Militant opposition to slavery was not widespread in Indianapolis because of the city’s large southern population and general race prejudice. Antislavery sentiments were evident, however, among various groups and organizations, supported primarily by New Englanders, Quakers, and reform-minded individuals.

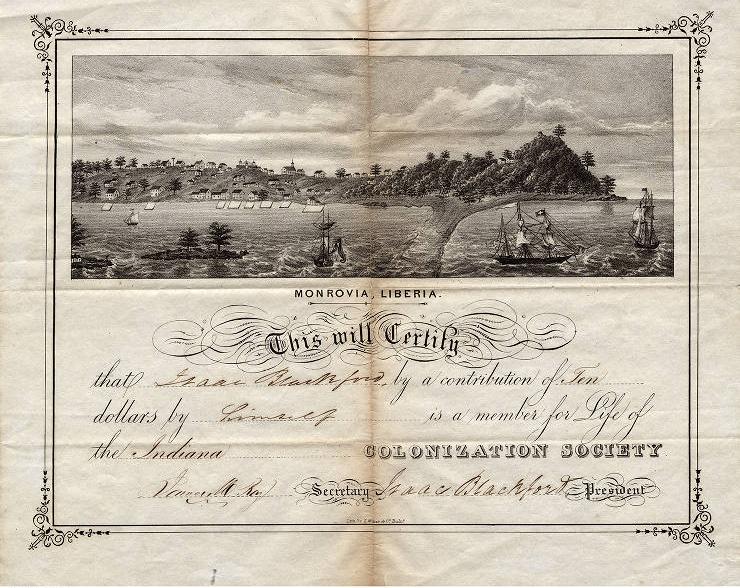

On November 4, 1829, the Indiana Colonization Society was established in Indianapolis. Its principal objective was to colonize free African Americans in Liberia. Society officers were prominent civic leaders, including state Supreme Court judges , , and James Scott, attorney , state treasurer , and county clerk . Although acknowledging that slavery was evil, the society believed that Indiana had to protect itself from a massive influx of indigent African Americans. Colonization, it believed, was the best way to protect free Blacks and to elevate their conditions.

The society held regular meetings and often raised funds around July 4th to support colonization efforts. Few local African Americans ever accepted the offer to relocate to Africa. In January 1842, free Blacks in Indianapolis held a meeting at the to declare their opposition to colonization efforts.

The debate over slavery permeated the city’s religious community. In 1840, the Presbytery of Indianapolis encouraged its clergy to deliver at least one antislavery sermon annually. The Reverend of was initially reluctant to preach against slavery among influential proslavery parishioners and residents. After learning about violence committed against African Americans and abolition sympathizers in the capital city, however, Beecher declared in a May 1843, sermon that slavery was a moral evil and that personal liberty should be extended to all people. Three years later several members left the congregation after Beecher delivered two antislavery sermons.

Other churches experienced disruptions and divisions as well. Among the Disciples of Christ, founder Alexander Campbell advised against Christians’ involvement in the slavery debate. a local Disciple, disagreed, claiming that slavery violated the universal brotherhood of man. At , Reverend James Simmons preached emancipation in the late 1850s and later attributed the burning of his church on January 27, 1861, to his opponents.

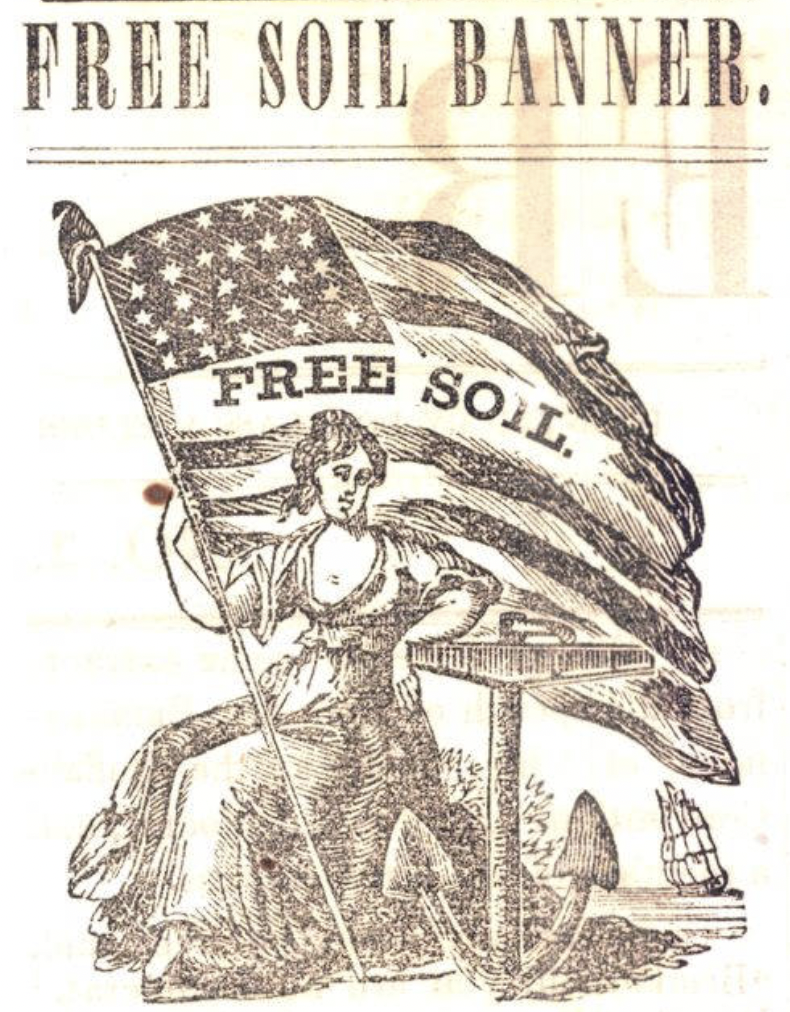

In 1848, many local citizens, including the prominent Calvin Fletcher, supported the new Free Soil Party that opposed the expansion of slavery into western territories previously held by Mexico. Indianapolis hosted a “Free Territory” state convention on July 26. Free Soilers also met on August 30 to ratify the party’s nominees and to establish the , an Indianapolis newspaper supported by Butler and edited by William Greer and from 1848 to 1854.

Other antislavery newspapers, namely the , , and , appeared in the city but were short-lived. Reflecting the public’s antipathy to African Americans, the state constitutional convention, meeting in Indianapolis in October 1850, drafted a proposal to prevent the migration of Blacks and mulattoes into Indiana. Voters overwhelmingly approved it in a statewide referendum; Marion County voted 2,509 to 308 in favor of the proposal. The measure subsequently became Article 13 of the 1851 constitution.

Numerous antislavery groups met in Indianapolis during the 1850s and contributed to growing divisions among local citizens. Christian antislavery and political Free Soilers met May 28-29, 1851, to support repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law. In February 1852, the Indiana Colonization Society encouraged increased state appropriations for its relocation program. Free Soil advocates, led by Ovid Butler, founded the Free Democratic Association on January 12, 1853, and established the newspaper to promote their cause.

Over 5,000 state delegates attended a convention at the State House in July 1855, where they adopted resolutions opposing the extension of slavery and repudiating the . Citizens also joined a local branch of the Kansas State Central Aid Committee to provide financial assistance to free-soil settlers in Kansas. In January 1857, local groups sponsored a visit by international peace advocate Elihu Burritt, who presented his plans for freeing enslaved persons.

Local groups eventually acknowledged slavery as the principal cause of both the and political division within the state. Democrats, who considered Lincoln’s preliminary Emancipation Proclamation (September 1862) to be “unconstitutional and unwise,” swept state offices in the fall 1862 elections. Pro-Union Republicans, however, retained Marion County offices and congressional seats. Local Republicans first considered emancipation to be “a measure of military necessity” to cripple the rebellion.

By the end of 1863, however, many residents invoked moral and humanitarian arguments favoring freedom for enslaved persons and a lasting peace in the nation. On January 3, 1865, local African Americans celebrated the anniversary of emancipation by parading with banners, flags, and a band through the streets of Indianapolis. Nearly 1,500 participated in a similar parade on January 1, 1866.

FURTHER READING

- Crenshaw, Gwendolyn J. “Bury Me in a Free Land” : The Abolitionist Movement in Indiana, 1816-1865 : The Catalog. Indiana Historical Bureau, 1986. https://search.worldcat.org/en/title/13222432.

CITE THIS ENTRY

APA:

Vanderstel, D. G. (2021). Antislavery Movement. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Retrieved Mar 3, 2026, from https://indyencyclopedia.org/antislavery-movement/.

MLA:

Vanderstel, David G. “Antislavery Movement.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021, https://indyencyclopedia.org/antislavery-movement/. Accessed 3 Mar 2026.

Chicago:

Vanderstel, David G. “Antislavery Movement.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2021. Accessed Mar 3, 2026. https://indyencyclopedia.org/antislavery-movement/.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.