The automobile has changed every American city throughout the 20th century, those of middle size perhaps even more than the largest. Indianapolis felt the effects with full force, not only as its residents began to drive, but as increasing numbers of them worked to build automobiles and auto parts. From 1911 onward the city’s most popular public occasion was a spectacular 500-mile automobile race which attracted enormous crowds and was soon known nationwide as the “Indianapolis 500.” Unlike Detroit, however, Indianapolis did not develop mass automobile production, requiring giant factories and a large force of semiskilled labor.

The impact of the automobile was most clearly described by , the city’s foremost novelist, who saw as early as 1918 that his beloved Indianapolis was changing almost beyond recognition. No American writer described so clearly or so early the overwhelming impact of the automobile on the nation’s cities. In , Tarkington created a family which prospered greatly from real estate investments during the 1870s and then lost everything during the 1910s as the automobile devastated established property values and shifted development to the suburbs. In a famous scene, the young and foolish George Amberson Minafer attacks Eugene Morgan, an automobile inventor who is courting his widowed mother. “Automobiles are a useless nuisance,” says George. “They had no business to be invented”. George’s grandfather, the wealthy real estate investor, remarks that the growing number of automobiles would soon drive pedestrians and carriages from the streets. “We’ll even things up by making the streets five or ten times as long as they are now,” Eugene answers. “It isn’t the distance from the centre of town that counts, it’s the time it takes to get there. This town’s already spreading; bicycles and trolleys have been doing their share, but the automobile is going to carry city streets clear out to the county line”. In 1918 this seemed only a dream, but by the 1960s it was a reality on the north side of Indianapolis. As the old man feared, “real estate values in the old residence part of town are going to be stretched pretty thin.”

Tarkington was no admirer of the automobile age, and he never mentioned the “500” in any of his many stories about Indianapolis. Nevertheless Tarkington gave to Eugene, the inventor and manufacturer, a wise and cautious answer for the brash young man who claimed that automobiles ought never to have been invented. “I’m not sure he’s wrong about automobiles,” Eugene replies. “With all their speed forward they may be a step backward in civilization…But automobiles have come, and they bring a greater change in our life than most of us suspect. They are here, and almost all outward things are going to be different because of what they bring…I think men’s minds are going to be changed in subtle ways because of automobiles…Perhaps, ten or twenty years from now, if we can see the inward change in men by that time, I shouldn’t be able to defend the gasoline engine.”

Tarkington received the Pulitzer Prize for but few readers took seriously his doubts about the automobile age. Indianapolis was booming with new automobile factories, bringing more jobs for its workers, more traffic on its streets, a building boom in its suburbs, and, as Tarkington feared, making it a place where “the streets were thunderous” and “a vast energy heaved under the universal coating of dinginess” in the “smoky bigness of the heavy city.” For better or worse, Indianapolis was becoming an industrial center.

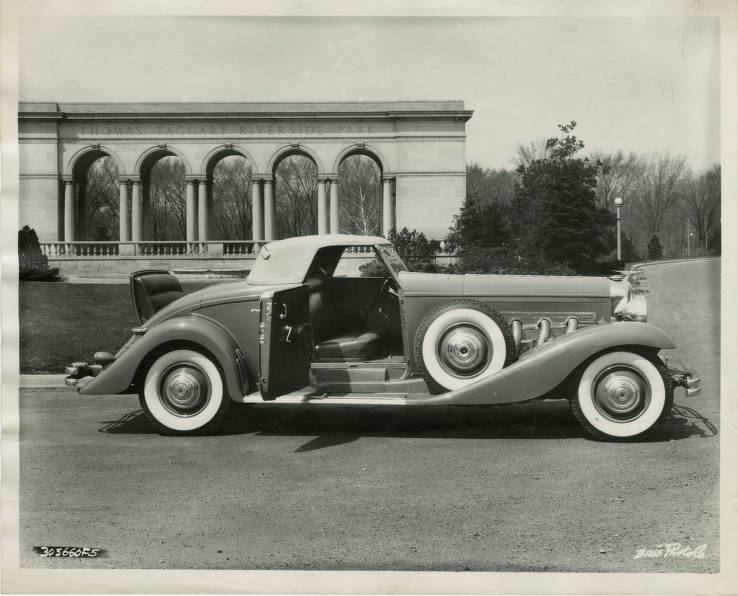

The boasted in 1921 that Indianapolis led the world in the manufacture of “better grade automobiles.” Whether true or not this claim to leadership in an important part of the automobile industry shows clearly how the city’s business leaders saw Indianapolis as the “Capital of the Land of Opportunity.” Unlike the centers of low-priced automobile production in Michigan, Indianapolis took pride in its “almost ideal” labor conditions and its high proportion of American-born residents. Immigrants and labor unions played almost no role in the business vision of Indianapolis.

The city’s population more than doubled between 1900 and 1930, the years of the automobile boom in Indianapolis, but the number of wage earners in manufacturing increased by only 87 percent. Automobile workers outnumbered those in any other industry by 1919, but their share of the work force declined significantly during the 1920s, even before the Great Crash in 1929. Limited production luxury cars such as , , and drew attention wherever they appeared, but only a few thousand workers were employed to manufacture them. Indianapolis was famous for its fast and elegant cars, but they remained a rare sight even on their hometown streets.

Automobiles replaced horses with remarkable speed on city streets; the animals had almost disappeared by 1919. Automobile dealers created a prosperous new business district about ten blocks north of downtown on Capitol and Meridian streets. The annual auto show at the each winter attracted large crowds to see the new models, and service stations occupied a growing number of corner lots. By the early 1920s the automobile had become an inescapable part of city life in Indianapolis, even though most city residents did not yet possess cars of their own. Drivers seized control of the streets and pedestrians learned from childhood to “Look before crossing the street.”

The automobile also brought noticeable changes to the city’s network of streets. Although the fundamental Indianapolis street plan of a rectilinear gridiron with four diagonal avenues was fixed from the city’s founding, developed a grand plan of improvements in 1908. Kessler, a landscape architect and city planner from St. Louis, worked as a consultant to the city park board for many years. He planned a comprehensive boulevard system along the city’s waterways and directed much of its construction (see ). Kessler began with Fall Creek Parkway, and explicitly argued that it would improve traffic flow, although his reports never directly mentioned automobiles. Within a few years Kessler reported significant residential construction along and near the new boulevards, although his long-range plan would require decades for completion. Both Fall Creek and would have boulevards along both banks, as would Pleasant Run on the southeast side, with major improvements for Garfield and Riverside (later Taggart) parks. On the northern edge of the city 38th Street would become a grand boulevard (alternatively called Maple Road and Parkway Boulevard), as would Capitol Avenue from downtown northward to Fall Creek. and played no significant role in the development of these boulevards; they were designed to accommodate automobile traffic.

Kessler returned to Indianapolis in the early 1920s to plan an outer boulevard system for the spreading city. He began on the north side with a broad street extending from westward to Big Eagle Creek and then southward, the route later known as Kessler Boulevard, but his ambitious plans were left unfinished after Kessler’s death in 1923. Meridian Street north of 38th Street, which became the city’s most elegant residential boulevard during the 1920s, was not part of Kessler’s plan. Meridian Street was emphatically a creation of the automobile era and was never served by trolley cars.

Except for the incomplete boulevard system, which grew out of the pre-automobile City Beautiful movement, Indianapolis and Marion County lacked any sort of comprehensive street and traffic planning. By the early 1920s traffic congestion was a serious problem downtown, slowing trolley and interurban cars which shared the streets with growing numbers of automobiles. Traffic and parking problems were frequently discussed but never solved. Electric traffic lights replaced police officers to control traffic at busy intersections in 1925, and the city introduced comprehensive downtown parking restrictions in 1931, supplemented by hated parking meters in 1939 and one-way streets in the early 1950s.

As a national highway system developed, Indianapolis became a vital crossroads. Local business leaders, particularly such auto men as and , played a leading role in the Good Roads Movement and were among the chief promoters of the Dixie Highway, extending from the Great Lakes to Florida. With the coming of the federal highway numbering system in 1925, Indianapolis was at the junction of two of the most heavily traveled cross-country routes—U.S. 40, which extended from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and U.S. 31, stretching from northern Michigan to the Gulf of Mexico—as well as three lesser federal routes.

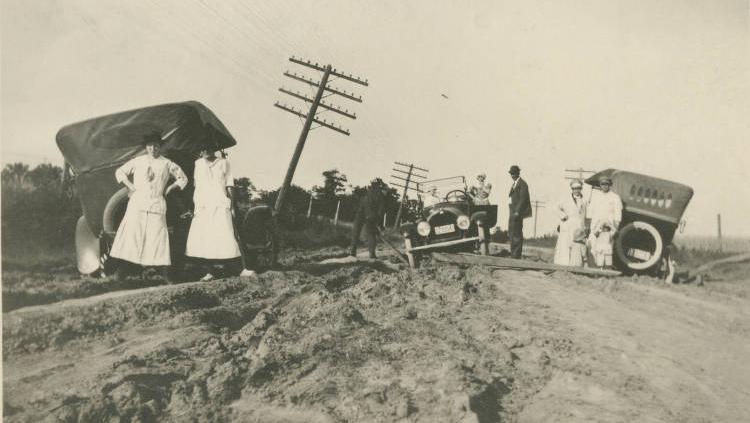

Within Marion County, however, there was no planning and little improvement in the rural highway system as the growing population spread far beyond the slowly expanding city limits. A 1916 map showed only two road surfaces, “Gravel or improved roads” and “Ordinary or mud roads.” By the early 1920s most of the traditional county section-line roads were paved with gravel, but no new roads were built. Not until 1942 was there an effort to expand the county road system with the construction of a belt-line box eventually known as State Road 100, extending north from U.S. 40 to on the east (Shadeland Avenue), and then westward to U.S. 52 along 82nd and 86th streets. The western and southern segments were never completed as suburban home builders worked more quickly than state and county highway officials.

Both city and county travel was revolutionized with the arrival of the interstate highway system in the late 1950s. More than ever before Indianapolis was the “Crossroads of America.” Two of the most important interstate highways, 1-65 and 1-70, met two lesser routes at Indianapolis, 1-74 and 1-69, all feeding traffic into an unnamed circumferential highway known only as I-465. The two major interstates penetrated the city and formed an Inner Loop around the downtown area which required the demolition of hundreds of homes and businesses and disrupted the existing street system. Proposed north and northeast freeways were never funded, saving many of the city’s more affluent neighborhoods from further devastation, while the Madison Avenue Expressway (opened 1958), extending southward from downtown, carried only limited traffic. Highway planners and downtown business interests of the 1960s imagined that the greatly improved highway system, not complete in Indianapolis until 1976, would make it easier for drivers to reach the traditional retail and office concentration downtown. By the mid-1970s, however, it was clear that people who lived in the suburbs and traveled only by automobile would reject downtown congestion for suburban shopping malls, which soon produced even greater congestion. By the 1980s suburban office complexes, many adjacent to I-465 interchanges north and northeast of the city, had largely replaced downtown office buildings. The nature of the city was changing beyond recognition as the automobile reigned supreme. Just as Tarkington had predicted a half century earlier, real estate values in older parts of town declined sharply. Rather than travel by trolley to the downtown stores, theaters, and restaurants, everyone who could afford an automobile drove to a suburban mall or shopping center, leaving downtown for daytime office workers, convention goers, sports fans, and those without the resources to afford a car.

The most visible influence of the automobile in Indianapolis occurs each May with the 500-Mile Race, long considered the “greatest spectacle in racing.” No American sporting event has enjoyed as many paying customers as the Indianapolis 500, which attracted crowds of 150,000 during the 1920s and triple that number by the 1990s. From 1919 this was the outstanding automobile race in the United States, and for many years it attracted European cars and drivers as well, just as its official name, the International Sweepstakes, suggested. For Indianapolis, the 500-Mile Race was the only sporting event of more than strictly local interest. The city was too small for major league baseball and its colleges were unknown among football fans. Daring race car drivers became heroic figures, and the danger of crippling injury or death on the track only added to their fame. The flamboyant Carl G. Fisher was the city’s most famous businessman, presiding annually at the “500,” the nation’s longest automobile race and the only competition at the Speedway. Traditionally, only the great occasion on Memorial Day mattered, for parades and festival events outside the Speedway began only in 1956.

By 1970, when Unigov combined the governments of Indianapolis and Marion County for many purposes, the automobile dominated local transportation, and an increasing share of public and private expenditure was devoted to roads, streets, and parking facilities. At last, however, all of Marion County had a single government department in charge of streets and roads, except for state-controlled highways. By then suburban expansion had extended beyond the county line and construction of new, wider roads meant enormous expense and determined opposition from affected property owners. Those who mattered socially and politically used their automobiles to travel everywhere they wished to go, and governments and businesses had little choice except to provide the facilities drivers demanded. Traffic congestion is the curse of the modern American city, and highway improvements only increase traffic even further. Indianapolis, like all American cities, is both dominated and devastated by the automobile. As Booth Tarkington warned in “The World Does Move,” a short story of 1928 in which he reminisced about the early days of the automobile, “The quiet of the world is ending forever.”

*Note: This entry is from the original print edition of the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (1994). We are currently seeking an individual with knowledge of this topic to update this entry.

FURTHER READING

- Whitaker, Sigur E. The Indianapolis Automobile Industry: A History, 1893-1939. McFarland and Company, Inc, 2018. https://search.worldcat.org/en/title/1028050782.

CITE THIS ENTRY

APA:

Furlong, P. J. (1994). Automobile Culture. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Retrieved Feb 17, 2026, from https://indyencyclopedia.org/automobile-culture/.

MLA:

Furlong, Patrick J. “Automobile Culture.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 1994, https://indyencyclopedia.org/automobile-culture/. Accessed 17 Feb 2026.

Chicago:

Furlong, Patrick J. “Automobile Culture.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 1994. Accessed Feb 17, 2026. https://indyencyclopedia.org/automobile-culture/.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.