The earliest retail businesses in Indianapolis were general stores, farmers’ markets, and workshops. Currency was not widely available in the city until the branch opened in 1834, so customers bartered homegrown crops and hand-produced products for manufactured goods like nails and calico. Farmers sold their products at a city market first held in June 1822—in the maple grove on the Governor’s Circle (see ). A more permanent market house was built in 1832 on the half square just north of the courthouse on East Market Street. Artisans such as tailors, milliners, and shoemakers also manufactured items in their workshops and sold or bartered them.

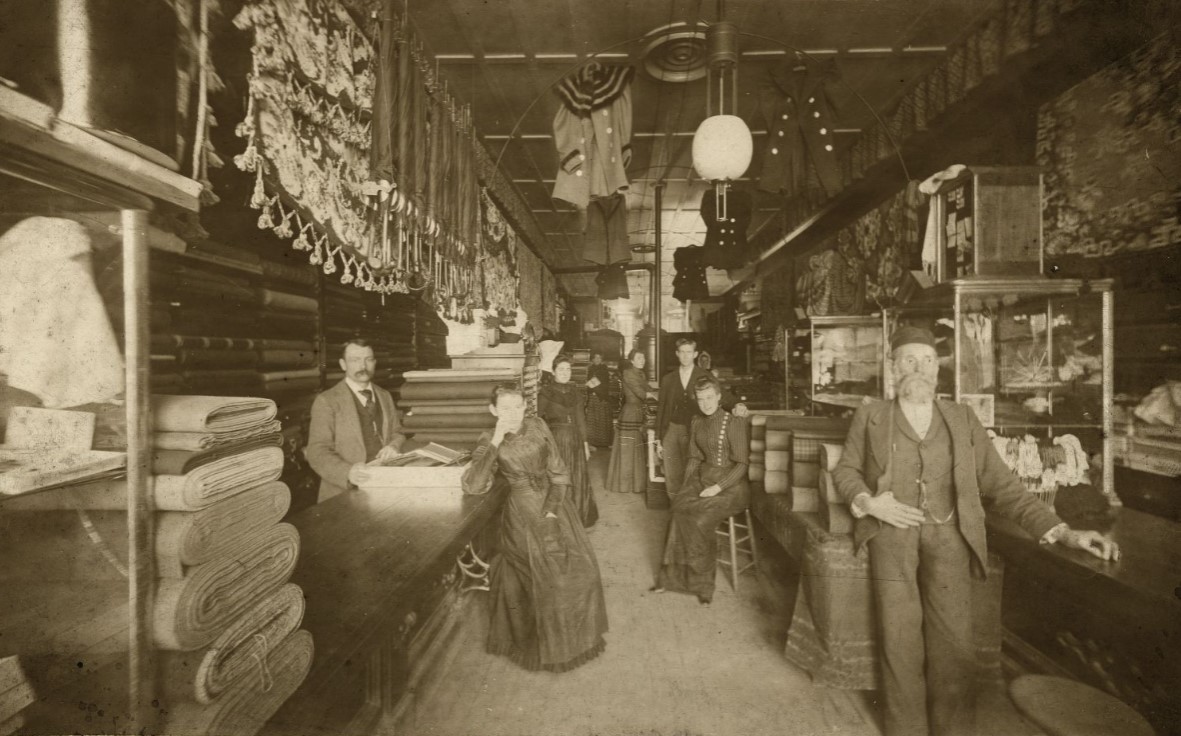

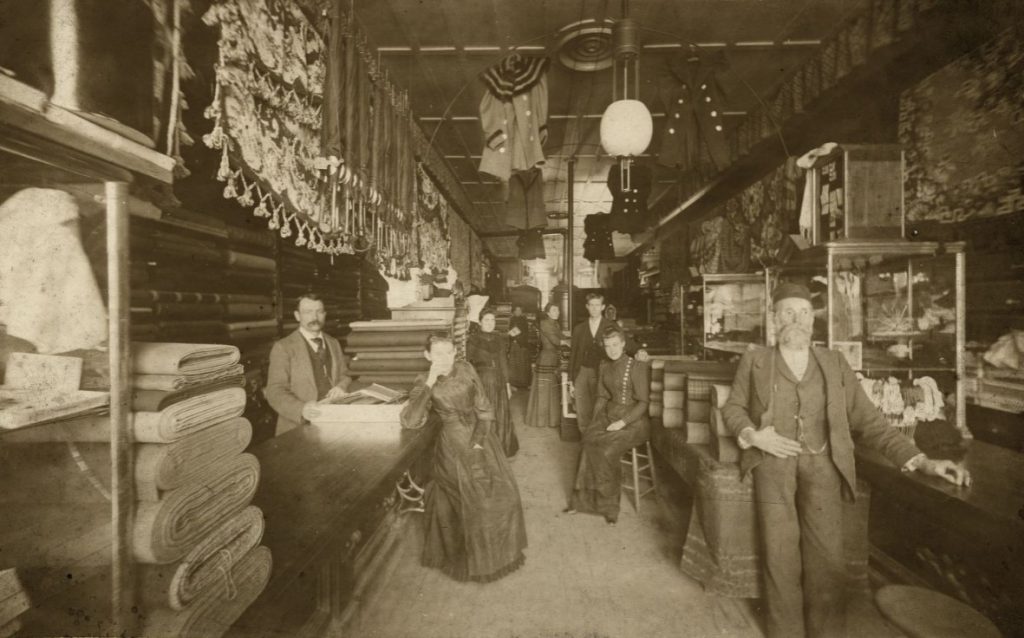

The new settlement’s first merchant, Daniel Shaffer, opened a little store on the high ground south of in the spring of 1821. He was followed by merchants who built stores in the platted area of the city, especially on Washington Street. A successful early merchant was , a German immigrant who opened a general store at 29 West Washington Street in November 1840. He sold goods such as candies, beer, groceries, “nerve and bon[e] lineament,” china, lumber, and toys. He bought local products from a brewer and an eggwoman and stored them in a rented cellar. He also ordered manufactured goods from Cincinnati and had them transported by Conestoga wagon up the rutted .

The first railroad to reach Indianapolis, the on October 1, 1847, changed the way local businessmen did business. On November 24, 1847, Charles Mayer advertised in the that shipment of freight was 50 percent less expensive using the railroad and that he could now sell a wider variety of goods at a lower cost. However, within a few years, the trend in retail businesses was to specialize and deal in a few lines of goods to lower expenses and prices.

The city’s 1857 business directory listed about 240 retailers. There were 60 grocery and produce dealers, 23 saloons, and 18 dry goods stores, as well as 2 agricultural stores, 5 bakeries, 8 booksellers and stationers, 16 boot and shoe dealers, 1 candle manufacturer, 2 carriage makers, 6 tobacco dealers, 3 coal dealers, 2 coopers, 6 confectioneries, 8 druggists, 4 gunsmiths, 1 ice dealer, l0 jewelers, 2 marble dealers, 1 silversmith, 1 straw goods dealer, and 1 wagon manufacturer. Nine women were listed as milliners and dressmakers, and for many years these were the only retail businesses in which women were listed.

During the , the transient population of Federal troops and their dependents temporarily boosted retail business. Illinois Street became lined with small retailers such as restaurants, clothing stores, jewelry stands, saloons, and grocery stores. New businesses began to locate on cross streets away from Washington Street as the city spread out. There was a rise in wages, but the depreciation in the value of currency and the inflationary increase of prices put a damper on the city’s business. The retail grocers agreed not to accept credit for goods, there were fewer manufactured goods available to customers, and most residents had to live frugally. In 1865 there were still only about 250 retail businesses listed in Indianapolis directories.

The growth of the city accelerated after the Civil War and the number and variety of retail stores grew with it. The gradual introduction of gas, electricity, telephones, a street railway, and road pavement, as well as the provision of a water supply and sewerage to the business district, helped the proliferation of new businesses. There were about 1,280 retailers listed in 1873, 2,090 in 1883, 3,390 in 1894, and 4,250 in 1904. The types of stores ranged from small specialized businesses, such as Frederick W. Simon’s neighborhood grocery store at 188 North Noble Street, Craig’s Confectionery Store at 6 East Washington Street, or Allison’s Perfection Fountain Pen Store at 157 North Illinois Street, to Pettis’ “New York Store” at 25-35 East Washington Street, which sold a wide variety of dry goods.

Some of the city’s famous retail firms began or expanded during the post-Civil War era. began selling hardware in 1851 and continued his business at 120-124 East Washington Street. Solomon Strauss began selling clothing in 1853 and emerged as a leading seller of men’s clothing. In 1872 bought controlling interest in the Trade Palace, a dry goods store at 26-28 West Washington Street, and assumed management two years later. In 1880 Bertermann Brothers Florist Shop was located at 74 East Washington Street. Julius A. Haag ran a drugstore at 87 North Pennsylvania Street in the new , and by 1889 the Haag family had one of the city’s first multiple listings with three stores. In 1889 Black businessman Henry L. Sanders opened his Gent’s Furnishings store at 15 ½ Indiana Avenue and developed a successful uniform-making business that continued for over 50 years. By 1894 was selling dry goods at 12-18 West Washington Street, and Polk’s Creamery was in operation at 325 East Seventh Street. In 1904 was listed at 318 Massachusetts Avenue.

At the beginning of the 20th century, retailers did not open on Sundays, the highest volume sales day was Saturday, and the highest volume month was December. The new provided customers with transportation to and from the downtown area and the retail stores of the new neighborhoods and suburbs of the expanding city. Some retailers took advantage of the new automobile manufacturing business in Indianapolis. National Motor Vehicles, for example, sold electric and gasoline autos at East 22nd Street and the Monon Railroad tracks. By 1904 ten stores were selling electrical supplies and one sold telephone apparatus. There were also 125 restaurants, 590 saloons, 750 grocery stores, several fruit stands run by Italian families in the East Market House, and John A. Hook’s drugstore at 1101 South East Street.

One retailing family successfully made the transition from the “horse-and-buggy” days to the automobile age by changing its line of business. A Scottish immigrant named Peter F. Bryce opened Bryce’s Steam Bakery at 14-16 East South Street about 1873, which specialized in “homemade” bread and butter crackers. In the 1920s his son, Robert M. Bryce, razed the old bakery and surrounding buildings and opened his automobile filling station on the block, which he operated successfully for many years.

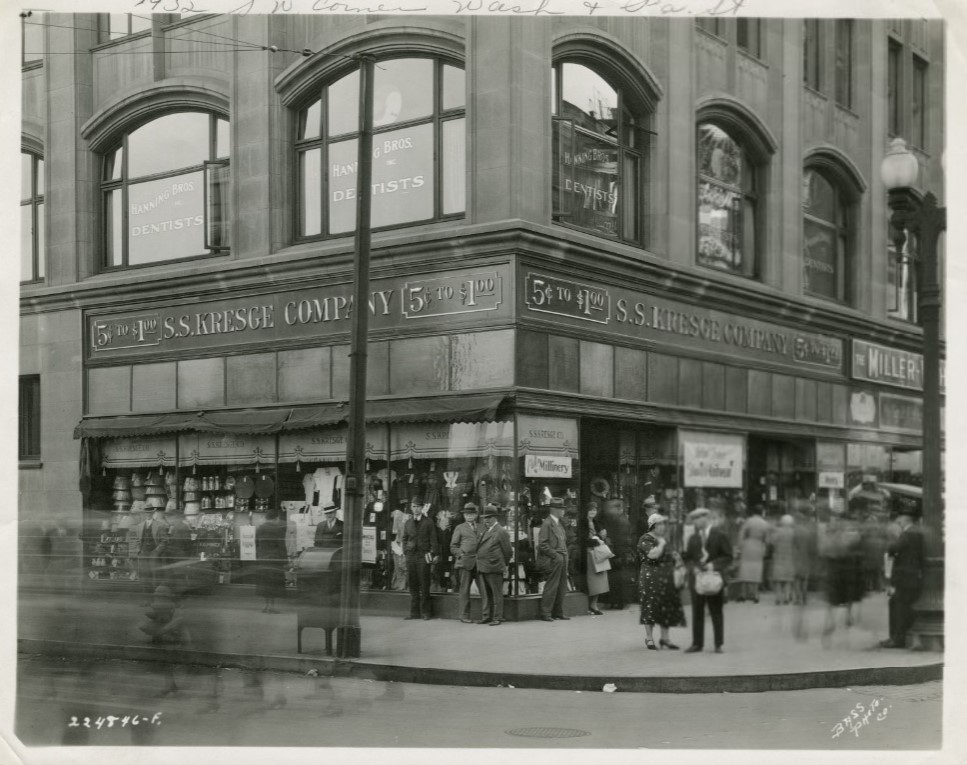

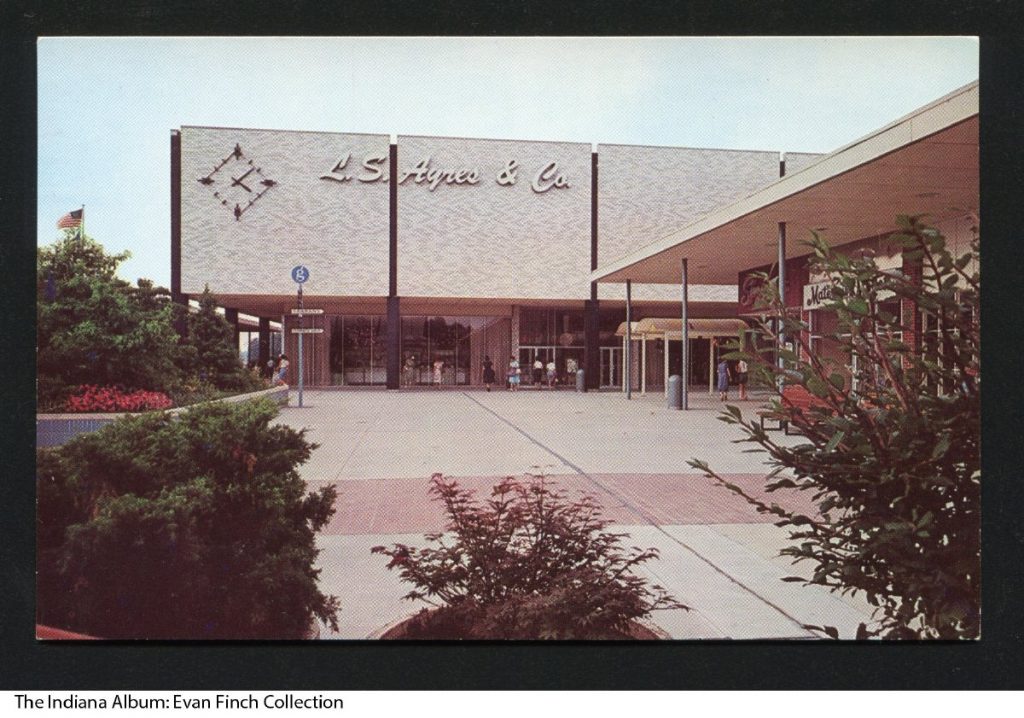

There were two separate national trends in retailing at the beginning of the 20th century. The first trend involved selling an increasingly diverse variety of goods in one store. Many dry goods stores, such as Pettis’, which generally sold material to make women’s clothing, began to employ dressmakers and milliners, as well as to sell shoes, carpets, and furniture. This was the first stage in the development of the department store. opened Indianapolis’ first modern department store on October 2, 1905, at 1 West Washington Street. Ayres eventually sold everything from books and flowers to men’s and women’s clothing and china to baked goods and candies. The store also provided a cafeteria and an elegant Tea Room. Other downtown retailers, such as at 26 North Illinois Street, also developed into department stores, but another form of the trend was the “five-and-dime” store that sold all of its goods at a low price. Turpin and Mathews was Indianapolis’ first “five-and-dime,” listed in 1893, and in 1906 the national chain S. S. Kresge opened a store at 23 West Washington Street.

The second trend in retailing at this time was the abundance of small, family-owned, neighborhood stores. These businesses were easy to start, required little formal training and long hours of work, and provided a living for many families. In 1914 there were about 4,200 retailers listed in Indianapolis, and about 1,000 of these were neighborhood grocery stores.

Automobile retailers were the fastest-growing type of modem businessmen in the first two decades of the 20th century. There were electric and gasoline automobile manufacturers who also sold autos and parts retail and automobile dealers who also ran recharging stations and filling stations, as well as used car dealers, auto accessory stores, tire stores, and gasoline filling stations. There was 1 auto retailer in Indianapolis in 1900, 8 in 1904, 55 in 1914, 99 in 1917, and in 1921 about 130 retailers sold autos and auto accessories, not including 20 filling stations. These retailers provided the city with the transportation to expand beyond its old limits.

In 1921, about 5,000 retailers had business listings in the city. Again the food selling business was the largest, with about 1,300 grocers, 570 meat markets, 370 restaurants, 130 confectioneries, and 180 soft drink sellers. Also, Standard Grocery stores had opened 31 units, the national Piggly-Wiggly chain had 12 grocery stores in the city, and and had five stores each. Though modern items such as phonographs, film, refrigerators, machinery, electrical supplies, and furnaces were sold widely there were still 46 blacksmiths, 11 harness and saddlery shops, and 3 horse and mule dealers listed.

The federal government first took the census of the retail trade in 1929, and it was taken about every five years thereafter. The census counted 4,920 retailers in Indianapolis in 1929. The most dramatic change in retailing since 1921 was the number of chain stores, which increased from about 70 total to 472 units of local chains, 176 units of sectional chains, and 396 units of national chains. These chains included not only grocery stores and drugstores, but also variety stores, shoe stores, and filling stations. The automobile group of retailers increased to 769, including 392 filling stations.

By 1933, the had hit Indianapolis hard. The number of retailers dropped to 4,494, the average annual net sales declined from $44,808 to $23,181, and the average number of employees per store declined from five to three. The hardest hit retailer was the small neighborhood grocery store, the number of which dropped to about 800. By 1939 the number of retailers rebounded to 5,208 with average annual net sales of $36,204. There was not a dramatic increase in any one type of retailer, and the population remained stable though residents continued to move away from the center of the city and neighborhood retailers were more predominant.

During World War II a retail census was not taken, but the 1948 retail census showed a sizable increase in retail sales with a general consolidation of business. In 1948 there were 4,650 retailers in Indianapolis with average annual net sales of $126,063. In 1954 there were 4,632 retailers in the city, but their average net sales increased to $166,344 and they employed an average of eight employees each. From 1929 to 1954 the number of grocery stores and other food-selling establishments dropped from 1,757 to 905, but the number of eating and drinking places increased from 584 to 933.

In the early post-World War II era, street corner drugstores such as Hook’s and Haag’s became anchors of a few connected retail outlets at the busiest intersections around the city’s neighborhoods. This led to the development of 17 shopping plazas throughout Indianapolis by 1961. Eastgate opened in 1957 at 7150 East Washington Street with 52 outlets, and Glendale in 1958 at 6101 North Keystone Avenue with 54 outlets. (See for more information.) The bigger plazas had at least one department store as an anchor for the other business outlets, which included grocery, drug, shoe, variety, hardware, and wearing apparel stores, eating and drinking places, and other specialized retailers.

The total number of retailers in Indianapolis varied between 1958 and 1987. By 1958 the city’s increase in population and business accounts for the 5,159 retailers in the city, but the general exodus of the middle class to the suburbs outside the city’s limits probably caused the number to drop to 3,905 in 1963. The expansion of the city’s boundaries by Unigov (see ) brought the 1972 count of retailers to 5,766. This number fell to 4,760 in 1987 because of the increase in the number of large-volume national chain stores that local small retailers could not compete against. The average annual net sales per store climbed steadily from $167,846 in 1958 to $348,835 in 1972, jumped to $610,945 in 1977, and doubled in 1987 to $1,384, 904. The average number of employees per store between 1958 and 1982 stayed between 8 and 11 but increased to 16 in 1987. By 1987 the retail census listed 196 building material and garden supply, 110 general merchandise, 435 food stores, 293 automotive dealers, 334 gasoline service stations, 492 apparel and accessory stores, 394 furniture and home furnishings stores, 1,373 eating and drinking places, 159 drugstores, and 1,017 miscellaneous retail stores within the Unigov boundaries of Indianapolis.

Developers continued to build ever-larger shopping centers around the periphery of Indianapolis in the 1960s and 1970s. Greenwood Shopping Center opened to the south of Indianapolis in May 1965, and Lafayette Square to the west in August 1968. After I-465 looped around the city by the early 1970s, Castleton Square opened to the north of the city in September 1972, and Washington Square to the east in October 1974. This combination of malls and plazas drained the downtown area of its retail business by 1976. After the huge bicentennial celebration in downtown Indianapolis, the city’s leaders conducted a well-planned campaign to revive the retail business downtown, especially in the restored . But the economic slump of the late 1980s affected all the city’s retailers. In January 1992, L. S. Ayres closed its original flagship store, which eventually left downtown Indianapolis without a department store for the first time since 1905.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, the city of Indianapolis and shopping mall developer Melvin Simon and Associates (see ) planned and built the located in the old retail district of downtown. Situated on three and one-half blocks bounded by Market, Meridian, Georgia, and Illinois streets, the Circle Centre Mall opened with great fanfare on September 8, 1995. The mall showcased about 180 retail shops, stores, and restaurants, including the historic, renovated L. S. Ayres building in about one million square feet of retail space.

*Note: This entry is from the original print edition of the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (1994). We are currently seeking an individual with knowledge of this topic to update this entry.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.