The history of city planning in Indianapolis began with the founders’ plat. As the plan for the capital city of Indiana, it was given impressive features not often seen in frontier towns. The original scheme still influences planning in the modern city.

The Mile Square and Early City Planning, 1821-1880s

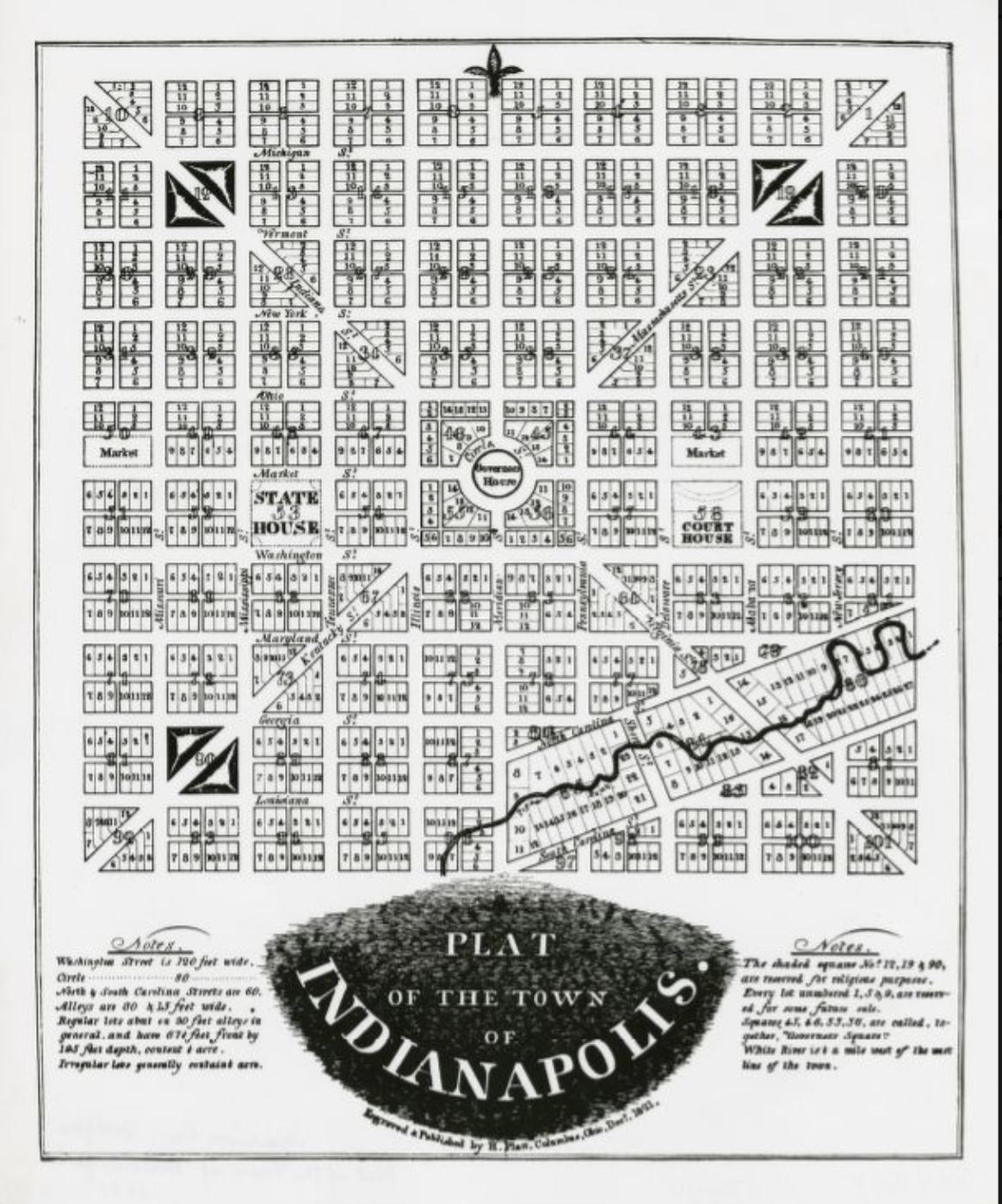

Christopher Harrison, the commissioner charged with laying out the new capital, appointed and as surveyors in April 1821. Harrison and the surveyors immediately devised a plan for the city, and the surveyors had completed their work by October 1821. The plat was roughly square, and each side of the square measured a mile, inspiring the enduring name for the city’s central district. The plan was dominated by a central circular street and four diagonal avenues that radiated from near the center. The circle and the diagonal avenues, which local tradition attributes to Ralston, were imposed on a gridiron pattern of squares and streets.

The planners of the capital anticipated the need for wide streets in the future. They bestowed a 120-foot width on Washington Street, the principal east-west street, and 90-foot widths on the diagonal avenues and other streets. In keeping with the infant community’s purpose, the planners reserved whole or partial squares for government buildings and public institutions: Square, Governor’s Circle, Court House Square, two half-squares for markets, and three squares set aside for “religious purposes.”

Despite this auspicious beginning, no further governmental sponsorship of physical planning occurred in Indianapolis for the next 80 years, while the pioneer settlement grew from a village to a mid-sized city. Additions happened in a piecemeal fashion as individual real estate speculators purchased tracts of land and divided them into plats containing gridiron street patterns and rectangular lots.

The “City Beautiful” Movement, 1890s-1920s

Modern city planning, in which local governments took the initiative in making public improvements, began in the state capital during the 1890s. In that decade the city constructed a new sewerage system and established a park system. After 1900 Indianapolis became caught up in the “City Beautiful” planning movement in which municipalities across the United States undertook extensive improvements to beautify their appearances.

In 1908 the Board of Park Commissioners hired a noted midwestern landscape architect, , to design a system of boulevards to link the city’s principal parks. In 1909 Kessler completed work on an ambitious that would create scenic drives along on the north side of the city, Pleasant Run on the south side, Spades and Brookside parks on the east side, and on the west side. Over the following decade, the park commissioners carried out much of Kessler’s design for Fall Creek, Brookside, and Pleasant Run parkways.

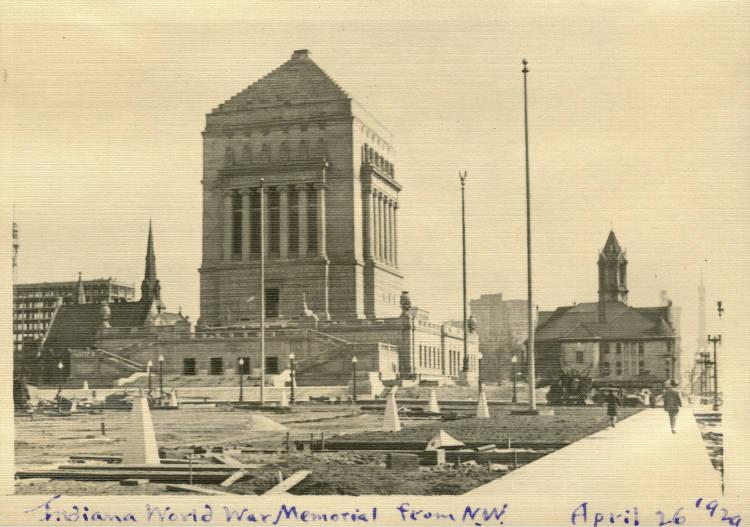

The City Beautiful phase of city planning in Indianapolis reached its zenith during the 1920s with the construction of the north of the central business district. Conceived by the as a memorial to World War I veterans, the plaza took shape over a five-block-long area between New York and St. Clair streets and between Meridian and Pennsylvania streets. The formal plan devised for the plaza by architects Walker and Weeks of Cleveland consisted of a monumental memorial hall, an Obelisk Square, and a two-block-long mall leading to a funerary cenotaph.

Also during the 1920s, Indianapolis joined a national movement to establish city planning as an official function of municipal government. The impetus to create an Indianapolis City Planning Commission in 1921 came from civic leaders concerned over the encroachment of industrial and commercial land uses into areas that had been exclusively residential. In 1922 , executive secretary of the new plan commission, and Robert H. Whitton, a planning expert from Cleveland, devised recommendations for a city ordinance.

The ordinance, which the city council adopted in November 1922, provided for five categories of land use zones. The intention of Sheridan and Whitton was to fix current land-use patterns and provide reassurance for residential property owners that undesirable land uses would not invade their neighborhoods and depreciate their property values. The city plan commission was to adjust the zoning district boundaries in response to changing trends in land use and act as a board of zoning appeals to which owners could petition for variances in the zoning uses designated for particular areas.

City Plan Commission, 1935-1954

In 1935 the Indiana General Assembly passed a “master plan law.” The legislation directed the Indianapolis City Plan Commission to prepare, at least every 10 years, a long-term master plan for public improvements to the city. The 1935 law also authorized the creation of a Marion County Plan Commission, which was to exercise the same powers as the city commission in areas of the county outside the city limits.

The approaching end of World War II in 1943 and 1944 stimulated interest in comprehensive city planning on the part of municipal and business leaders. In 1943 Mayor appointed a to recommend physical improvements that would be needed in a peacetime community. The committee’s report suggested a large-scale, $25 million physical improvement program, to take place over seven years. Despite the endorsement of the report by community leaders, commitment to carrying out its recommendations faded in the economic boom that followed the end of the war.

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, the effectiveness of zoning came into question as city and county boards of zoning appeals granted increasing numbers of variances in the land uses permitted by the zoning ordinances. The attention of public officials was also drawn to the inadequacy of the separate city and county planning and zoning systems in the face of mushrooming suburbs outside the city boundaries of Indianapolis. Master planning done by either the city or county plan commissions could not take into account developments outside their respective jurisdictions.

Metropolitan Plan Commission, 1955-1960s

In 1955 the Indiana General Assembly created a Metropolitan Plan Commission, which combined the responsibilities of the former city and county plan commissions and conducted planning and zoning on a countywide basis. The merger was one of the first of its kind in the United States, and , director of the new Metropolitan Planning Department, represented new thinking among the postwar generation of city planners.

Hamilton became particularly known for the visionary schemes that the planning department advocated for the downtown area of Indianapolis. A downtown master plan prepared by the department in 1958 recommended clearance of large sections of the central city that were declining in property value and their replacement with new public and private developments. Hamilton also called for the conversion of at the center of the Mile Square into a pedestrian mall and the establishment of a “Lockerbie Fair” tourist development in the neighborhood where Hoosier poet had lived. Neither of these plans was implemented.

During the 1960s the Metropolitan Planning Department promoted two large-scale downtown urban renewal projects: a large new state university campus between West Street and White River () and a projected apartment “city” north of North Street on Alabama Street ().

Department of Metropolitan Development, 1970-2020

The expansion of the Indianapolis metropolitan area to the Marion County borders and beyond by the late 1960s helped precipitate the completion of the consolidation of city and county governments that had begun with the creation of the Metropolitan Planning Department. In 1969 the Indiana General Assembly passed legislation that established in which most city and county agencies were merged. The Metropolitan Plan Commission became the ; the planning department became the Planning and Zoning Division of the new (DMD).

In the years since consolidation DMD has turned much of its planning emphasis to preparing individual plans for neighborhoods and parks. Large planned developments of the 1970s and 1980s have included construction of a pedestrian mall along Market Street and Monument Circle, construction of the stadium (replaced with ), partial completion of at the west edge of the downtown, and the downtown. In the late 1980s, DMD, along with the State and community leaders, began the redevelopment of the . The canal was originally constructed in the late 1830s, as a transportation link to move goods.

Although the entire canal was never completed, sections in Indianapolis were developed. For much of its history, the downtown section of the canal was surrounded by a mix of uses, predominantly industrial. In the redevelopment project, the canal was lowered to below street level and improved with sidewalks, fountains, bridges, and other pedestrian-related infrastructure. The properties adjacent to the canal were redeveloped for State office buildings, museums, offices, residential, and accessory uses. The canal is linked to the , a designated cultural district.

The DMD, and its predecessor, The Metropolitan Planning Department, have managed planning for Indianapolis downtown, the Regional Center, for decades. Individual Regional Center plans were developed and adopted in 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2004. A Regional Center Overlay zone was created in 1970. The first Regional Center Design Guidelines were developed as a recommendation from the 2004 Regional Center plan and adopted in 2008. Those guidelines received the American Planning Association’s 2010 National Planning Excellence Award for a Best Practice.

Plan 2020

In 2013, DMD began an effort to consolidate as many existing plans, ideas, and initiatives together into one cohesive vision, Plan 2020. Plan 2020 work was divided into three areas: Setting the Collective Vision, Creation and oversight of the Bicentennial Plan, and Refinement of the Technical City Plans, (Land Use Plan; Thoroughfare Plan; Parks, Recreation, and Open Space Plan; Regional Center Plan; Housing and Urban Development Consolidated Plan; and Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy). Plan 2020 had an extensive community engagement process that used 12 engagement tools and reached approximately 114,000 people.

In 2017, DMD created the People’s Planning Academy to help residents and stakeholders understand the planning processes and empower them to take a more active role in the shaping of their community. The Academy’s first sessions were in preparation for the update to the land use plan. A second session, focusing on Transportation, was offered in 2019. For each program (2017 and 2019), six sessions were offered twice. The sessions were also recorded and made available to the public. In 2019, The American Planning Association awarded the People’s Planning Academy its Gold National Planning Award for Public Outreach.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.