On July 15, 1856, the newly formed Republican party held its first convention in Indianapolis. Delegates and friends began with a parade down Washington Street (see ) to the , highlighted by a group of young men costumed as the pro-southern “Border Ruffians” who were then terrorizing the Kansas Territory. At each intersection, the performers staged tableaux illustrating different abuses undertaken by the actual Ruffians against the free state advocates and settlers of that new territory. Laughter and cheers built the crowd’s enthusiasm for the speeches and evening torchlight procession that followed. Although Republicans were narrowly defeated in the following fall election, the rally heralded the arrival of a significant political party.

The Republicans who convened in 1856 were a product of the disorderly realignment of voter allegiance that followed the passage of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act. Using a label earlier employed by the followers of Thomas Jefferson, the new party was a fusion of several followers. Some were former Whigs, who continued to speak a language of economic development that stressed government support for internal improvements and banking systems that encouraged sound money. Allied with them were free soil elements who sought, as their name suggested, the elimination of enslavement from the western territories and the passage of a Homestead Act. Present also were a variety of Protestant social reformers, some motivated by abolitionist thinking and others by hostility to the sale and consumption of alcohol. They were joined after 1856 by former members of the short-lived American, or Know-Nothing, party who favored a program of immigration restriction. However diverse and contentious they appeared, all were united by a desire to defeat the .

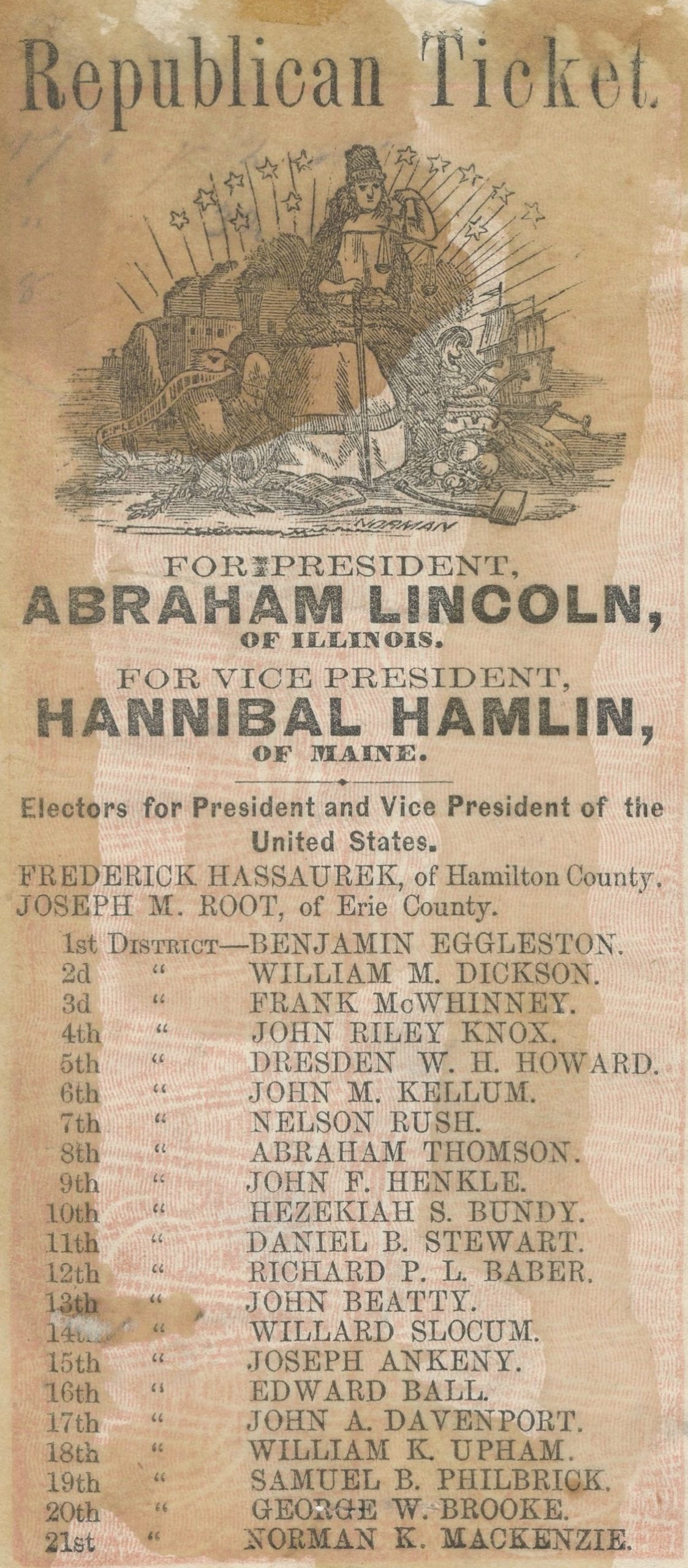

By 1860, the new party had succeeded in , helping secure the election of Abraham Lincoln while carrying local and state candidates. The party’s support for Lincoln carried over into support for the Union cause during the ensuing period of secession and war, causing some in the Republican ranks to accuse the Democrats of being Copperheads, traitors to the Union cause. Union veterans would play a prominent role in the party for many years after the war that they often called the War of the Southern Rebellion.

Many of the features present in its formative years characterized the rhetorical appeals and programmatic goals of the Republican Party for decades to come. These included emphases upon economic growth and moral reform, respect for the Union, and contempt for the Democratic opposition. Later interpreters have argued that the Republican appeals were particularly successful in attracting ethnic and religious groups whose values and beliefs emphasized personal piety and self-reliance. The diversity of the Republican support base also helps to account for a recurring party tendency to factional division.

The 19th-century party was organized primarily through campaign committees that were formed for each election. Members of the committees were generally leading party spokesmen and editors, incumbent officeholders, prospective candidates, and local organizers with proven ability to turn out voters on election day. At a time when Indiana was an intensely competitive two-party state, whose electoral vote might well decide the presidency, the national Republican Party often took an active hand in local organization, providing funds, speakers, and advisers. The nomination of of Indianapolis in 1888 and 1892 confirmed this close connection; the creation of the as a marching society for Harrison in 1888 illustrates the ad hoc nature of many early campaign activities.

The closeness of voting, particularly after a Democratic surge that began in the 1880s, caused local Republicans to seek a more formal party structure. The result was an organization composed of committeemen representing geographic subdivisions of the county called precincts. Precinct leaders often relied heavily upon present and prospective government workers, lending a strong emphasis on patronage to the formal workings of the local party. The ensuing tension between the voters’ interest in issues and candidates, and the party workers’ interest in government offices and jobs, continued well into the 20th century.

As issues began to fade, and voters with no personal memory of that conflict began to enter the electorate, the Republicans (now often styling themselves the Grand Old Party, or GOP) began to seek new appeals. Some were local initiatives, such as John Caven’s project in the 1870s. Others were national, such as the attacks upon the perceived radicalism of William Jennings Bryan in 1896. Local and national trends could come together, as they did during the Progressive Era when some Republicans championed the ideas of government efficiency and social justice identified with Theodore Roosevelt, , and other party leaders. Yet because the appeal of Progressivism ran counter to more established issues in the party, it encouraged a new factionalism that culminated in the Bull Moose division of 1912.

The key figure in reorganizing the local party to meet the electoral challenges of this situation was , who became party chairman in 1914 and mayor in 1918. A Harvard-trained lawyer, Jewett built a following among younger voters through the Republican Union. Legally unable to succeed himself as mayor, Jewett was forced to seek accommodation with the individual he had defeated for the 1917 mayoral nomination, . In 1921 Shank secured his nomination for mayor, and a year later used the distribution of city jobs to committeemen to assure the selection of his choice, William Freeman, for party chair. Shank, in turn, quickly encountered the rivalry of , county clerk and former county sheriff. Long active in party affairs, and still supported by many sheriff’s deputies, Coffin launched his bid for full control of the party in 1924, running for party chairman against Shank’s choice, Robert Miller. Their struggle led to a tense county convention marked by attempts to disqualify committeemen by court order, with large numbers of armed police loyal to Shank facing large numbers of armed deputies loyal to Coffin, before a close vote favored Coffin.

Coffin’s victory came at a time when the was bidding for power in Indiana, and Coffin had sought and received the support of the Klan. Unlike other Klan-backed leaders who quickly fell from power, Coffin retained his hold on the local party until the early 1930s. Coffin’s faction of supporters, with some changes in loyalty over time, would remain a contender for party control until the 1940s. The effects were soon felt. Coffin and his allies sought, with some success, to attract white, working-class Democrats to the Republican standard, but saw the GOP lose its traditional support in the African American community. Coffin, however, never totally controlled local Republican officeholders, and was unable to prevent an anti-Klan Republican prosecutor, William Remy, from securing indictments and convictions of several Coffin allies including mayor .

Factionalism, growing public antipathy to the Klan, the loss of the African American vote, and the onset of the during the Herbert Hoover presidency came together to defeat the Republican ticket in 1929, ushering in a fairly long period of Democratic advantage in local politics. Faced with this challenge, the local Republican Party entered a period of factionalism marked by vigorously contested county conventions and shifting personal and group alliances. Between 1930 and 1944 the party chose eight different individuals as chairman. Best remembered were probably and Henry Ostrum, who gained reputations for their emphasis on door-to-door canvassing (then called “polling “) and election day voter turnout efforts. These rebuilding activities produced results in the early 1940s as the party started to win significant local offices. victory for mayor in 1942 marked the return of the GOP as a force in local affairs.

Larger state and national concerns played significant roles in the shape of the party in that era. The Republicans often enjoyed more success carrying state and national tickets rather than local slates. The success of the GOP in capturing the State House after 1948 led to a marked interest in state, as opposed to local, patronage. The economic conservatism that flowed from resistance to the taxes and regulation associated with the Democratic New Deal caused many local Republicans to stress a rhetoric of free enterprise and individual initiative. Vigorous champions of the American war effort after Pearl Harbor, the Republicans included a strong patriotic emphasis in their appeals. After 1945 returning veterans were welcomed, and often recruited as candidates, while veterans’ groups such as the were a significant entry path to political participation.

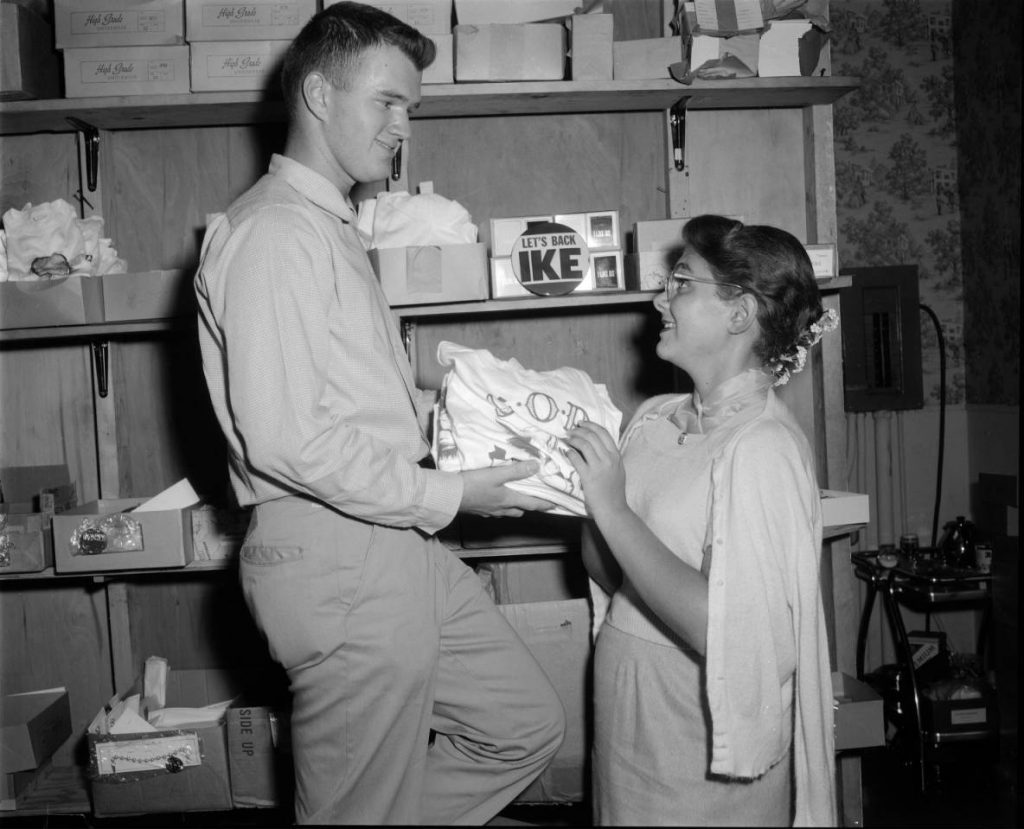

Many of these considerations came together in the 1952 election. The bulk of the GOP organization favored the presidential candidacy of a conservative midwesterner, Ohio Senator Robert Taft. But many voters, and one key party official, , supported the successful candidacy of Dwight Eisenhower. Although unsuccessful in supplying much local support for Eisenhower at the Republican National Convention, Brown won favor for his efforts—and was a major voice in national patronage and funding for the next eight years. From his public offices, notably as county clerk, and from his party post as national committeeman, Brown became the key power broker in the party. He was able to control the selection of county chairmen, institute a candidate screening process that assisted the nomination of his local candidates, and form alliances with two succeeding Republican governors, George Craig and Harold Handley.

Brown’s interests often touched upon state and national concerns, and his critics quickly pointed out that he was less successful locally. For example, he was never elected a GOP mayor for the old city of Indianapolis. But Brown’s influence did not decline seriously until his party lost the White House in the 1960 election. Brown held power for a few more years, serving his only terms as county chairman from 1962 to 1966. But his flirtation with the Nelson Rockefeller campaign of 1964 before Barry Goldwater’s nomination, and a subsequent poor organizational showing in support of Goldwater, combined to attract new allies to Brown’s long-standing party opponents. In 1964 these critics formed a Republican Victory Committee to oppose him, and two years later that committee was substantially broadened to become the Republican Action Committee (RAC).

The RAC set in motion a reorganization of the Marion County GOP that shaped the party until the 1990s. , Charles Applegate, , and W. W. Hill, successfully led the RAC and carried a slate of primary candidates in opposition to Brown. They then elected Bulen as county chairman. Victory in the November 1966, county election was followed by the nomination and election of as mayor in 1967. Lugar’s election set the stage for a sweep of the county’s legislative delegation in 1968 and the ensuing passage of the 1969 Unigov law. By combining the old city and the remainder of the county for the election of the mayor and council, enabled the GOP to draw upon its growing suburban base in future elections.

Many of these successes were institutionalized during the lengthy party chairmanship of . An engineer by training, and a former city director of public works, Sweezy succeeded Bulen as party chairman in 1972, winning the first of ten unopposed elections to that position. A skilled planner and manager, Sweezy redirected the party with an emphasis on volunteer participation, extensive fundraising, and recruitment. Sweezy compiled a series of election successes, especially for local government’s less visible offices. He also played an active role in recruiting ticket-leading candidates with strong media appeal, such as the two mayors who succeeded Lugar: and . Yet the emphasis on candidates and media in campaigns served as a reminder that there was always more to local politics than just organizational efforts. By the 1990s new national issues, a new generation of voters, and growing reliance upon the media all suggested that another party reorganization was likely.

*Note: This entry is from the original print edition of the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (1994). We seek an individual with knowledge of this topic to update this entry.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.