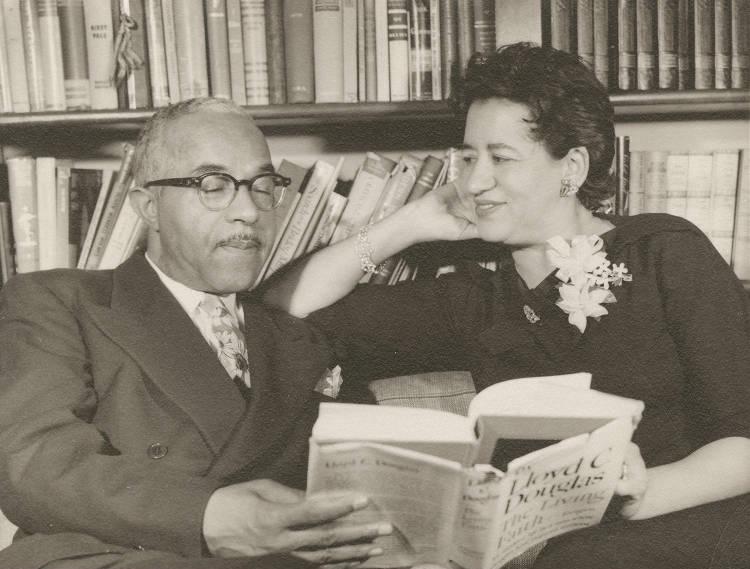

(Aug. 23, 1913-July 8, 2005). African American equal rights activist Roselyn Comer Richardson was born in Roberta, Georgia, in 1913. After graduating from Fort Valley Normal and Industrial School, she attended Atlanta’s Clark College from 1930 to 1934. Richardson then studied community organization and group work at the Atlanta University School of Social Work.

This training served her well when in 1936 she was hired as Southern Field Secretary for the Quaker organization, Emergency Peace Campaign. The group advocated for international peace in response to the emerging conflict that would culminate in World War II. Two years later, she moved to Indianapolis after marrying prominent African American attorney and state legislator , with whom she would often partner in her work for civil rights.

According to the , Richardson found Indianapolis to be more segregated than Atlanta, stating, “There were stores downtown where a Black person couldn’t even try clothes on.” She was determined to change this and challenged discrimination in public spaces, such as drugstores and tea rooms.

For most of her life, Richardson held various unpaid leadership positions with local political, educational, and civic organizations, including the , Flanner Guild, , and , which her husband helped establish.

Perhaps Richardson’s most enduring accomplishment in fighting discrimination resulted from the neighborhood school’s (IPS School No. 43) refusal to admit her six-year-old son in 1947. Richardson and another mother, Willa Taylor, unsuccessfully appealed to the (IPS) superintendent to admit their children. Following the superintendent’s decision, Richardson recalled, “We started fighting for integrated schools right then and there…. We called neighborhood meetings and started running around town organizing Black people.”

After mobilizing the local Black community, Richardson convinced her husband, who feared the time was not right to challenge school segregation, to advocate for equal educational opportunities. Drawing on his experience as a legislator, Henry Richardson helped write a school desegregation bill and successfully lobbied for its passing in 1949. Although IPS maintained segregation by reestablishing elementary school boundaries, the Richardsons laid the groundwork for full desegregation in Indianapolis and challenged school segregation five years before the U.S. landmark case Brown v. Board of Education.

In addition to education, Roselyn Richardson strove to open job opportunities to African Americans in her work with the Association for Merit Employment. In a July 31, 1979, article, she stated, “about the only Blacks you saw in public places 20 years ago were running elevators, waiting tables or doing janitor work…. It wasn’t that Blacks couldn’t do other jobs. It was just that they had never been given the chance.” Similarly, in her prolific work with IPS parent-teacher associations, Roselyn organized the Pupil Motivation Committee. The committee worked to connect students with role models who had achieved career success. In the 1970s, Roselyn organized and directed the Career Sampling Program at Shortridge, in which companies like and Bicycle Repair Shop recruited students to sample jobs.

After her husband’s death in 1983, Richardson founded the Friends of the Indianapolis Urban League, which supported the league’s activities. She also joined Dialogue Today, a club comprised of Jewish and African American women who discussed racial issues. Richardson died in 2005, and, while her husband has rightfully received praise for his activism, Roselyn Richardson’s often-forgotten organizational skills and tenacity were instrumental in making Indianapolis a more equitable city.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.