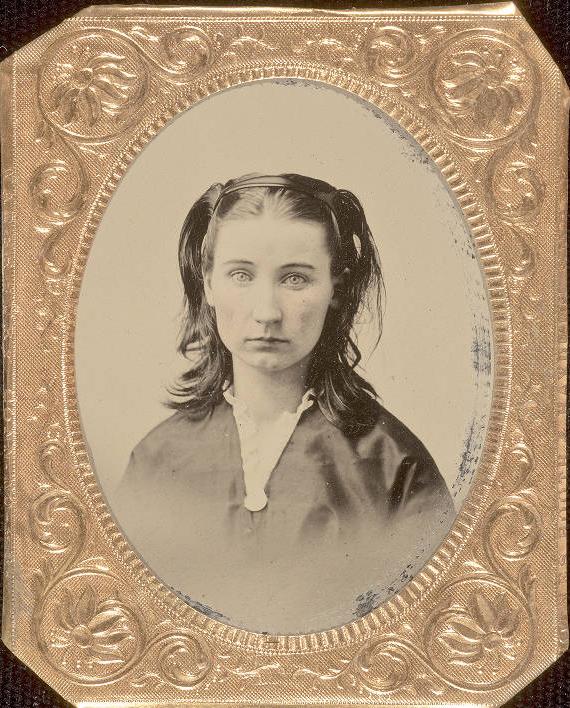

Photo info ...

(May 27, 1844-July 22, 1920). Born in Greenfield, Wisconsin, May (Mary Eliza) Wright Sewall taught in school before entering North Western Female College at Evanston, Illinois, where she received the laureate of science degree (1866) and an honorary master of science degree (1871). She and her first husband, Edwin W. Thompson, moved to Franklin, Indiana, in the early 1870s, where he served as superintendent of schools and she was named principal of the high school.

The couple came to Indianapolis in 1874 to teach at Indianapolis High School, but Edwin died the following year. In 1880, she married Theodore Lovett Sewall (1852-1895), who had established the Indianapolis Classical School for Boys. The prestigious Classical School for Girls, which they opened in 1882, gained an excellent reputation for academic work and prepared many young women for eastern colleges.

With , wife of former Governor David Wallace, Sewall helped found the Equal Suffrage Society of Indianapolis. Because of strong anti-suffrage feelings in the city, suffrage advocates had to meet in secret to form the organization.

As a delegate of the local and state societies, Sewall attended her first national suffrage meeting in 1878 in Rochester, New York. There, she met suffrage leaders Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and others with whom she began to work at the national level.

In Indiana, she participated in the suffragists’ efforts in the early 1880s to amend the state constitution, presiding over a mass meeting at the Grand Opera House that appointed delegates to attend the state political conventions and attempt to persuade legislators to give women the vote. From 1882 to 1890, she was chair of the executive committee of the National Woman’s Suffrage Association (NWSA).

Sewall’s interest in women’s rights broadened when the NWSA, in 1888, sponsored a meeting of national and international organizations. From this meeting came “the Council idea,” for which Sewall is credited. Stanton suggested the international meeting in 1888, but it was Sewall who envisioned a permanent organization of national councils of women from many nations.

She served as president of the National Council of Women of the United States from 1891-1895 and from 1897-1899. From 1899 to 1904, she was president of the International Council of Women. At the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, she developed a special congress for women and brought together outstanding feminists from the United States and abroad. In 1900, President William McKinley appointed her as a Special Representative to the Congress of Women at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, representing the organized work of U.S. women.

Sewall contributed significantly to the civic and social life of Indianapolis. In 1876, she was one of the founders of the and, for many years, was an officer of the , the predecessor of the (Newfields). The Indianapolis , built in 1890, resulted from her idea two years earlier for a club building to be owned and managed by women. Sewall also was a founder of the , the Indiana branch of the Western Association of Collegiate Alumnae (a forerunner of the Association of American University Women), the Local Council of Women, and the Alliance Francaise.

Her interest in peace began as early as 1895. She chaired the International Council of Women’s standing committee on peace and international arbitration from 1904 to 1914. In addition to her speeches and writings for international understanding and cooperation, she organized a women’s conference at the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco in 1915. Later that year, she sailed to Europe on the much-ridiculed Henry Ford Peace Ship.

Sewall left Indianapolis in 1907 after the sale of her school, living for the most part in New England, writing and lecturing. In 1919, in ill health, she returned to the city. Shortly before her death, the published her book on spiritualism, (1920), which described her conversations with her deceased husband Theodore and other psychic experiences.

After her death, a May Wright Sewall Memorial Fund was established to place books in the public library in her memory, and two bronze standards were erected to light the entrance to the . These have since been moved to the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.