The American Civil War accelerated the transformation of Indianapolis into a major industrial city. As the seat of state government and key railroad hub of Indiana during the war, important war-related services and businesses that gravitated to the city fueled its rapid growth.

From the beginning of hostilities in April 1861, Indianapolis served as the chief troop-mobilization site for military forces raised in the state. Within hours of the news arriving of the attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina that commenced the armed rebellion of the Confederate states, the Indiana state government began to organize volunteer troops in the city. Within two weeks, Indiana’s first 12,000 volunteer soldiers converged on Indianapolis.

The state had no camps, no weapons, and no supplies. Indiana Governor summoned , who had served in the and later wrote , and appointed him adjutant general. An arsenal was set in a rented building on the grounds.

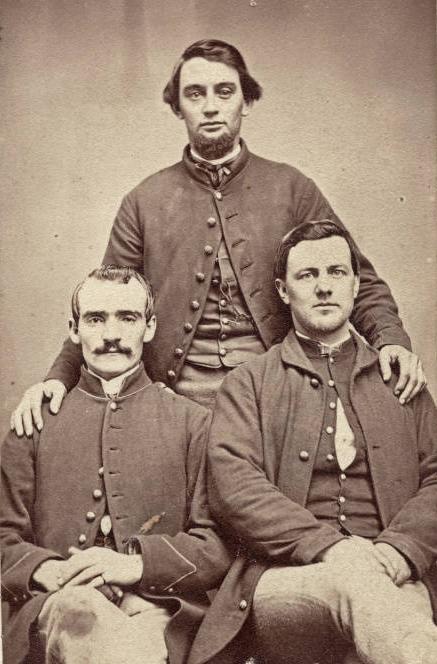

Participants in the Conflict

In the early months of the war and during subsequent periods of almost frantic efforts to raise volunteer troops, Indianapolis accommodated thousands of Union soldiers at any one time.

With President Abraham Lincoln’s first call for volunteers, six infantry regiments were organized in Indianapolis. The six regimental commanders included one West Point graduate and five lawyers. One of the lawyers was , who later became a U.S. Congressman.

Four units had been headquartered in Indianapolis before the war, and all four mustered into the 11th Volunteer Regiment. One of the militia lieutenants was , later the highest-ranking officer in the Union army. Another militia officer, Francis A. Shoup, a West Pointer and a lawyer, switched to the side of the South. He served as a brigadier general in the Confederate army. Private John C. Hollenbeck was the first Indianapolis resident killed in the conflict. He died on June 27, 1861, near Romney, Virginia.

Prominent received permission from Governor Oliver P. Morton in 1861 to establish the 32nd (First German) Regiment, commanded by General August Willich, which served with distinction at Shiloh and Missionary Ridge. The Germans’ role in the Civil War was indicative of their relationship with their new country. Germans believed that, since the United States was still in its formative stage, they had a particular role in infusing the best of their own cultural and intellectual traditions into the American mainstream. During the conflict, the Indianapolis German community actively opposed slavery, favored the Union, and volunteered in large numbers to fight for the new fatherland. German societies, led by the , not only promoted German language and culture but also liberal politics and social issues, such as abolition and workers’ rights, and advocated the need to oppose the Confederacy.

The also quickly responded to the call for volunteers. They raised an Irish regiment (the 35th ), commanded by Colonel John Walker of La Porte, and used St. John’s parish school, located at 124 West Georgia Street, as a recruiting station. The regiment was later consolidated with the 61st or Second Irish Regiment. Members of the Irish Republican (or Fenian) Brotherhood, a national organization founded in 1857 and dedicated to a free Ireland, saw the war as an opportunity for Irishmen to gain military experience for their forthcoming confrontation with Great Britain.

In fall 1862, during a rush to organize new regiments to repel Confederate armies in Kentucky that menaced both Indiana and Ohio, more than ten thousand volunteers packed the training camps around Indianapolis. The army commander in the city staged a huge mock battle as a training exercise preparatory to the troops boarding southbound trains. Indeed, during the July 1863 raid of Confederate cavalry General John Hunt Morgan into Indiana, tens of thousands of Indiana citizens rallied to repel the invader, turning Indianapolis into one large military camp.

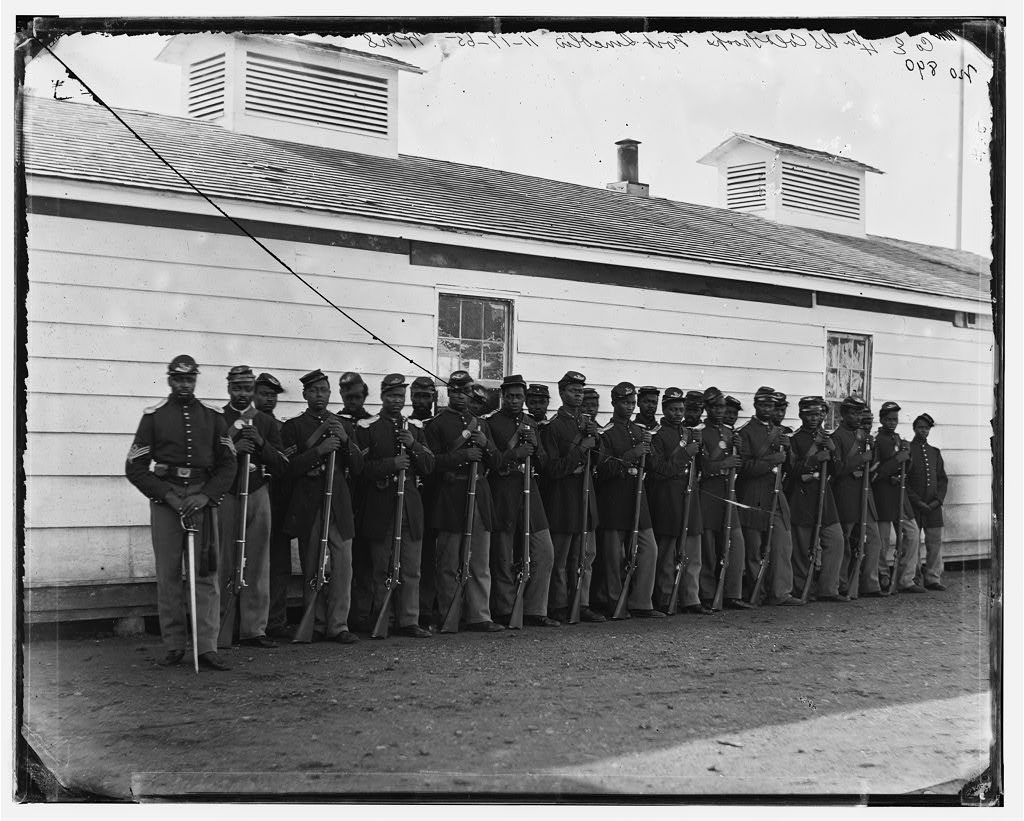

The , the only Indiana Black Civil War regiment, enrolled at Camp Fremont, near . The regiment mustered in for three years on March 31, 1864, and lost 212 men in their cause. A full company of 100 men had previously volunteered with the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, another all-Black unit.

The favorite regiment of Indianapolis citizens was the 132nd Infantry, proudly referred to as “The City Regiment”. Made up of young boys and old men, the 132nd was organized in May 1864, to serve for 100 days as railroad guards in Tennessee and Alabama. The largest crowd ever assembled in Indianapolis to witness a regiment’s departure escorted the 132nd to the depot. Twelve of the men died of disease before the regiment returned.

Late in the war, as commanders pressed all available troops into the armies, the city hosted fewer troops. As Indiana regiments returned home either on furlough or to muster out of service, Governor Moton paraded and feted each unit as it passed through the city.

It is estimated that 4,000 Indianapolis men served in the war and that 700 of them died during the conflict.

The Homefront

State and federal authorities created numerous camps and installations in and around the state capital to gather, train, equip, and send forth infantry, cavalry, and artillery units to suppress the rebellion. As the war progressed and federal troops captured significant numbers of rebels, the need arose for facilities to incarcerate prisoners. In February 1862, , which had served as the , began as a rendezvous camp for volunteers and was refitted as a prisoner-of-war camp. In a matter of days, prisoners started arriving. A palisade wall, with reinforced gates and sentry stations, surrounded Camp Morton. By the end of February, about 3,000 prisoners were incarcerated in the prison. Another 1,000 arrived in early April. Many were sent on to Lafayette and Terre Haute.

Residents responded immediately to the prisoners’ needs. A hospital was improvised in the Athenaeum at Maryland and Meridian Streets. The citizens donated food, blankets, and $5,400. The War Department took over the management of the camp. By late 1862, most Confederate prisoners-of-war in Camp Morton had been shipped south as part of prisoner exchanges, leaving it mostly empty. However, in 1863 Union victories in the West led to the camp to refill.

Despite the efforts of Camp Morton officers, prisoners died in large numbers, especially when the exchange cartel broke down when Confederate authorities refused to treat captured African Americans as prisoners of war. Crowded camps became increasingly crowded. In May 1864, as a negotiation tactic, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton cut the prisoners’ daily ration. In early 1865 the prisoner exchanges resumed. The last Camp Morton prisoner was released on June 12, 1865.

Camp Morton had the highest mortality statistics of the camps administered by the War Department. Historians point to three factors in Camp Morton’s mortality numbers, from which all the camps suffered: overcrowding, rampant disease among the prisoners, and lack of medical knowledge among medical staff. Pneumonia was the chief killer, followed by diarrhea/dysentery, and malaria. Disease spread readily in the crowded barracks, which had dirt floors. Water supplies became polluted by sewage.

The presence of thousands of soldiers in Indianapolis had both good and bad effects. Drunken soldiers roamed city streets, frequenting saloons and brothels that popped up to accommodate troops far from home. Street fights broke out, some involving armed standoffs between soldiers and city police. Residents complained of property destruction caused by rowdy soldiers. Troops and local civilians did not always see eye to eye politically, causing tensions and not infrequent barroom brawls, shootings, and other encounters. Soldiers grew resentful and intolerant of Democrats who opposed the war of coercion waged against Confederate rebels.

In August 1861, soldiers threatened to attack the offices of the Indianapolis , the chief Democratic newspaper in Indiana. Later, the so-called “,” in the aftermath of the Democratic state convention on May 20, 1863, featured an armed confrontation between troops and citizens. Military officers posted artillery in intersections and cavalry squads patrolled the streets. The city’s small police force was powerless to handle either side. In 1864 Democrats also claimed troops posted in the city intimidated voters at the polls.

Officers and enlisted men from the army camps patronized the city’s hotels, restaurants, theaters, and concert halls. Merchants sold their wares, and residents rented out their spare rooms to boarders. War-related economic activities flourished as city merchants secured contracts to equip, clothe, house, and feed the troops in the city. Indianapolis prospered from the war.

The key reason for the prosperity was the network of that coursed through the city. The first railroad to serve the state capital, the Madison and Indianapolis line, was completed in 1847. In the following decade, several other lines connected Indianapolis to points in all directions. The railroads facilitated the transport of people, livestock, agricultural commodities, and manufactured goods to and from the city to meet war demand.

Industrialists located factories in the city to take advantage of efficient transportation facilities. A chief example was the wartime arrival of , an Irish meatpacking firm eager to secure military contracts to feed Union armies. Hundreds of Kingan workers slaughtered and packed hogs driven to the city by trains, which then carried barrels of pork to the fronts. Mills ground grain into flour for military consumption, and blacksmith shops and ironworks produced agricultural implements and railroad equipment.

Indianapolis also became recognized nationally for the care it provided servicemen and their families. The federal administration took over the City Hospital, and over a two-year period, it provided care for 6,114 patients, 847 of whom were prisoners. A Soldiers’ Home was built at West and Maryland streets to provide a place of relaxation for soldiers passing through Indianapolis. The home became the largest in the Midwest and accommodated 8,000 for meals and 1,800 for shelter. A Ladies’ Home was built, convenient to , for needy wives and children of Civil War soldiers.

As a result of increased economic activity, the city’s population grew rapidly. The 1860 federal population census recorded 18,600 residents in Indianapolis; in 1870, the city’s population had risen to 48,200. The number of African American residents increased from 498 to 2931, and foreign-born residents increased to over ten thousand. Women, often wives and/or daughters of soldiers, flocked to the city from rural areas to work in war-related enterprises. They sewed uniforms in workshops or by piece work in their homes, while others made gunpowder and cartridges in the state arsenal.

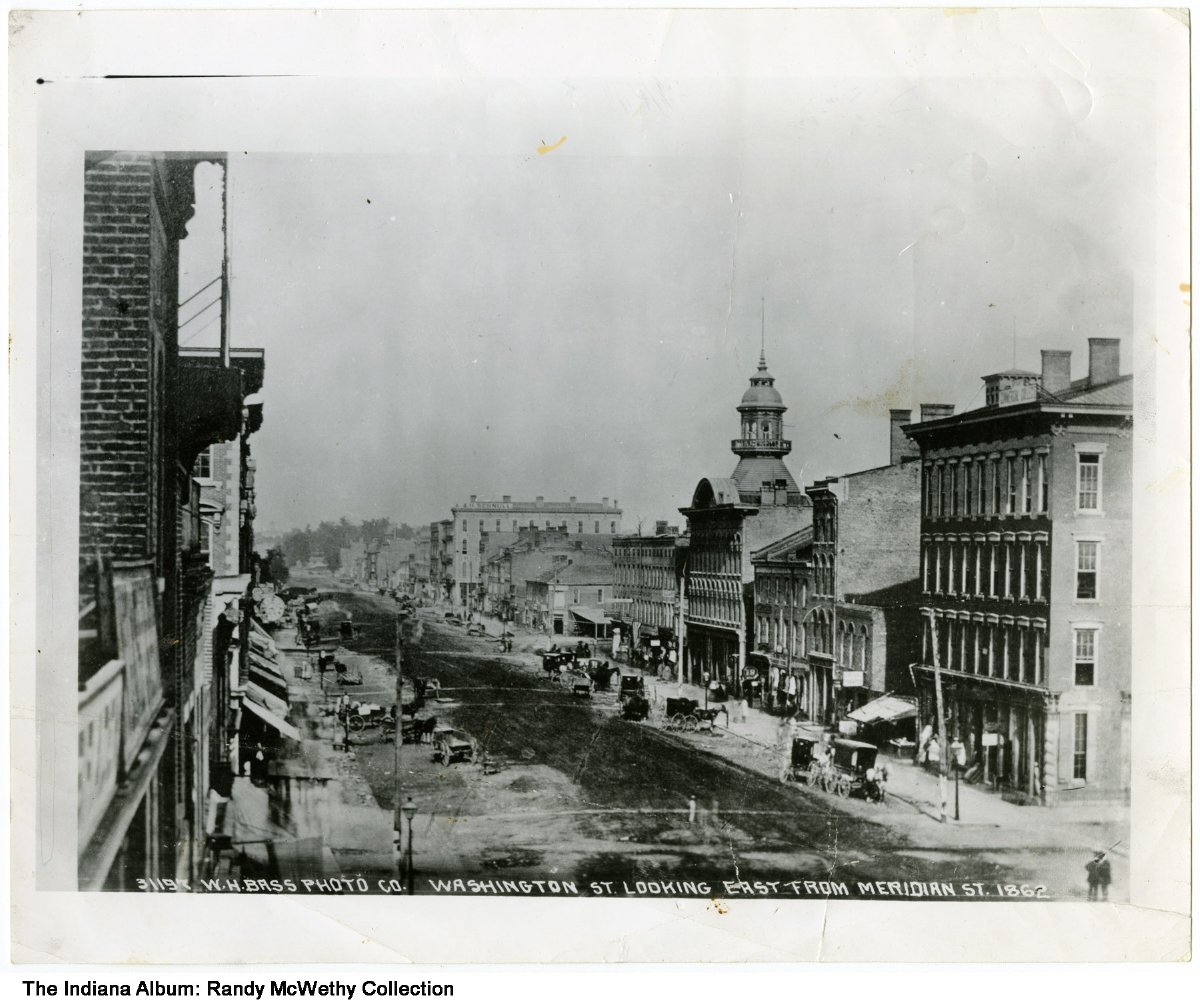

The growth in population created a demand for housing, which was in short supply during the war years. House construction brought builders and related workers to Indianapolis. Population growth in the capital city outstripped that of Evansville, New Albany, and Terre Haute, other state population centers, during this period. In 1864 investors established a horse-drawn rail trolley network to connect residential to business areas. In that same year, entrepreneurs failed to navigate by steamboat, the last attempt to supply the metropolis cheaply by waterway. During the war and thereafter, the concentration of manufacturing and other capital investment in Indianapolis established the city as Indiana’s business and population center.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.