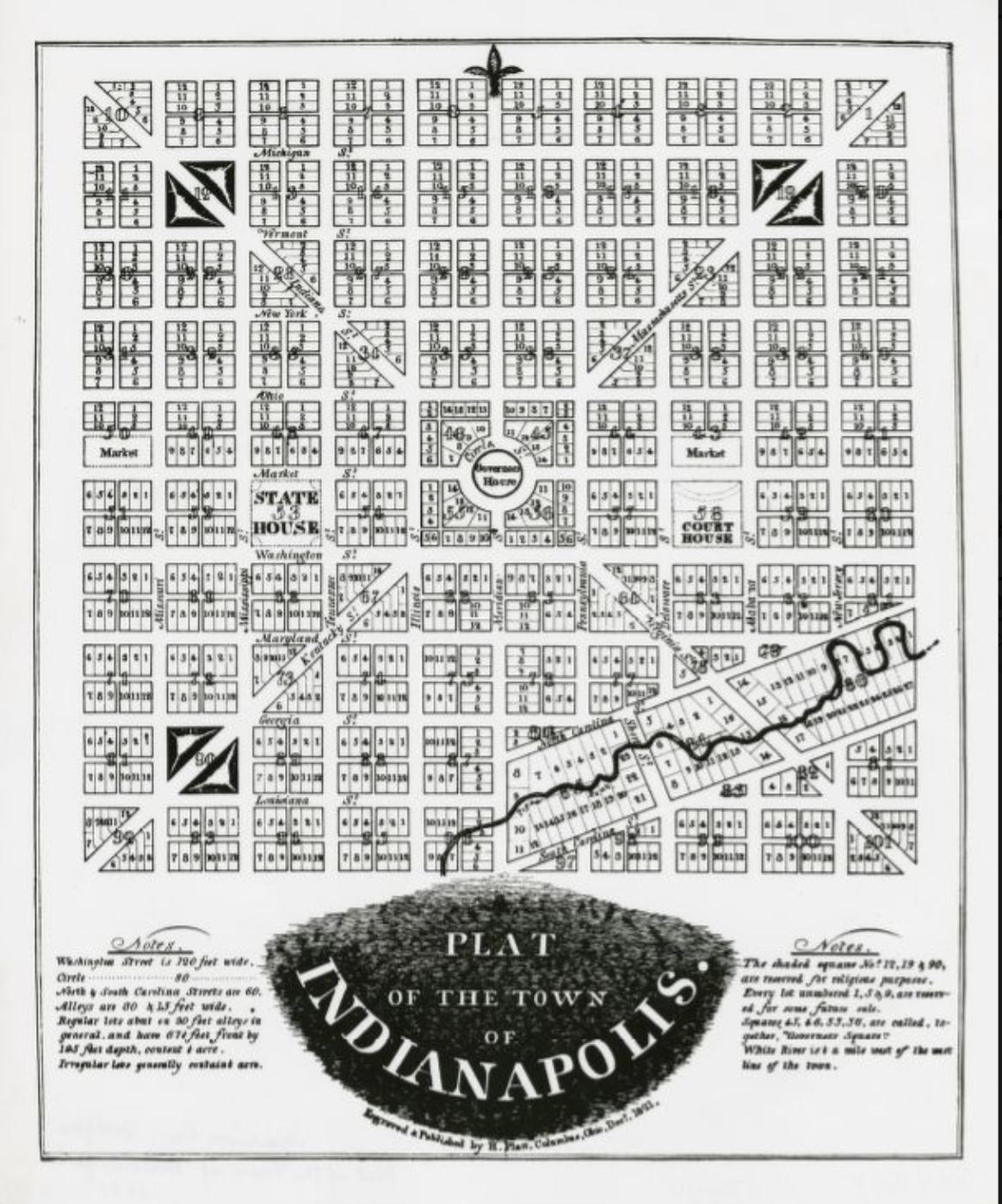

The Mile Square encompasses the area comprising Indianapolis’ original plat created in 1821 by surveyor , who worked under Pierre L’Enfant in the planning of Washington, D.C.

Ralston was chosen by a commission to devise a layout for a capital city for the young state of Indiana in a four-square-mile area of dense forest designated for this issue by the federal government.

Doubting that the city would ever encompass four square miles, Ralston planned one square mile bounded today by North, South, East, and West streets in Indianapolis’ central business district. The Ralston plan is distinguished by diagonal arteries—Massachusetts, Virginia, Kentucky, and Indiana streets (avenues)—connecting the corners of a mile square gridiron with four centrally located blocks.

Unusual in American city planning, diagonal streets derive from Renaissance “ideal cities” that reflected thinking on universal order, and from the baroque period’s use of diagonals to emphasize prominent buildings, monuments, and squares important to a ruling nobility. The most notable applications of diagonals predating the Mile Square are Versailles, St. Petersburg, and Washington, D.C. The plan for Washington by L’Enfant, who was the son of a painter to the royal court at Versailles, uses diagonal boulevards to emphasize points of convergence in the baroque tradition, namely at the Capitol, the White House, and numerous monuments.

Clearly extending this lineage but with much more modest proportions, the Mile Square’s diagonals originally terminated at blocks bounded by Washington, Illinois, Ohio, and Pennsylvania streets, rather than at key buildings, monuments, or squares. This condition was offset, however, with the addition of the in 1901.

Other key features of the original plat include a central circle intended for the governor’s house which subsequently became the location of the monument. Ralston also designated two blocks on Washington Street for the and county courthouse. In outer portions of Massachusetts, Kentucky, and Indiana streets, three additional squares were located for religious purposes. Halves of two blocks on Market Street were reserved for market places. Typical of the era, streets were broad, with Washington Street the widest at 120 feet.

The area in the southeast corner of the Mile Square deviates from the symmetrical gridiron plan. The origin of its irregular layout is unclear, but Ralston may have intended it for uses requiring water (such as mills) or for parkland.

The plan’s impact on Indianapolis’ development was initially sporadic. Early 19th-century development was concentrated on Washington Street between Illinois and Delaware streets. The pre-Civil War introduction of railroads and the location of south of Washington Street resulted in considerable development. These additions offset east-west oriented growth on Washington Street, which had become part of the National Road, and spurred industrial development to the south, residential to the north, and commercial activities around Union Station.

The pattern and location of these land use is virtually intact today, with the Mile Square currently comprising the heart of Indianapolis’ downtown. The principal alteration of the original plan has been the truncation of three of the four diagonals (Indiana, Massachusetts, and Kentucky avenues) so that they no longer terminate at the block surrounding .

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.