Photo info ...

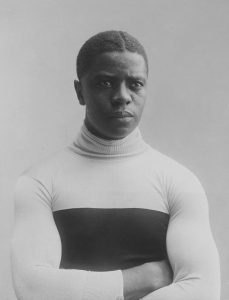

Pictured: Major Taylor, 1906-1907Credit: Jules Beau, Public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsView Source

(Nov. 26, 1878-June 21, 1932). Born into poverty in rural Marion County, Indiana, Major Taylor became one of his generation’s wealthiest and most famous athletes.

Taylor’s father, Gilbert, was a Civil War veteran and worked as a coachman for the Albert Burley and Laura (Brouse) Southard family of Indianapolis. Southard was superintendent of the Indianapolis Peru & Chicago Railroad. His son Daniel was born the same year as Taylor, and the two reportedly were friends for the rest of their lives. As a companion for young Daniel Southard, Marshall received many benefits not normally accorded a Black child in his era, such as a semiformal education and his own bicycle.

Taylor’s skill on his bike earned him a dollar-a-day job as a trick rider for the local Hay and Willits bicycle shop. The military-style uniform provided for the position gained him the nickname “Major.” He competed in his first bicycle race in 1890.

At the age of 14, Taylor defeated a top amateur field in a 10-mile road race. On June 30, 1895, he won a professional 75-mile road race between Indianapolis and Matthews, Indiana. He then set several unofficial records at Indianapolis’ Capital City bike track in August 1896. Such feats resulted in numerous death threats, and Indianapolis tracks were subsequently restricted to white individuals only.

Seeking greater racing opportunities, Taylor and his mentor, Louis (Birdie) Munger of Indianapolis’ Munger Bicycle Company, moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1896. Over the following decade, Major Taylor established world bicycle racing records for seven different distances. He reigned as American Champion in 1898, and as World One-Mile Sprint Champion in 1899. An 1898 race at Indianapolis’ drew over 18,000 fans. A 1901 barnstorming tour of Europe produced 42 victories in 57 races against the continental champions. He became the first African American to become a world champion in cycling or any other sport.

Racing before admiring throngs throughout Europe and Australia between 1902 and 1909, Taylor earned as much as $35,000 annually (around $1 million in 2020). Taylor, his wife, Daisy, and daughter, Sydney, traveled first class on great French and German steamships, stayed in elegant continental hotels, and dined at the world’s finest restaurants. In an era when baseball, prizefighting, and bicycle racing vied for America’s attention, Taylor dominated the world’s sports pages.

In the United States, Taylor faced constant racial harassment and discrimination. He was often prohibited from racing on American tracks. In cities where he was allowed to race, he had difficulty finding accommodations. Though widely admired for the religious devotion inspired by his mother, Saphronia, Taylor endured racist cycling organizations, his rivals’ physical assaults, and self-serving promoters. Extreme exhaustion led to his retirement in 1910.

Little is known of Taylor’s post-retirement years. He lost $15,000 in the failed manufacture of a patented automobile wheel prior to World War I. Bad investments, the financial failure of his 1928 autobiography, , a 1930 divorce from Daisy, and chronic heart disease left him penniless.

Moving from Worcester to Chicago in 1930, he took up residence at the South Wabash Avenue YMCA. In 1932, Taylor died in the charity ward of Cook County Hospital and was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave. In 1948, Frank Schwinn of the Schwinn Bicycle Company provided a private grave and tombstone for the fallen hero. His connection with Indianapolis has been commemorated with the naming of the Major Taylor Velodrome track, part of the larger Indy Cycloplex campus.

A historical marker was erected in honor of Taylor on August 13, 2009. The , Central Indiana Bicycling Association Foundation, and the Indiana State Fair Commission erected the marker along the Monon Trail near the pedestrian and bike bridge over East 38th Street near the .

In September 2020, the city of Indianapolis and the announced the “Bicentennial Legends,” a series of murals that will honor Indianapolis’ historical icons. The Arts Council selected artist Shawn Michael Warren to create the mural of Marshall “Major” Taylor, identified as the first mural subject in partnership with the Major Taylor Coalition, an informal group of Central Indiana residents dedicated to honoring Taylor. The mural is at the corner of Meridian and Washington streets.

Documentary filmmaker Cyrille Vincent started production on a film titled Whirlwind in 2023. The film aims to chronicle Taylor’s life and his lasting influence on the world of cycling.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.