Interurbans developed in the late 19th century as a result of technological breakthroughs in small electric motors and long-distance electrical transmission systems. Frank J. Sprague, a naval engineer from the East, played a major role in developing the new technology for streetcar systems within cities (Richmond, Virginia, and Chicago had early electric streetcars) and then for intercity systems. Given the pent-up demand for cheap, efficient intercity travel, interurban systems spread rapidly throughout the nation. Indiana had one of the earliest and most extensive systems in the country by which the capital city was connected with every other part of the state (except for Evansville in the southwestern “pocket”) long before World War I.

Indianapolis’ first interurban was the Indianapolis, Greenwood and Franklin Railroad. This line’s inaugural trip from Greenwood arrived in downtown Indianapolis at 11:30 A.M. on January 1, 1900. The first trip was a trial run; more linework was needed in Indianapolis before regular service could begin. Regular service to Greenwood began January 16 on an hourly schedule. The line was a success, carrying 330,000 passengers during its first year of operation. The one-way fare was 20 cents; round trips cost 30 cents.

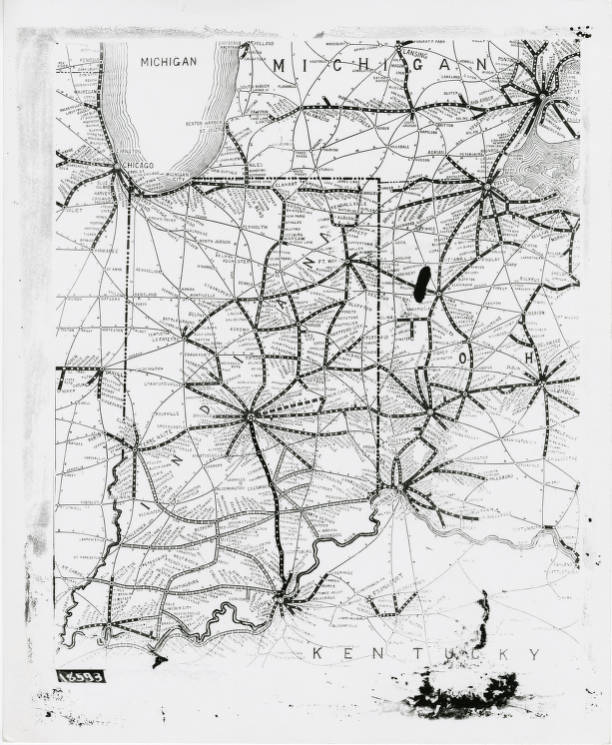

A second line also entered the city in 1900; the Indianapolis and Greenfield Rapid Transit Company began service from Greenfield on June 19. By 1910, when the last interurban line was completed into the city 12 separate companies operated direct routes to all major cities within 120 miles of Indianapolis, and, by connection, to all others within 200 miles.

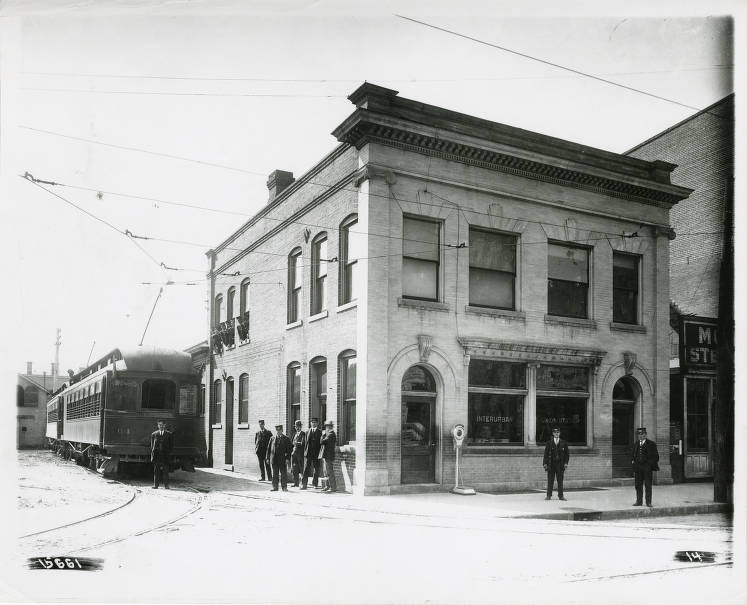

With the local interurban operations constantly increasing during the early 1900s, Indianapolis street traffic faced major congestion. To combat this problem, the companies entering the city began planning a terminal station for off-street passenger handling. The new complex was completed in 1904 and opened on September 12, the first day of State Fair week. During its first week, the handled an average of 10,000 passengers a day with a maximum of 25,000. In 1906, the first year for which complete figures are available, the terminal handled 4,469,982 passengers on 87,730 round trips.

During the next 10 years traffic in the terminal, the world’s largest interurban station, grew steadily, with a reported 7,208,747 passengers in 1916, carried on 694 cars in 462 trains per day. As the passenger traffic increased so did the number and length of the various intercity runs. By 1910, long-distance runs included Indianapolis to Fort Wayne via Muncie, 123 miles, or via Peru, 136 miles; Indianapolis to Louisville, 117 miles; and Indianapolis to South Bend via Peru, 170 miles. An even longer run, covering the 248 miles from Indianapolis to Zanesville, Ohio, began in 1916. This tiring nine-hour trip, however, could not compete with the faster steam railroad service between the two cities, and the run was soon dropped.

During their heyday, interurban lines greatly affected Indiana travel habits in general and the habits of Indianapolis residents in particular. Before electric lines, steam offered intercity transportation of people and goods throughout the state. This service, however, often operated only two or three times a day, usually to major cities and then not always at convenient hours.

The interurbans, on the other hand, ran frequent service—10 to 12 trains per day between the major cities—and at hours desired by the traveling public, usually between 6 A.M. and 11 P.M. or midnight.

Except for the “limiteds,” interurbans made all stops en route, including the country road crossings, and from the late 1920s most trains made all stops. Road names such as Stop 10 and Stop 11 in southern Marion County are present-day reminders of this bygone form of transportation.

The traveling public liked the comfortable, quiet, and clean ride and the cheaper fares. With lower ticket prices, the Indianapolis-Franklin line by 1902 had captured 98 percent of the local traffic from the Pennsylvania Railroad. The steam railroads retaliated with excursion bargains to points as far away as Niagara Falls. Ironically, many excursions were joint fares with competing interurbans.

Originally, Indianapolis merchants objected to the “noisy, dirty freight cars” on the city streets. But objections ceased with the beginnings of small package dispatch freight, an interurban service that allowed businessmen to ship orders quickly and economically to customers along the various lines. This service often allowed one-day order and delivery, an obvious selling point. Although this hurt smaller town merchants initially, soon they began using same-day delivery to compete with big city stores.

Larger orders required cars devoted exclusively to package freight, and these cars soon were hauled in scheduled freight trains. Other industries followed the trend, and carload shipments of logs, syrup, paper goods, auto parts, and livestock became common on most roads. The interchange of freight cars with steam railroads, however, was the exception rather than the norm because of differences in car equipment and objections from steam railroads.

As Indiana’s largest city, Indianapolis quickly became the center of this frenzied activity, and the large passenger and freight terminals were built to accommodate ever-increasing traffic demands. Indiana companies also were among the industry’s innovative leaders, offering pioneer train order dispatching, varied passenger equipment including parlor-diners and sleepers (one of only three sleeper operations in the country), special cars (express, railway post office), and the world’s largest traction terminal station in Indianapolis.

The 1920s started promisingly for the Indiana interurbans. The companies provided the traveling public more comfortable and safer equipment, including all-steel limited cars, parlor-diners, and sleepers. Roadbeds were improved for faster and smoother riding, and freight services were expanded with the addition of heavy locomotives, fast express service, and specialized freight cars. But other factors worked against the continued success of interurbans. The private automobile and the paved highway system caused a decline in interurban passenger traffic: almost 40 percent by the end of the 1920s. Several smaller lines either went out of business or merged into larger and stronger companies.

All the companies serving Indianapolis, however, survived the decade in fairly strong financial positions until the stock market crash of 1929. The resulting widespread financial failures severely affected the interurbans and their parent, the electric power industry. Many companies abandoned operations, although some managed to keep operating for a few more years, hoping vainly for a revival that never occurred.

Early in 1930, two large companies serving Indianapolis, Union Traction and Interstate Public Service (successor to the original Indianapolis, Greenwood and Franklin), combined forces to combat their developing financial problems. On August 1, 1930, the new company, Indiana Railroad (IR), began the operation of all the properties. It quickly disposed of over a hundred miles of unprofitable lines (none serving Indianapolis) and dropped the parlor-dining service between Indianapolis and Louisville.

The other two companies serving the city, Terre Haute, Indianapolis and Eastern Traction Company (THI&E) (which had merged several of the smaller companies in west-central Indiana) and Indianapolis and Southeastern Railroad, successor to Indianapolis and Cincinnati Traction, continued to operate independently. But Terre Haute, Indianapolis, and Eastern abandoned most of its Indianapolis service on October 31, 1930, dropping routes to Martinsville, Danville, Crawfordsville, and Lafayette.

Eight months later Indiana Railroad took over the THI&E line from Indianapolis to Terre Haute, plus other tracks in the Terre Haute area. These acquisitions gave IR total interurban trackage of 850 miles, by far the largest of any company in the entire United States. The company also operated another 100 miles of city lines. Still, the losses continued; 1932 brought abandonment of the IR’s Indianapolis-Dunreith line (forcing rerouting of the Indianapolis-Dayton service via New Castle and Dunreith), the Indianapolis and Southeastern lines from Indianapolis to Greensburg and Connersville, and the cessation of sleeper service between Indianapolis and Louisville.

The final blow to the interurbans was the passage in 1935 of the Public Utility Holding Act, which required holding companies to restrict their operations to a single integrated system and to “reasonably incidental or economically necessary activities.” This provision required the separation of power and railway operations, effectively leaving the railways without access to utilities’ resources. Although delayed in court for several years, the act was eventually upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court and the utilities began cutting back their railway operations.

In 1937, the suburban Beech Grove line failed, after many years of struggling with declining revenues and harassment by creditors. The , frustrated by continuing nonpayment of its bills, simply cut the power one morning and the line was no more.

Floods on the Ohio River and its many tributaries in January 1937 caused several breaks in service on the Indianapolis-Louisville line. In May, IR abandoned its Indianapolis-Dayton service. Ironically, just as the company was beginning to show a profit it suffered a long and difficult strike. By the time the strike was resolved, the company had lost all it had gained over its short but active life.

Other abandonments continued the downward trend: 1938, Indianapolis-Fort Wayne via Peru; 1939, Seymour to Louisville (leaving only the short Indianapolis-Seymour stub of the once prosperous Indianapolis-Louisville route); 1940, Indianapolis-Terre Haute; and 1941, Indianapolis-Fort Wayne via Muncie, and the final segment, Indianapolis-Seymour (following a fatal accident that wrecked two of the last four cars still in service).

Thus went the interurban in Indiana. From its tiny beginnings, the industry had grown to an extensive system connecting most of the major cities and villages in the state. Through the years, 111 different interurban companies operated more than 3,000 cars over the state’s 2,100 miles of line (a mileage figure second only to that of Ohio, a much more populous state).

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.