The Twenty-eighth Regiment U.S. Colored Troops was the only African American regiment raised in Indiana to serve in the Union army during the Civil War.

Until Congress passed the Militia Act in the summer of 1862, U.S. law prohibited African Americans from serving in the military. During the era many white Northerners, including Hoosiers, opposed marching side-by-side with armed Black men, whom they deemed inferior.

Opinion began to change with the poor showing of Union forces on the battlefield. Disillusioned and war-weary, many white men feared the emergence of a national draft. When President Abraham Lincoln called for 300,000 volunteers in October 1863, Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton sought to meet Indiana’s 16,000-man quota, in part, by recruiting African Americans. In November 1863, the U.S. War Department authorized Governor Morton to raise one regiment of African American infantry.

Newspapers like the published pieces appealing to Black Hoosiers to fight so their “suffering brethren” in the South could obtain a higher degree of freedom like Black Northerners. Some African Americans enlisted with the hope that demonstrating loyalty to the Union and proving themselves on the battlefield would result in full citizenship. Chaplain Garland White, who escaped enslavement in Virginia and served as the Twenty-eighth Regiment’s only African American officer, hoped that military service would result in “freemen at the ballot box, as at the cartridge box.” Others were attracted by the federal government’s $300 bounty for enlistment.

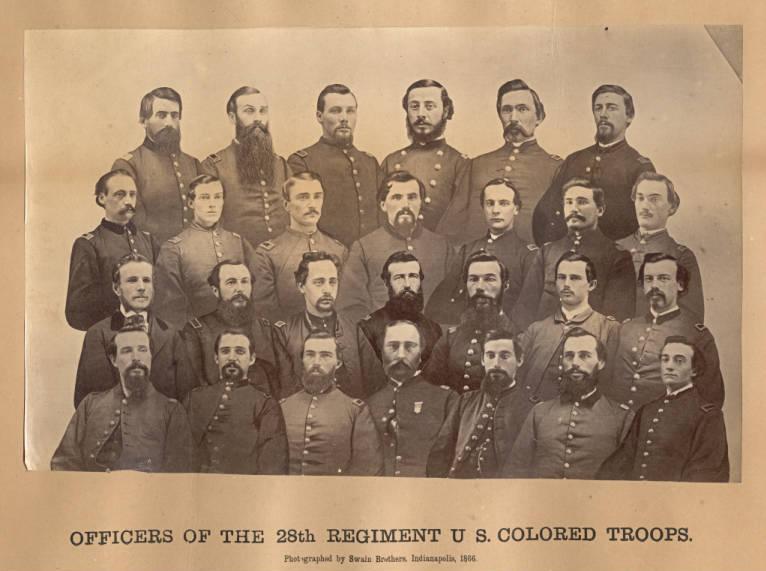

Prominent Indianapolis lawyer and abolitionist and Reverend , pastor of the , helped recruit Indiana’s only Black regiment. Six companies were raised, comprised of approximately 518 men. These volunteers, from Indiana and other states, like New York and Connecticut, listed occupations such as farmers, barbers, and masons.

From December 1863 to April 1864, they organized and trained at Camp Frémont, near Fountain Square, on farmland donated by Fletcher. Rather than receive military pay, they were compensated as laborers working for the Army. Until Congress ordered equal pay and rations in June 1864, Black soldiers lacked adequate equipment, uniforms, and rations, humiliating them and hindering their effectiveness.

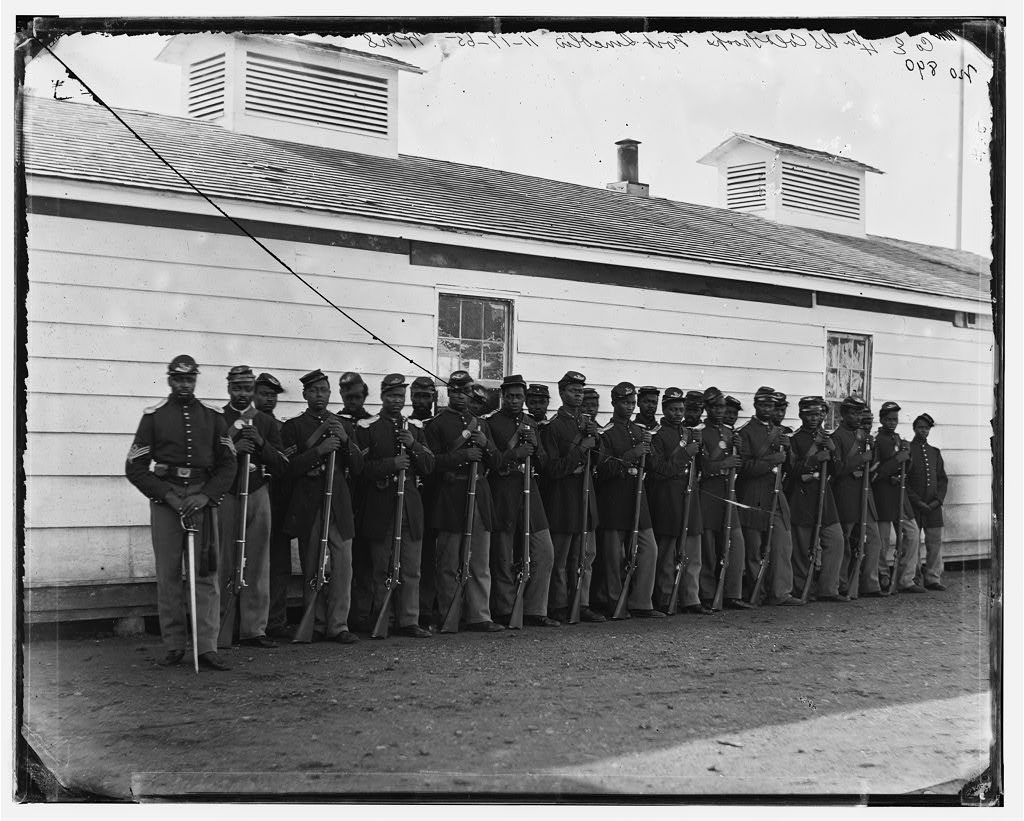

Indiana’s African American companies, designated the Twenty-eighth Regiment U.S. Colored Troops, departed Indianapolis in April 1864 for Washington, D.C., before traveling to Camp Casey, near Alexandria, Virginia, for additional training. More companies were raised in July, and by war’s end approximately 1,600 men served in the regiment. The Twenty-eighth was assigned to the Fourth Division of the Ninth Army Corps, commanded by General Ambrose Burnside.

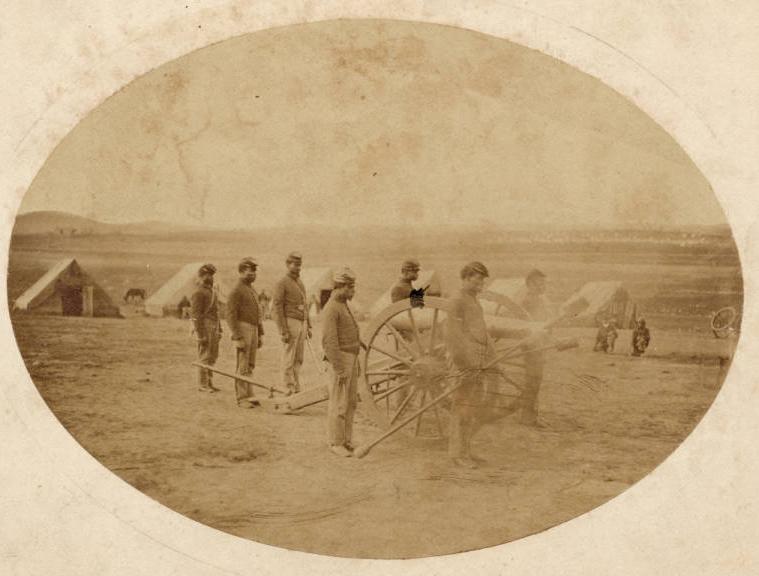

Between summer 1864 and spring 1865, the regiment engaged in the Siege of Petersburg, which was necessary to capture the Confederate capital in Richmond. As part of this siege, the regiment fought in the ill-fated Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864. In order to clear a path to Richmond, Union leaders devised a unique plan to establish a mine underneath Confederate fortification. Troops would dig a tunnel, lay and detonate explosives, and then advance on shocked Confederate troops in the middle of the night.

The plan proved disastrous when, as Chaplain White noted, “This grand convulsion sent both soil and souls to inhabit the air.” In the melee, Union troops ran into the crater, rather than around it, encountering devastating counterattacks. The Twenty-Eight Regiment entered the battlefield in the second advance. Like their white counterparts, some tried to fight, while others fled. Unlike their white counterparts, some Confederate soldiers killed African American soldiers trying to surrender, as well as those taken captive. General Burnside testified that some of the Twenty-eighth soldiers “held the pits behind which they had advanced, severely checking the enemy until they were nearly all killed. I believe that no raw troops could have been expected to have behaved better.” After the battle, four additional companies joined the devastated regiment.

When Petersburg fell, the Twenty-eighth, reassigned to the Army of the James, were some of the first troops to enter and take possession of Richmond in early April 1865. Chaplain White recalled that when the troops entered the city “the doors of all the slave pens were thrown open, and thousands came out shouting and praising God.”

The Twenty-eighth Regiment then traveled to City Point, Virginia, where they guarded Confederate POWs, infuriated by being overseen by African American men. The Twenty-eighth was stationed in Corpus Christi, Texas, and mustered out on November 8, 1865. The soldiers returned to Indianapolis in January 1866, where they were honored with a parade and public reception.

Approximately 186,017 African Americans served in the Union army, the majority of whom were from Confederate states. Like these men, Hoosier troops soon realized that their hope for equal citizenship and rights would remain unfulfilled, despite their service.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.