Roberts Settlement was an African American settlement in western Jackson Township in Hamilton County. The remains of the settlement, a chapel, and cemetery, are 30 miles north of Indianapolis just to the east of U.S. 31 on 276th Street in Hamilton County. At its peak in the 1870s, 300 residents lived on over 1,500 acres of African American-owned land.

Established in 1835, its founders built an economically and socially independent community that flourished into the late-19th century and remained vibrant for decades thereafter. The neighborhood’s accomplishments were extraordinary given the racial discrimination and disadvantages imposed upon all African Americans.

Roberts pioneers were free people of combined European, African, and Native American descent. Most were members of families that had intermarried and lived near one another in North Carolina from the mid-18th century. They migrated to Indiana’s frontier in response to declining farm opportunities and increasing restrictions on their rights as free people of color.

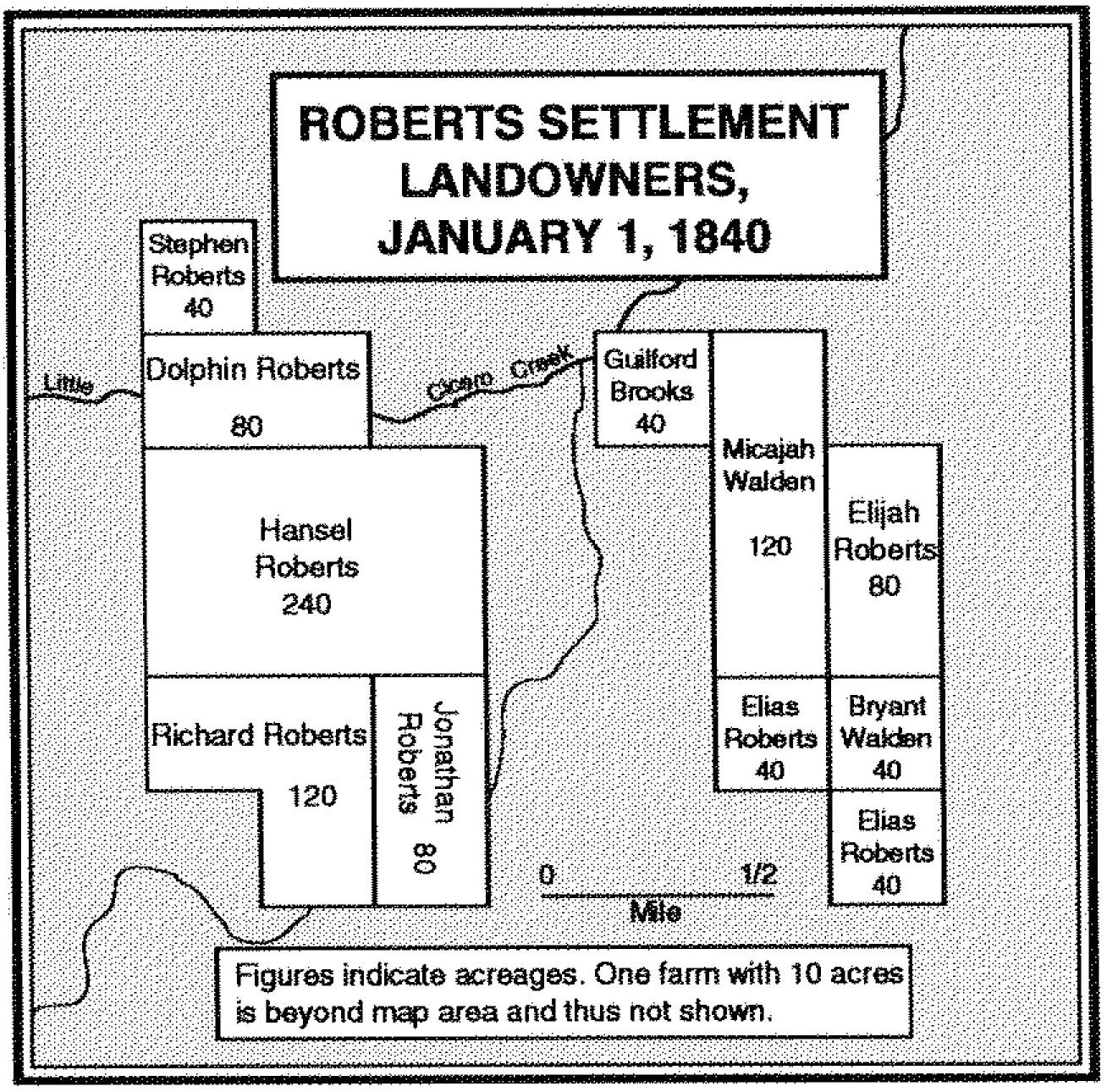

In July 1835 Hansel Roberts, Elijah Roberts, and Micajah Walden purchased Roberts Settlement’s first land. A few months previous they and their families had settled on their claims. Their choice of location had been intentional: Quakers and other tolerant whites lived to their south and southwest. As the area’s prospects grew more certain, other kin joined the first families. By 1840 about 75 residents lived on 930 acres of African American-owned land.

With landownership and cordial neighbors as their bedrock, community members built strong community institutions. A Methodist congregation soon formed, and a meetinghouse was built near the neighborhood’s center. In the 1840s the group converted to Wesleyan Methodism, a then-radical faith that attacked slavery and championed racial equality. For nearly a century thereafter monthly Wesleyan circuit meetings brought Roberts residents and neighboring white co-religionists together on racially equal terms rare at the time.

Settlement leaders also quickly provided their children with formal educations. Prior to the a subscription school was held at the meetinghouse. Shortly after the Civil War, a public schoolhouse was built nearby. Residents supervised and taught its class sessions. In the 1880s, Roberts Settlement children were among the first to attend the area’s first high school. At least six graduated from post-secondary schools before 1900.

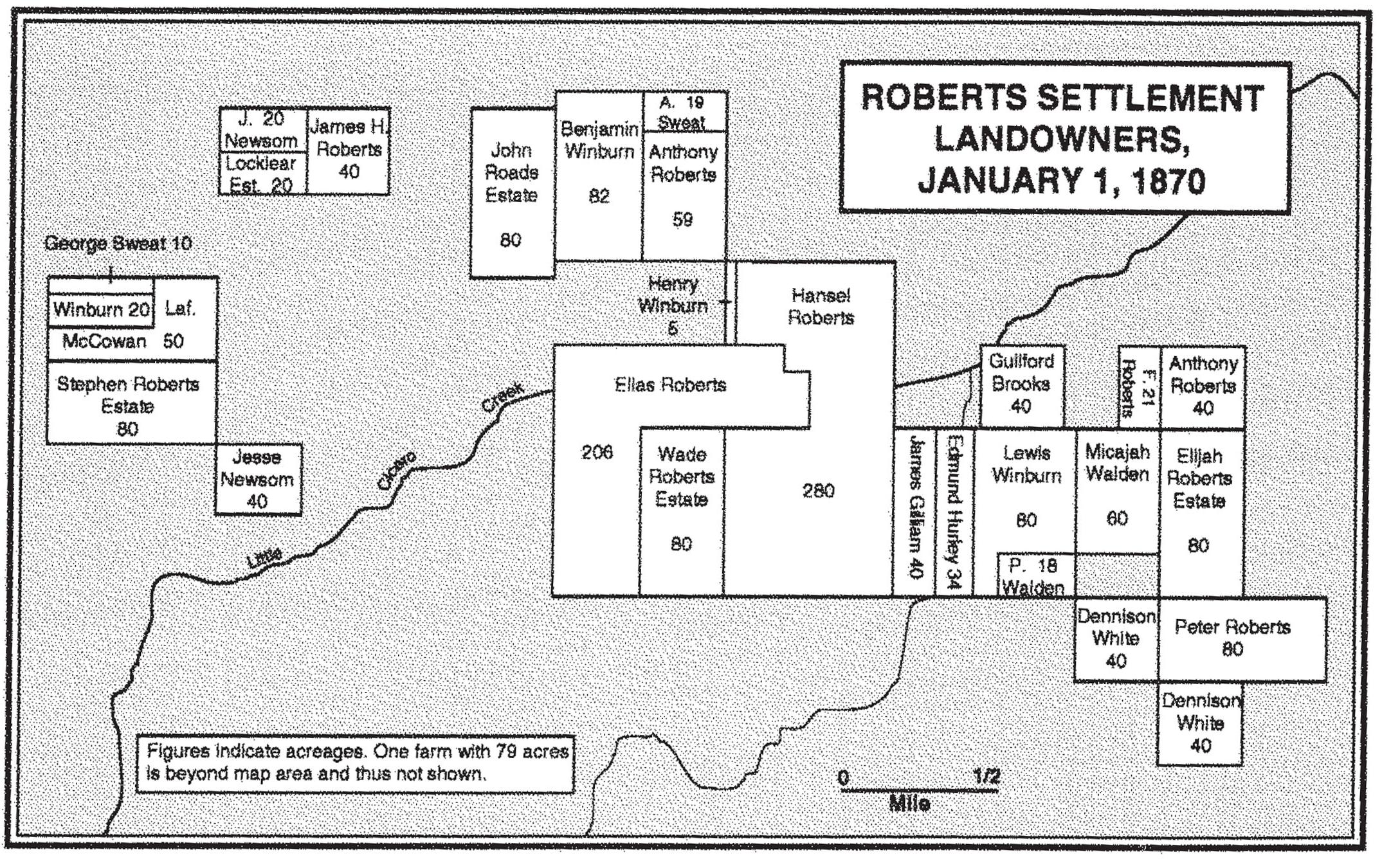

Roberts Settlement’s economic and demographic trajectories paralleled those of surrounding white farm communities. In the 1850s and 1860s, Roberts Settlement farmers prospered with the arrival of railroad transport, horse-powered machinery, and high Civil War grain prices. Improving conditions, in turn, allowed larger farmers to expand their holdings and encouraged raising large families. By the early 1870s, 300 residents lived on farms totaling 1,743 acres.

The neighborhood’s prospects diminished from the late-19th century. Declining livestock and grain prices, together with farm consolidation, led to challenging times and reduced landholdings. Outmigration grew apace, especially among Roberts’ younger members. By 1900 Robert Settlement’s population had declined to 150. Over the two generations thereafter the Roberts school closed, and the church’s Wesleyan affiliation ended. The last permanent residents passed away in the early-21st century.

Those leaving Roberts Settlements often became ministers, teachers, and professionals in other areas. Their ranks included the Reverends Dolphin and Cyrus Roberts, African Methodist Episcopal ministers; Adora Knight, a teacher and principal in Terre Haute schools; Ira Roberts, an Iowa state judge; and Carl Roberts, a Chicago surgeon. Most others were able to find stable employment, become homeowners, and pass on a keen sense of their families’ heritage to their children.

Far more than most African Americans during the slave and Jim Crow eras, Roberts Settlements members and descendants were able to shape their own destiny. They did so with remarkable results.

In 1925, descendants of Roberts Settlement residents organized a gathering at the Roberts Chapel grounds to celebrate the cultural heritage of the place and to renew family relationships and friendships. The Roberts Settlement Homecoming has become a tradition, held annually on July 4th weekend.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.