Based on white supremacist, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic beliefs, support for enforcement, and a wide range of traditional social, religious, and family values, the Klan became the largest social organization in Indianapolis. It was the dominant force in city politics between 1921 and 1928. At least 27 percent and perhaps as many as 40 percent of all native-born white men in the city paid 10 dollars to become official members of the Klan during this era. A separate women’s organization (Women of the Ku Klux Klan) also existed and may have been quite large, although the actual extent of its popularity is not known.

Political candidates openly supported by the Klan captured Marion County’s congressional seat in 1924, and the mayor’s office, the city council, and the board of school commissioners, among other offices, in 1925. Throughout the state one quarter to one-third of all native-born white men became members, and Klan politicians gained control of the state Republican Party, many of the major local party organizations (both Democrat and Republican), the state legislature, and virtually all of the state’s major elected offices, including that of the governor.

The Klan movement of the 1920s, distinct from the southern terrorist Klans of the Reconstruction era (1865-1877) and the civil rights era (1954-1968), had its beginnings in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1915.

For a number of years, it barely survived as a regional fraternal organization prone to vigilante violence. It was devoted to the idea that sinister forces—primarily Catholics, Jews, and Blacks—threatened American institutions.

In 1920, however, after the onset of national prohibition, Klan leaders began a national marketing campaign that turned the organization in a new, more successful direction. While retaining its bigoted ideological orientation, the Klan promoted itself as an organization of patriotic citizens determined to use politics and other law-abiding means to support prohibition enforcement, traditional moral and family values, patriotism, public education, civic responsibility, and various other concerns.

Millions of Americans rushed to join the Klan or support it with their votes between 1920 and 1925. At least three million and perhaps as many as six million men and women joined from every region of the nation, with the most success coming in areas that were most homogeneously white and tied culturally to a strong evangelical Protestant tradition. The most popular state organizations were in the Midwest. By all accounts, Indiana’s Klan was the largest and most politically powerful in the nation, and its original Grand Dragon (state leader), , was one of the most well-known Klansmen of the era.

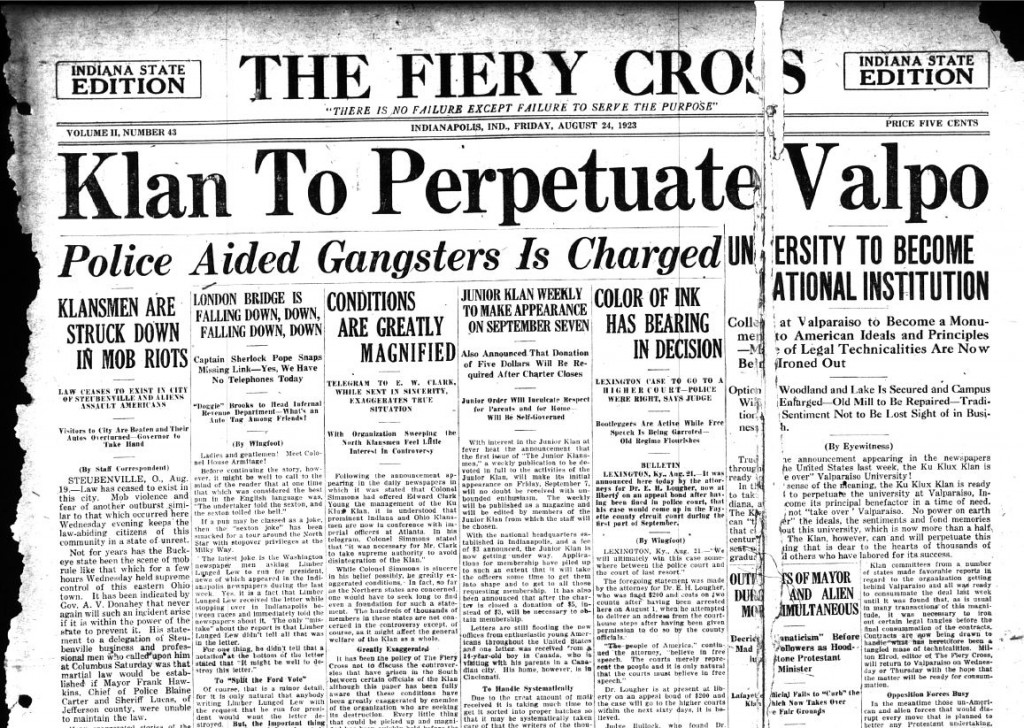

The Klan established its first Indiana chapter in Evansville in late 1920 and quickly organized chapters in every Indiana county. In March 1921, the Klan opened an office in Indianapolis and began soliciting members locally. By summer 1922, the Klan, claiming some 5,000 members, had begun publishing , a weekly newspaper headquartered in the Century Building and supported by local business advertising. Within a year the paper reported a circulation of 125,000 throughout the Midwest.

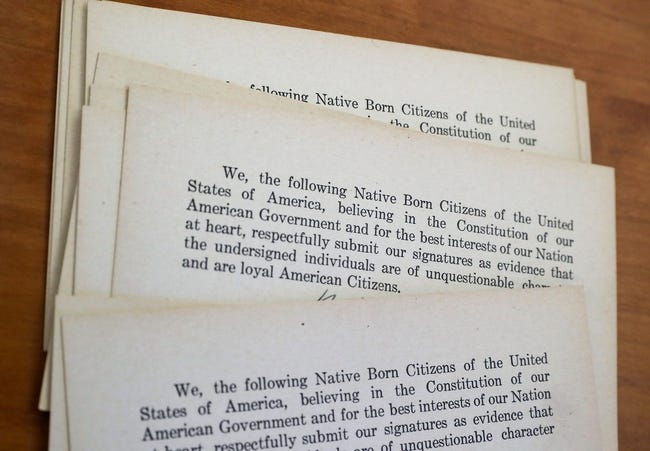

The Indianapolis men who joined the Klan came in large numbers from every area of the city and represented a wide cross-section of the city’s white Protestant society. This was also true throughout the state and in other areas around the nation where the Klan flourished.

Klan members were highly representative of Indianapolis’ occupational spectrum. Successful businessmen, shop owners, and professionals could be found just as frequently in the Klan as they could among the population at large. Less affluent white-collar workers and skilled blue-collar workers joined the Klan at a slightly higher rate than other occupational groups. Semiskilled and unskilled workers were somewhat less likely to join the Klan, but even they were well represented. Only the very rich and the very poor did not belong in significant numbers. For many individuals, the $10 initiation fee (easily a quarter of a week’s pay for well-paid workers) represented an important barrier to Klan membership.

Klansmen also came in representative numbers from virtually all of the city’s major Protestant churches, as well as from that segment of society that did not attend any church. Many of the city’s Protestant ministers were openly sympathetic to the Klan and became active organizers and leaders in the movement.

At the same time many Indianapolis citizens—including many white Protestants—reacted with anger and alarm to the Klan’s great popularity. Naturally, those sentiments ran strongest in the city’s Catholic, Black, and Jewish communities. The , the , and the , all published in Indianapolis, relentlessly attacked the Klan’s bigotry, expressed outrage at its political influence, and encouraged their readers to do everything in their power to stop the Klan. The city’s leading anti-Klan newspaper, the , battled the Klan throughout the 1920s and received a Pulitzer Prize in 1928 for its detailed reports on the Klan’s involvement in bribery and corruption in city, county, and state politics.

One of the bolder anti-Klan actions of the era occurred in April 1923, when Klan opponents—thought to be led by Catholic members of the Indianapolis police force—broke into the city’s Klan headquarters in Buschmann Hall (located at 11th Street and College Avenue), stole a membership list, and later published it in the Chicago-based anti-Klan newspaper, . Publication of the list came as something of an embarrassment to a number of prominent individuals such as Indiana secretary of state Edward Jackson, who would be elected governor a little more than a year later. But the list’s publication, like other anti-Klan activities, did virtually nothing to slow the Klan’s rapidly increasing popularity. Membership almost certainly tripled in Indianapolis within a year and a half after its appearance.

Another opponent of the Klan, the city’s Republican mayor, , also tried to stem the organization’s power, although he, too, failed. Shank prohibited masked parades, refused the use of for a Women of the Ku Klux Klan rally and enforced the Board of Public Safety’s ban on cross burnings. In July 1923, a cross burning in West Indianapolis attracted several thousand people and produced a rock-throwing incident when city firemen attempted to extinguish the fire. The Klan threatened to impeach Shank, accusing him of aiding bootleggers and criminals.

In an effort to break the Klan statewide, Shank entered the Republican gubernatorial primary against the Klan’s candidate, Ed Jackson. In the May 6 primary election, Jackson easily gained the nomination over Shank and other anti-Klan Republicans, defeating the Indianapolis mayor in Marion County by a total of 38,668 to 20,306 votes.

Following his defeat, Shank reluctantly capitulated to the Klan’s political power. He allowed the Klan to hold a massive victory parade, which saw more than 7,000 triumphant Klansmen and Klanswomen march from the on the northside of Indianapolis, through the Black neighborhoods along Indiana Avenue, into the center of the city.

In November 1924, the Klan reached the zenith of its political power in Indiana. Klansman Ed Jackson was elected governor along with a full Klan-endorsed slate of state officials, a Klan-backed majority in the state legislature (including State Senator William T. Quillen of Indianapolis), and all but a handful of the state’s 13 congressional representatives (including Congressman Ralph E. Updike of Indianapolis).

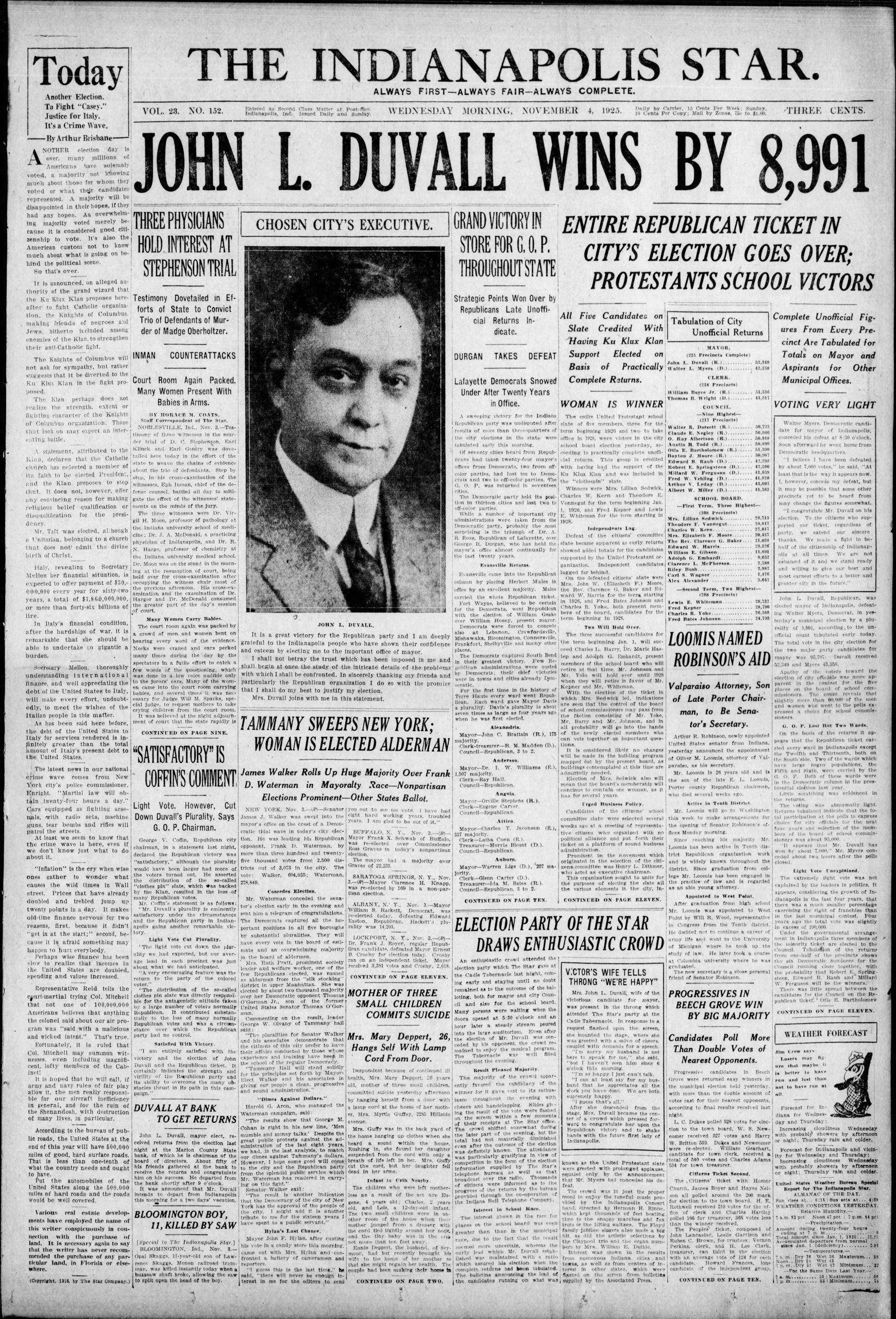

In Marion County, Jackson defeated his anti-Klan Democratic opponent, Carleton B. McCulloch, by a total of 85,740 to 71,876 votes. In the following year, the Klan assumed control of the Indianapolis city government. Shank was replaced by Klansman , who defeated Democrat Walter Myers in the November 1925, municipal election.

A significant number of traditionally Republican voters abandoned the party as the Klan gained control. The largest bloc of disaffected Republicans came from the city’s Black community. Black voters turned overwhelmingly to the Democratic Party during the Klan elections of 1924 and 1925; few would ever return to the Republican ranks.

Local opposition stemmed primarily from the Klan’s reputation as an organization that fomented danger, division, and violence. Klan demonstrations, rallies, and parades—usually culminating in ceremonial cross burnings—certainly underscored this concern. So too did the frequently tumultuous pro-and anti-Klan political demonstrations that accompanied elections. In reality, however, the Klan was a mainstream movement oriented toward politics, not an organization of vigilantes operating on the fringes of society.

Perhaps even more significant, its ideology was far from aberrant in Indianapolis or the rest of American society in the 1920s. The widely held view that white Protestant cultural values should be dominant in society, and that white Protestants could be legitimately viewed as America’s chosen people, lay at the heart of the Klan’s popularity. This mainstream, “populist” message explained the Klan’s successful political insurgency.

In Indianapolis, as throughout the state, the issue of prohibition enforcement was the primary catalyst for white Protestant concerns. While liquor had been outlawed by federal and state law, a vast underground market flourished in Indianapolis just as it did elsewhere. Not only was prohibition enforcement an abysmal failure, but law enforcement officials themselves were corrupt.

When the Klan-backed city council and Mayor Duvall were elected in 1925, “law enforcement” was their central message. But the city’s Klan politicians proved just as ineffective as their predecessors at enforcing the liquor laws—and just as corrupt in other areas. A series of scandals forced Duvall and the entire Klan city council out of office before the completion of their terms.

The Klan’s populist politics spilled over into other areas as well. The Indianapolis Klan became deeply involved in a complex and controversial battle over the expansion of the city’s public school system during the 1920s. In the early part of the decade, the school system was the target of public criticism for its poorly maintained, overcrowded facilities. In 1921 and 1923, Indianapolis voters passed bond issues to support the construction of new elementary and high schools. Throughout these years, however, city business leaders who controlled the Indianapolis Board of School Commissioners through an organization known as the Citizen’s School Committee blocked these construction projects.

Combining its support for the building program with anti-Catholic rhetoric directed at board president Charles W. Barry, the Klan slated five candidates (known as the Protestant School Ticket) in the 1925 election and swept the Citizen’s Committee off the school board. Over the next four years, the school board carried out the building program that the previous board considered “extravagant.” One of the schools built during this era was the racially segregated . The Klan-dominated school board naturally favored this development. But so too did its opponent, the Citizen’s Committee, which originally devised the segregation plan and maintained it while controlling the school board from the late 1920s into the 1950s.

Higher school taxes were controversial in Indianapolis during the 1920s; segregation was not. The Klan-dominated city council subsequently passed a law to segregate the city’s residential neighborhoods, but federal courts threw out the law before it ever went into effect.

The conviction and subsequent imprisonment of former Indiana Grand Dragon D. C. Stephenson on the charge of second-degree murder in 1925 played an important part in discrediting the organization. Nonetheless, many Hoosiers remained silent, including political leaders, newspaper editors, and Protestant ministers.

Not until the local elections of 1929 did Indiana voters reject the Klan’s political allies in the Republican Party. Criminal charges against Klan leaders and politicians, including Governor Jackson, caused gradual disaffection. Growing public disillusionment with prohibition also contributed to the Klan’s decline. Once Klan politicians demonstrated that they were just as unable as other government officials to stop the flow of illegal liquor, many supporters simply gave up on the idea that the prohibition laws were enforceable.

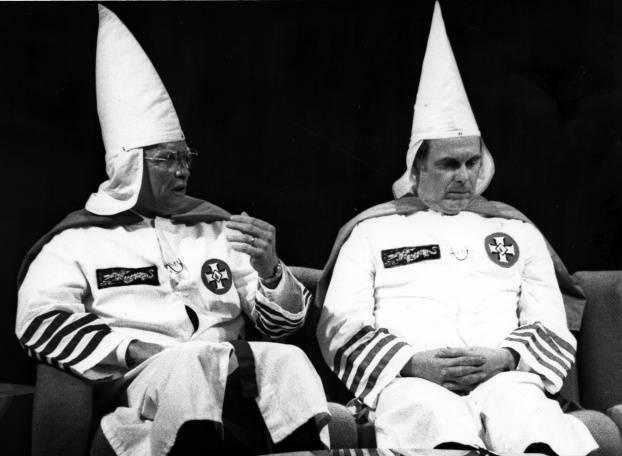

Remnants of the 1920s Klan movement would linger into the 1930s, to be revived in the 1960s as protest against the civil rights movement. Into the 21st century small, sometimes violent, hate groups bearing the Klan’s name continue to exist. None of these groups, however, would match the massive, mainstream popularity of the Indianapolis Klan of the early 1920s.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.