Throughout its history, the Jewish community of Indianapolis has comprised approximately 1 percent of the city’s total population. Jewish immigration to the city, however, occurred in distinct waves over time, each representing people of different national origins who possessed different cultural and religious practices.

The first Jewish residents in the capital city appear to have been Polish-born merchant Alexander Franco and English-born clerk Moses Woolf, who arrived in 1849. Other Jews of predominantly German origin took advantage of the city’s first railroad, which linked Madison with Indianapolis in 1847, and moved here in the 1850s.

Many early Jews were German peddlers turned small merchants or residents of small Indiana towns who shared pride in German culture and achievements through their support of local German associations. Jewish merchants soon dominated the city’s clothing business, operating 10 of 18 clothing stores in 1860. By the 1880s one half of the German Jews were shopkeepers, retailers, and wholesalers; others were involved in peddling, tailoring, and assorted professions.

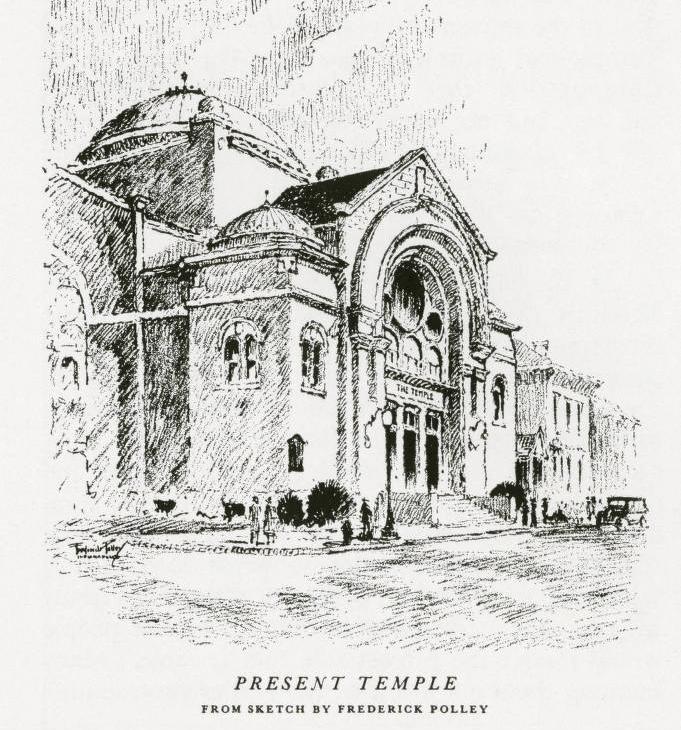

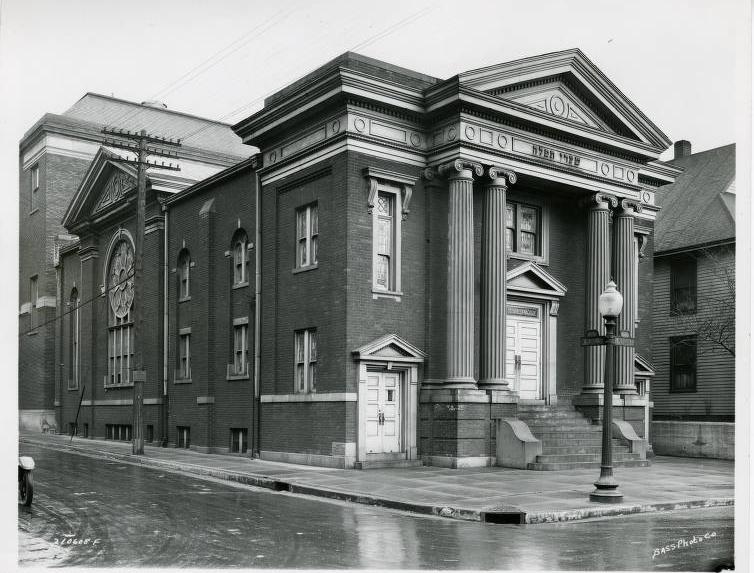

The Jewish population, which grew from 180 in 1860 to more than 500 by the 1870s, was quick to establish ethnic enclaves on the near south and east sides of Indianapolis. Fourteen male Jews from Knightstown, Kokomo, and Indianapolis (most of whom resided in the area bounded by Washington, Alabama, New York, and East streets) organized , the city’s first synagogue, in 1856. The founders erected their first temple in 1865 on East Market Street between New Jersey and East streets, in the old Germantown area where many of them lived.

Synagogues quickly became the focal point of a close-knit community. They started clubs, benevolent associations, a cemetery at South Meridian and Kelly streets, and a school. With an established community, Jews began to take an active part in local politics. Leon Kahn was the first Jew elected to the Indianapolis Common Council, serving eight years between 1869 and 1884.

Civic and business leaders also emerged from this group, including , , and Henry Kahn. The , of December 6, 1894, counted Jewish merchants Herman Bamberger and Leopold Strauss among the city’s leaders. With increased affluence and assimilation, however, German Jews moved from the old Germantown to the emerging residential areas along North Meridian Street south of Fall Creek.

During the late 1880s central and east European (particularly Hungarian, Polish, and Russian) Jews, known as Ashkenazim, began to arrive. Speaking different Yiddish dialects though possessing similar cultural and religious practices, these Jews were divided according to national or regional origins. The Ashkenaziim settled on the south side in an area bounded by Morris Street, Capitol Avenue, Union Street, and Washington Street. They became a visible minority, characterized by cultural practices, Orthodoxy, language, and separate institutions. These east European Jews were commonly employed as artisans, garment workers, carpenters, and cabinetmakers working for automobile and furniture manufacturers, or hucksters and pushcart vendors.

In 1906, a small wave of Sephardic Jews from the Ottoman Empire (Salonika and Monastir, now Bitola, in Macedonia) came to Indianapolis. Their principal language, Ladino, made communication with the eastern Ashkenazim impossible except by using English. Labeled derogatorily as “Turks” and considered “not really Jewish,” the Sephardim lived among the east European Jews along South Illinois and South Meridian streets, but maintained their own unique institutions. Until after World War II, intermarriage between Ashkenazim and Sephardim took place rarely if at all. Northside Jewry and southside Jewry differed in many ways.

The predominantly German Jewish north side practiced Reform Judaism and attended the Indianapolis Hebrew Congregation; the east European Jews on the south side practiced Orthodoxy, a more strict observance of Jewish law and customs, and maintained several ethnic congregations (Shara Tefilla, Polish, 1882; Ohev Zedeck, Hungarian, 1884; and Knesses Israel, Russian, 1889). Reform Jews tended to oppose political Zionism, arguing that was a religion and that Americans of the Jewish faith should pay allegiance to the United States. Most Orthodox Jews, while not agreeing with all aspects of political Zionism, supported the concept of an eventual return to Zion and the possibility of creating a Jewish state.

Both nationally and locally based Jewish organizations helped the eastern Ashkenazim and Sephardim adapt to American life. In 1901 the national B’nai B’rith established the Industrial Removal Office to disperse Jewish immigrants throughout the United States. This resulted in the formation of the local Jewish Welfare Federation (1905, now ), designed to consolidate fund-raising efforts and to dispense relief to the poor. Indianapolis Jewish leaders like rabbis and Mayer Messing, industrialist Samuel Rauh, and merchant Gustave A. Efroymson were among the many prominent Jews who were devoted to local civic life as well as to assisting recent immigrants to assimilate into American society. Other groups like the and the House provided educational and social service programs for recent arrivals.

Although strong nativist sentiments and restrictive immigration laws deterred Jewish immigrants in the post-World War I years, Indianapolis recorded 42 percent of the state’s Jewish population in the 1920s. With the rise of Nazism and Hitler’s persecution of the Jews, however, central European (German and Austrian) Jewish refugees began arriving in Indianapolis in 1938; by 1941 there were about 250 in the city.

Unlike their skilled and unskilled predecessors, these refugees were primarily professionals or businessmen. Local Jews put aside their own cultural differences to assist these refugees in adapting to American life. By this time only the Sephardim lived exclusively on the south side; the majority of the Jewish population lived in the rapidly growing north side above 38th Street. By 1948 over 11 percent of employed Jews were professionals; 19 percent in sales; 43 percent proprietors; and 27 percent manufacturers and other workers.

Following World War II, the Indianapolis Jewish community joined the nationwide United Jewish Appeal to raise funds for the surviving European Jews. Local contributions rose from $196,000 (1945) to $625,000 (1946) and $1,004, 600 (1948). After the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, larger portions of local funds went to support local synagogues, homes for the elderly, hospitals, and Jewish community centers.

In the 1970s, Soviet Jews comprised the fifth wave of Jewish immigration to the city. They were, for the most part, non-practicing Jews who considered themselves Jews by reason of birth. Many of the synagogues and community organizations, including the Jewish Community Center (established 1926), assisted the Soviet emigres by providing language education, housing, and employment assistance. Since the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, several hundred Jews who emigrated from the former Soviet republics to escape increased anti-Semitism have settled in Greater Indianapolis.

Throughout the city’s history, the Jewish population faced minimal discrimination, due in part to their small numbers and early involvement in Indianapolis’ civic, economic, and cultural life. By the 1920s, a period of rampant xenophobia and nativism, Jews were being excluded from private clubs, certain neighborhoods, and jobs. The directed its campaign of hate against Catholics, African Americans, and Jews, and targeted Jewish-owned businesses as a threat to American society.

The Jewish community adopted various methods to combat Klan propaganda. The editor of the (established 1921, Indianapolis) advocated “silent contempt”; a B’nai B’rith lodge favored exposing Klan businessmen and voting against Klan candidates; the Jewish Federation promoted Americanization programs. Rabbi Feuerlicht became the community’s principal and most vocal anti-Klan spokesman.

By the 1940s any existing anti-Semitism was rather discreet, although some Jewish leaders attributed anti-Semitism to Jewish economic mobility and affiliations with socialist or liberal organizations. During the 1950s Jews established ties with local organizations to promote civil liberties and interfaith cooperation. Incidents of anti-Semitism, sparked by the (JCRC) challenge of religious practices in city schools and Christmas displays on public property, continued in the 1960s and 1970s. In recent years JCRC and the Indiana Anti-Defamation League have combated anti-Semitism through public education programs.

Within the contemporary Indianapolis Jewish community, the diverse groups are held together by common aspects of Jewish American life. There has been a drastic decline in the use of Yiddish and Ladino and a high rate of intermarriage with non-Jews. These factors have helped to diminish cultural boundaries within the Jewish community and to stimulate the replacement of social institutions unique to each group in favor of organizations that serve the total Jewish community.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.