In the 1850s, when several new rail lines converged on Indiana’s fledgling state capital, a popular view emerged that Indianapolis was the “Railroad City.” The sheer number of railroads penetrating the helped prompt this moniker, as did the fact that tracks crowded in on the little town from several directions.

The original (1853) located just south of the Circle became almost instantaneously the hub of a large “transportational wheel” whose spokes projected outward to many points of the compass. Other developing urban centers from the Atlantic coast westward were also becoming focal points for rail lines, some of them—Chicago, for example—outstripping Indianapolis in the number of lines serving them.

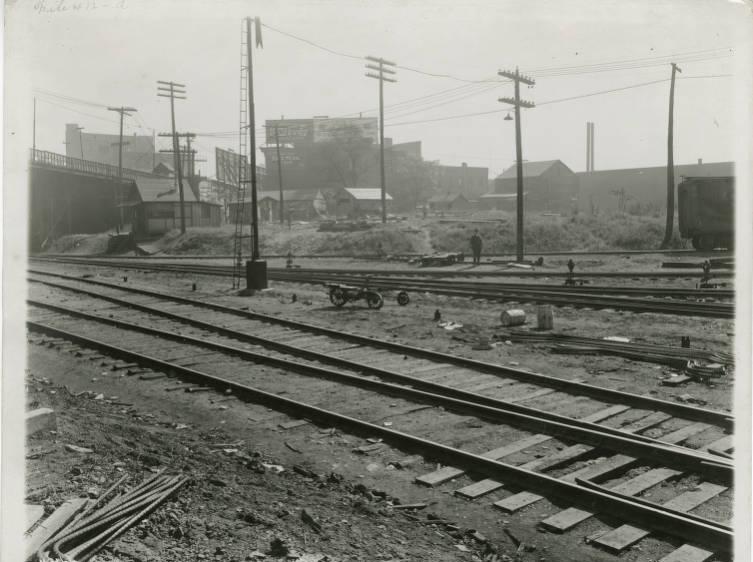

Nevertheless, Indianapolis over succeeding decades remained a conspicuous example of this mode of transportation and deserved its appellation. The numerous rail lines not only helped bring commercial and industrial prosperity but also played a prime role in determining the geographic patterns of the developing city by establishing extensive corridors from Union Station outward where businesses could locate. Positive and negative aspects of this spatial process represent the legacy of these early railroads.

1830s-1870s

The years from 1830 to 1870 marked the pioneer period of Indianapolis’ railroad development. Of the eight initial railroad charters issued by the State of Indiana (1832), five of them directly involved Indianapolis. Only two rail lines were built under these earliest charters: the Lawrenceburg & Indianapolis and the Madison, Indianapolis & Lafayette. They were to receive financial help from the state under the Mammoth Internal Improvements Act of 1836. An abbreviated version of the latter line (renamed the , or M&I) became Indiana’s first operable steam railroad (1847).

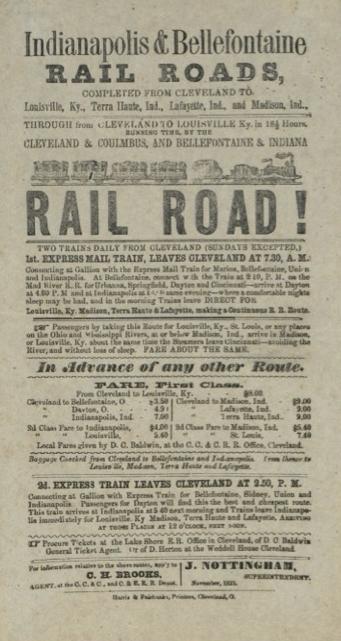

As a reaction to the initial success of the M&I and the state’s liberalized charter policy under the 1851 Constitution, construction began on several other projected lines. By 1855, 7 of the 16 lines that would ultimately serve the city were in place: the Bellefontaine (to Union City); the Terre Haute & Richmond (to Terre Haute); the Jeffersonville (to Jeffersonville via the M&I tracks down to Columbus); the Peru & Indianapolis (to Noblesville); the Lafayette & Indianapolis; the Lawrenceburg & Upper Mississippi (to Lawrenceburg with connections to Cincinnati); and the Indiana Central (to the Ohio state line via Richmond). Twelve years later 2 additional lines opened: the Indianapolis & Vincennes; and the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Indianapolis (a second line to Cincinnati).

This early group of railroads performed multiple functions their later counterparts would adopt and expand. They served as a convenient and inexpensive method for moving large amounts of commodities such as grain and coal into and out of Indianapolis’ developing hinterland. They also provided Indianapolis with transportation connections to distant regions— the Atlantic seaboard, the trans-Mississippi West via St. Louis, and the American South via Louisville and Cincinnati. Commodities brought into the city over these pioneer lines for local consumption, processing, or transshipment typically were surplus Hoosier farm and forest products, along with growing quantities of industrial products identified during the early years simply as merchandise.

Most Indianapolis rail lines during the Civil War were at least marginally prosperous while helping the city serve as an important logistics center for Union armies in the western campaigns. After some initial managerial confusion, the railroads proceeded to do on a larger scale what they had grown accustomed to doing over the preceding decade: haul various kinds of freight and transport people. Their crucial contribution to the war effort paved the way for the expansion of peacetime services, but problems and organizational changes quickly followed and continued almost to the end of the century.

1870s-1900

A basic postwar issue, reminiscent of the mid-1850s, was the competition among Indiana’s rail lines, including those terminating in Indianapolis. A standard solution was to gain an advantage over the competition by improving services. Since such effort led to increased developmental and operational costs, the railroad companies most firmly rooted financially had a clear advantage. Generally, this meant the large railroad systems with established headquarters in eastern cities. Major eastern rail corporations—among them the , the , and the —extended their influence to the Midwestern states and the city of Indianapolis.

Preceding the assimilation of the Indianapolis rail lines into these large systems, most of the lines experienced bankruptcy or operation under receivership. The corporate relationship between the individual rail lines and the systems varied, but localized lines generally lost their earlier identities and became linked popularly as well as officially with their new corporate parents. Indianapolis lines eventually absorbed into the Pennsylvania Railroad system were the Jeffersonville (the Jeffersonville, Madison and Indianapolis), the Indianapolis & Vincennes, the Terre Haute & Richmond, and the Indiana Central.

The lines coming under the control of the Big Four components of the New York Central system were the Indianapolis & Bellefontaine, the Lafayette & Indianapolis, the Lawrenceburg & Upper Mississippi, the Indianapolis & St. Louis, and both the eastern and western sections of the Indianapolis, Bloomington & Western. The Baltimore & Ohio established an east-west line through Indianapolis by taking over what had been the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Indianapolis and combining it with the Indianapolis, Bloomington & Springfield.

Meanwhile, other consolidations designed to enhance Indianapolis’ rail connections took place. What had once been the Peru & Indianapolis was absorbed by the Lake Erie & Western. The Louisville, New Albany & Chicago Railroad (), an in-state rail system, assumed control of the partially narrow-gauged Chicago & Indianapolis Airline, thus establishing an additional link between Indianapolis and the Chicago region.

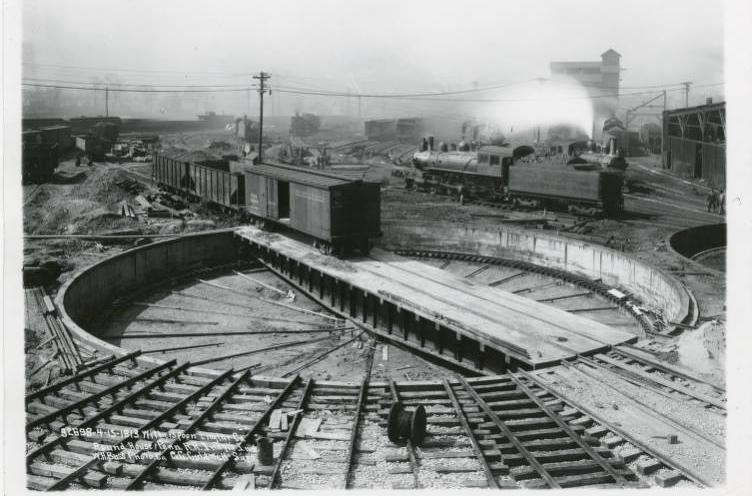

Because of its involvement with railroads and its developing industrial establishment, Indianapolis experienced serious economic troubles in the 1870s. One notable episode of the decade was Mayor John Caven’s effort during the nationwide to end a hunger crisis in the city by putting jobless men to work resuming construction of the . Circuiting a major part of the youthful city, the Belt eventually connected with all of the city’s railroads, enabling easy interchange of traffic and avoiding the congestion around Union Station. The enhanced flow of rail traffic added to the commercial and industrial potential of areas of the city dependent on rail transportation.

Along with the further development of its rail facilities during the post-Civil War decades, the city showed impressive population, territorial, and economic gains. By 1900, its population had risen to 169,164, and its boundaries extended as far as six miles from the Circle. New manufacturing facilities, particularly foundries, machine shops, and other metalworking establishments, created an industrial base in the growing city. By the close of the 19th century, the huge stockyards and meatpacking facilities on the White River, served by four rail lines plus the Belt, were processing over a million hogs annually—almost triple the number identified with the city of Cincinnati when it had the coveted nickname of “Porkopolis.”

1900-1920

By 1900, the total assessed value of property in Marion County had grown to over $138 million, about 3 percent of which represented railroad company properties. The latter included locomotives, cars, rights-of-way, classification yards, several small depots and freight houses, the new Union Station (1888), and several repair shops. The New York Central installation at Beech Grove in the southeastern part of the county was destined to become the largest and most comprehensive railroad repair facility in Indianapolis (see ).

For the eastern half of the United States, the state of Indiana, and the city of Indianapolis, the first two decades of the 20th century marked a high plateau of railroad service and achievement. Two lines were added to the Indianapolis rail network after 1900—chiefly for the hauling of coal mined in the southwestern part of the state. (These were the Illinois Central to Effingham, Illinois, 1903, and the Pennsylvania line linking Indianapolis and Frankfort, 1914.)

Most of the earlier lines improved and enlarged their facilities, greatly increased the frequency of freight and passenger runs, and continued to pursue technological advances that led to further convenience and safety. Although by 1920 the enormous steel mills of Indiana’s Calumet region had enabled Lake County to surpass Marion County in manufacturing, development of Indianapolis manufacturing continued on a dramatic scale. As in earlier years, industrial plants old and new relied heavily on their proximity to railroad service, with the city’s Belt Railroad continuing to play a prime role in this total transportation complex.

During the 1900-1920 period, the manufacture of automobiles and auto parts emerged as a major industry, with Indianapolis a leading center. Likewise, the building of railroad cars became a major Indianapolis enterprise by 1920, surpassing the still growing meat industry. Industries relating to food, clothing, and furniture reached significant levels in the city during the 1900-1910 decade.

World War I prompted an array of transportation problems not unlike those of the Civil War over a half-century earlier. Again Indianapolis railroads helped provide the transport services required to support mobilization. Due to massive delays in the shipment of war materiel to Europe, President Woodrow Wilson nationalized the nation’s railroads in December 1917 to take over their operation. Problems continued, but overall the situation improved. However, by the time of the withdrawal of this wartime jurisdiction (March 1920), the country’s passenger business had dropped 14 percent and its freight business 23 percent.

1920-1950

Generally, the country recovered from the post-World War I depression rather quickly, but railroads had a difficult time returning to normal. A major reason was the formidable competition resulting from the expanding use of automotive transportation—trucks, buses, and family cars. Indianapolis inevitably shared in this rail service decline. Indiana’s elaborate electric system, centered in the capital city during the 1920s, also contributed to the diminishing volume of passengers at Union Station.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, railroads serving Indianapolis continued operating despite the hard times that threatened bankruptcy and abandonment of routes and services. Preparation for war in the late 1930s placed a priority on use of rail resources throughout the country. America’s formal entry into World War II accelerated this demand as the nation’s railroads for the third time in a century provided much of the transport infrastructure for the military effort. Hustle and bustle at Union Station reached unprecedented levels, and the city’s total rail establishment came to life with renewed vigor and dedication. Following the war, Indianapolis’ rail lines once again returned to a precarious condition fostered by renewed transportation rivalry.

Like other American urban centers, Indianapolis in the decades after World War II continued to undergo the transportation revolution that had been well advanced during the prewar years. Other factors were involved, but it was the extensive use of family autos and large semi-trailers that was most responsible for these changes. Indianapolis assimilated these transport alternatives and, simultaneously, phased out what had become viewed as obsolescent. What to retain and what to eliminate became a crucial question.

1950s-Present

Initially, federal and state governments of the post-World War II years sought to curb the increasing number of rail abandonments by financially strapped companies. Following precedents established years earlier by some railroads, government policy encouraged giant consolidations such as Penn Central (1968) and later Conrail (1976), the former an abject failure and the latter a huge success. and CSX too resulted from combinations of many predecessor railroads.

Meanwhile a series of periodically updated “Indiana State Rail Plans,” prepared under the auspices of the state’s Division of Railroads, called for the subsidized preservation of portions of the surviving rail system on the basis of economic feasibility and the transportation needs of specific regions and communities of the state.

In keeping with this general policy, Indianapolis has retained its relative importance as a rail center, but there are several differences in what is shipped into and out of the capital as well as in the volume of transport business in terms of carloads. Since heavy industry does not predominate in the city, raw materials used in much of its manufacturing are relatively light and hence transportable by truck. This applies also to many of the city’s finished products. Only a small portion of coal and farm products, the state’s two largest commodity shipments, are directed toward Indianapolis. Thus the city’s previous role as a central clearing point for the distribution of goods by rail in several directions has been significantly altered.

Even so, despite cutbacks, changes in the quantity and variety of commodities entering and exiting the city, and the acceleration of transport competition—including that from airlines—Indianapolis has retained many of the features that a century ago prompted the title “Railroad City.” Most of the historic rail lines serving Indianapolis remain active and are operated by CSX and Norfolk Southern. In addition, some of the innovative Belt Railroad, operated by CSX, still circles much of the city core. These freight carriers, along with Amtrak’s passenger service, continue to position Indianapolis as a vital station on Indiana’s much-revised rail network.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.