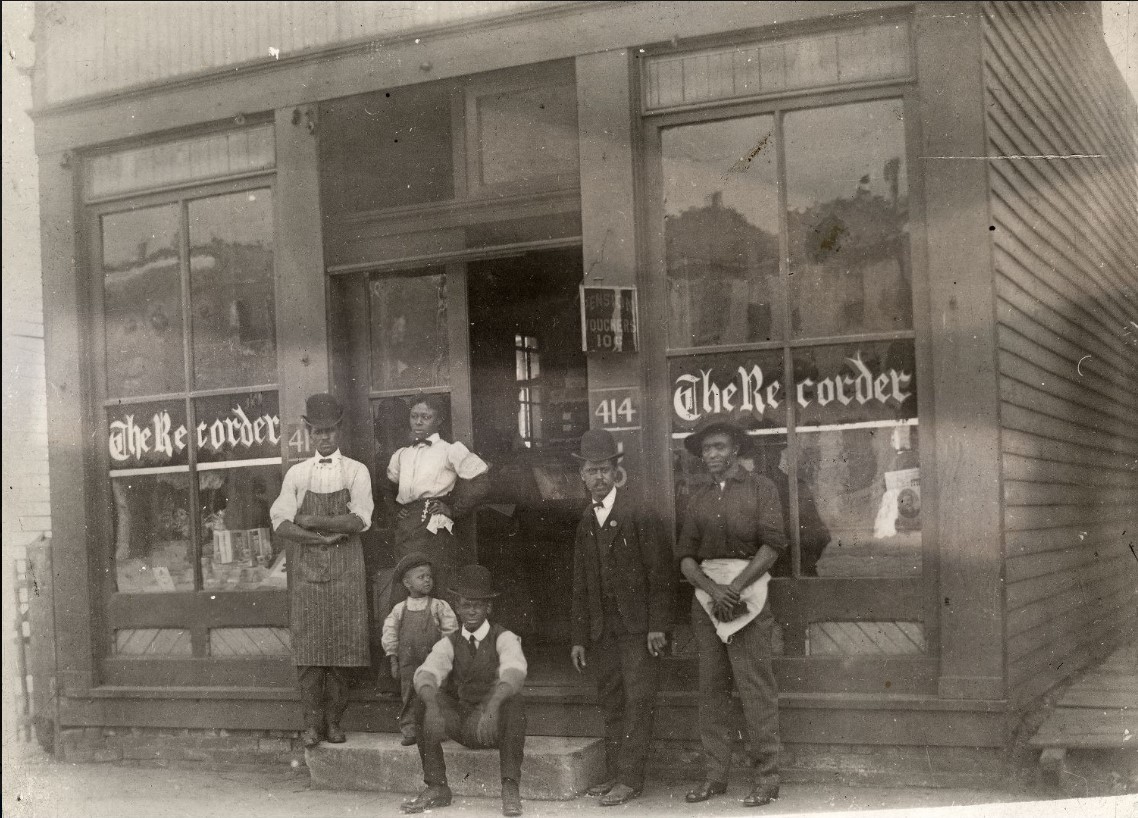

During the early 20th century, waves of African American migrants moved into the near-west side, and many white residents moved out as Indianapolis rapidly became segregated. The Avenue was a predominately African American marketing and leisure district by 1920 when 77 percent of the Avenue’s residents were identified as Black. In 1916, the businesses along Indiana Avenue included 33 restaurants, 33 saloons, 26 grocery stores, 17 barbershops, and hair stylists, 16 tailors and clothing stores, 14 shoemakers, 13 dry goods stores, several undertakers, a bicycle repair shop, and Plaza Hotel. Many Indiana Avenue residents were employed as domestics or as manual laborers in local foundries, factories, or processing plants. Nevertheless, some of the very first African American professionals established enterprises along the Avenue by the turn of the century. The city’s first African-American physician, established an office on the Avenue in 1895. In 1900, began to practice in the 400 block, and he was admitting patients to his private Ward’s Sanitarium hospital in the 700 block of Indiana Avenue by August 1906.

In May 1910, there were three theaters on Indiana Avenue: the Airdome Theater, at 523 Indiana Avenue (which became the Crown Garden in 1910); the Columbia Theater, at 524 Indiana Avenue; and the Two Johns Theater, at 720 Indiana Avenue. The Two Johns Theater (named after its white owners John B. Hubert and John A. Victor) would become best-known for the serial films it featured until it closed as the Lido in 1959, but its early shows featured performers.

The Avenue’s earliest grocers often sold alcohol alongside a host of provisions. The city directory did not include a saloon on Indiana Avenue until 1865. These would rapidly become prominent performance and social spaces following the Civil War. The 16 saloons on the Avenue in 1890 mushroomed to 33 in 1914. One of the earliest African American saloons was opened by Archie Greathouse in 1889, and Greathouse managed saloons and restaurants on the Avenue until he died in 1936.

Most of the early criticism of Avenue life came from crusaders. The moral resistance to saloons was in part an attack on gambling. Dice, billiards, numbers games, and pools were a staple of all saloons long into the 20th century. Archie Greathouse, for instance, lorded over Prohibition alcohol sales, orchestrated gambling, and supervised or at least permitted a host of minor vices that would make him a common target of moralists for more than a half-century.

Some of the surveillance of saloons also was an attack on political activism based in many African American saloons. Between about 1882 and 1909, saloon keeper and Civil War veteran Henry Seaton presided over an African American organization that campaigned for candidates, lobbied against voting fraud, and made statements on civil rights violations like lynching. Archie Greathouse was among the most prominent activists opposing the segregation of Indianapolis high schools in the early 1920s, and he funded lawsuits to oppose high school segregation.

In 1917, the Indiana General Assembly approved a statewide Prohibition law that went into effect starting in April 1918, and many saloons became “soda shops” while surreptitiously trafficking in alcohol. Restaurants, pool halls, and a host of businesses served as fronts selling bootlegged liquor. Harry “Goosie” Lee was a Republican activist in January 1920, when he was arrested for having 17 one-gallon jugs of whiskey in his car. Lee’s Avenue venues were constantly raided throughout the 1920s, but Lee maneuvered out of any significant prison sentences.

In June 1920, the police announced the creation of a new “morals squad” that ambitiously aimed at “gamblers, would-be gamblers, bootleggers, and women of the underworld.” The squad visited the most prominent Avenue outlets with a history of vice arrests, including Goosie Lee, Archie Young (500 block), Sol Caldwell (300 block), West Alexander (300 block), and William Butler (500 block). Archie “Joker” Young was managing the Golden West Cabaret in December 1921, and when police raided the jazz club they found white men and women dancing and consuming the “white mule” they had purchased at the club.

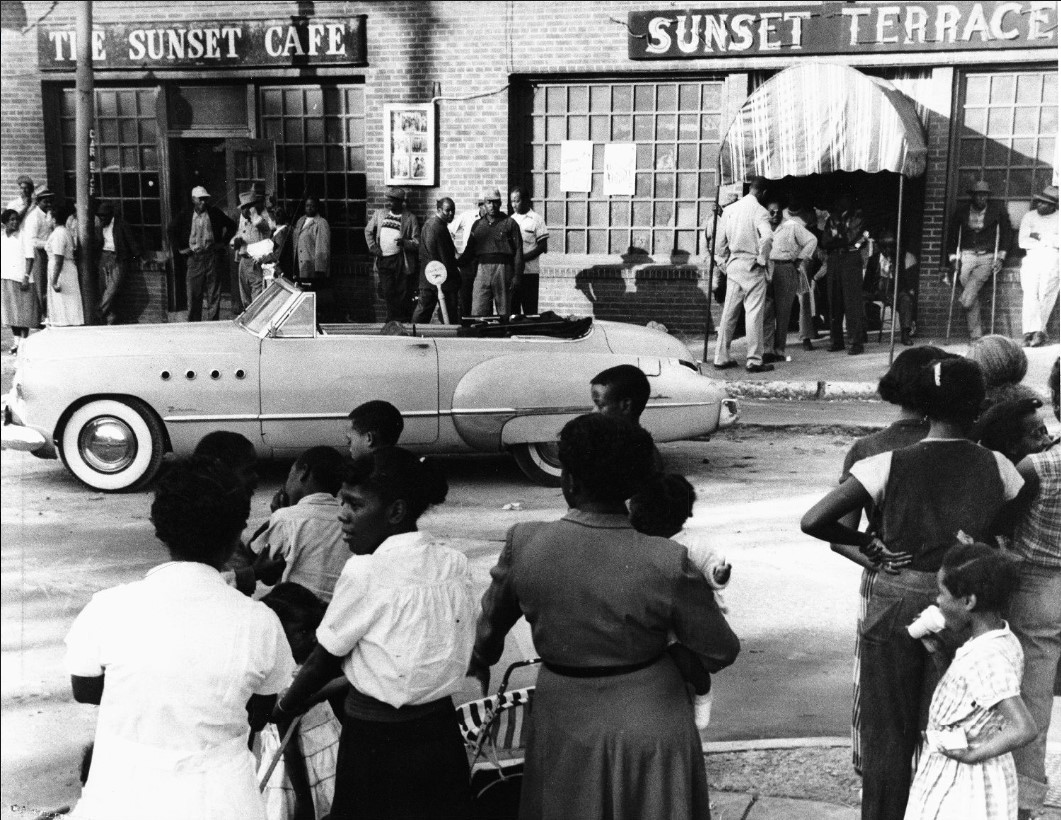

Indiana Avenue was fabled as a center of commercial leisure in the 20th century, and Avenue clubs featured an astounding breadth of African American expressive culture including theater, song, dance, comedy, and drag. African American performance spaces emerged along Indiana Avenue alongside the early waves of Southern migration and increasing segregation. At the end of 1927, Denver Ferguson opened the Rainbow Palm Garden restaurant in the former Liberty Hall building at 427 Indiana Avenue, and a series of clubs occupied the space until the Frederick Douglass Social Club finally closed after it was the target of a 1968 police raid. Denver’s brother Sea opened the Trianon Ballroom in December 1931, part of a rapid growth of clubs along the post-Prohibition Avenue. Sea’s Cotton Club opened on the floor below the Trianon in October 1933. Denver opened perhaps the Avenue’s most famous club, the Sunset Terrace, in December 1937. Covered on its façade with logs and a neon sign, the Log Cabin opened its doors at 524 Indiana Avenue in 1939. William and Margie Benbow opened the Stormy Weather Café in about 1943 at 319 Indiana Avenue. In September 1939, Ruben “Ruby” Shelton and Palmer Richardson opened the P&P (Popularity and Pleasure) at 438 Indiana Avenue. In June 1944, Shelton and Richardson opened the 440 Club, and one of the first musicians to play the club was in what was certainly one of his first Avenue performances. These clubs hosted the nation’s most prominent performers: Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Josephine Baker, Erskine Hawkins, Lionel Hampton, , and scores of others played these clubs. Hometown legends included , , Wes Montgomery, , Leroy Vinnegar, Jimmy Anderson, , Earl Walker, and the .

In the 1920s, an enormous number of palatial movie houses and theaters opened throughout the country. The Avenue’s most prominent theatrical space was the , which opened in December 1927. The theater was named for , the entrepreneur who founded the Indianapolis-based hair care company and died in 1919. The Indianapolis architects designed the triangular “flatiron” building, which was the home to the Walker Company, African American professionals’ offices, the Walker Coffee Pot restaurant, and a ballroom.

Brothers built an empire managing a series of clubs and restaurants. Denver learned the printing trade before serving in World War I, and in about 1919 he migrated to Indianapolis, where he started operating a printing company that brother Sea joined in about 1926. In a city with no African American bank and firm segregation of public services, the Fergusons and men like Archie Greathouse, Goosie Lee, and Archie Young were an essential source of philanthropic support, and they supported loans for residential and marketing real estate in a moment when African Americans had few economic options.

The Ferguson print shop’s products included a host of gambling paperwork, and the shop was constantly raided by police. The Fergusons’ profits allowed them to establish an entertainment empire along the Avenue, but police and federal law-keepers aggressively pursued the Ferguson brothers’ business into the 1950s. The liquor licenses of Denver’s Sunset Terrace, Sea’s Cotton Club, and Goosie Lee’s Oriental Café were all revoked in January 1941 for violations of the liquor law. In August 1942, Sea’s Cotton Club and Joe Mitchell’s neighboring Mitchellyne were closed for “maintaining a public nuisance,” and in January 1943, Sea Ferguson paid a fine and surrendered management of the Cotton Club.

A series of influential clubs opened in the wake of World War II. In January 1945, the British Lounge opened at 643 Indiana Avenue (in May 1968 Indianapolis musician Al Coleman assumed control of the club). In May 1946, the Famous Door Club opened at 318 ½ Indiana Avenue offering restaurant service alongside exotic dancers, drag performances, and musicians including Indianapolis’ Jimmy Coe. In November 1947, Henry Vance opened Henri’s at 408 Indiana Avenue, the former location of Joe Mitchell’s Mitchelynne. A famous plaque over the door proclaimed, “Through These Portals Pass the World’s Best Musicians” (this plaque’s wording is remembered in various ways by different people). In about 1949, George Reid remodeled a restaurant at 413-415 Indiana Avenue that became George’s Bar, and he added the “Orchid Room” in 1951.

In 1952, , the white-owned, prominent commercial radio station, broadcast from George’s one night a week, one of a series of Avenue clubs hosting radio shows. Whites sometimes frequented Indiana Avenue venues, but police and moral ideologues persistently fought against inter-racial leisure and fortified segregation long after the end of Prohibition. In March 1956, for example, the police served notice to clubs along Indiana Avenue that they could not entertain white customers, a somewhat shocking notice that conflicted with state civil rights laws.

In 1958, Indianapolis’ most ambitious postwar urban development plan proposed the creation of a joint undergraduate campus of the state’s two largest universities, Indiana and Purdue, neighboring the campus. Indiana University (IU) had long aspired to expand the IU Medical Center, and in 1954 and 1956, it acquired two tracts neighboring the that had been defined as blighted.

IU gradually pieced together the regional campus from single real estate parcels (between July 1964 and August 1966, for example, the University purchased 401 parcels). The University’s first purchase of property on Indiana Avenue may have been in October 1965, when IU purchased Ruth McArthur’s home at 802-810 Indiana Avenue. McArthur founded the MacArthur Conservatory of Music at the address in 1946, and the school was a staple of Avenue musical education until its closing in 1963.

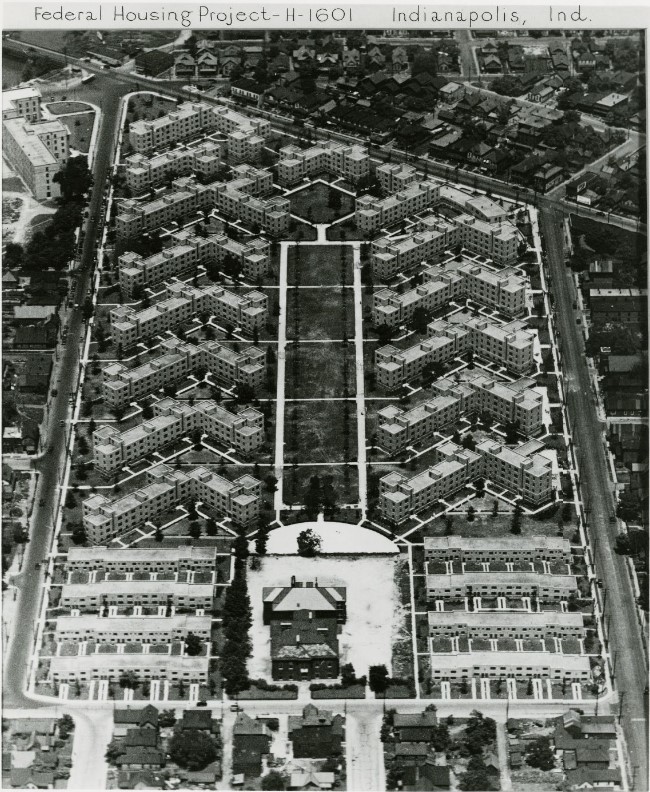

The once-thriving nine-block Avenue was soon reduced to clusters of structures. By 1970, , the city’s first major public housing project which opened along Indiana Avenue in 1938, had declined in the hands of disinterested city administration, and its residents voted in 1971 to approve a renovation plan that would temporarily relocate all residents. The renovation exodus began in May 1973, but in October 1975, Judge ruled that rehabilitating Lockefield for an exclusively or overwhelmingly Black residency illegally reproduced school segregation (See ). By 1977, the city resolved to simply raze Lockefield, leading to a flurry of attempts to preserve the New Deal community. In July 1983, all but seven of the Lockefield buildings were razed.

Perhaps the most famous of the Avenue clubs, the Sunset, appears to have hosted its last shows in April 1966, and it fell to the wrecking ball in January 1987, before the demolition company had secured a permit to raze the building. City-County Council President owned the Sunset property, and he admitted afterward that “now that it’s down I think it’s an improvement.”

The Walker Theater was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980, and in 1987 the 500 block of the Avenue followed, recognizing its significance as a center of African American marketing and leisure during segregation. Nevertheless, a very small handful of historic structures survived urban renewal. For instance, a series of stores occupied the building at 541-543 Indiana Avenue, which was built in 1910, and it became home to the in 2019.

In response to the protests that broke out in Indianapolis and other cities across the nation following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, Indiana Avenue, between West and Paca streets, became home to the in August of that same year. Organizers deliberately chose the site to remind people of both the historical and ongoing displacement of Black communities in this area of the city. It included the works of 18 artists who painted the names and faces of such subjects as Floyd; Dreasjon Reed, fatally shot by an Indianapolis police officer on May 6, 2020; Breonna Taylor, shot by police in Louisville, Kentucky, on March 13, 2020; and shot and killed on September 24, 1987, while in the custody of the . Defaced one week after it was painted, the mural was removed 15 months later to accommodate the two-mile expansion of the from the Madame Walker Legacy Center to the innovation district.

In 2020, Reclaim Indiana Avenue, a community planning initiative that has brought area residents and stakeholders together, stopped a proposed five-story development project on Indiana Avenue that was “out of tune with the neighborhood’s needs and historic character.” The city announced in February 2023 that it would work with Reclaim Indiana Avenue and the Urban Legacy Lands Initiative, another organization formed to find better solutions for the area’s future, to redevelop the district in a way that would highlight and honor the Indiana Avenue area’s history. As part of its Cultural Equity Plan, the city aimed to create “inclusive and racially equitable redevelopment and do so in a way that supports the neighborhood’s historic culture rather than supplanting it.”

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.