Indianapolis experienced profound changes during World War I. The societal transformation was marked by widespread community service and patriotism, cultural intolerance and discrimination, and an overall spirit of purpose and industriousness.

Prior to the United States’ entry into the war, portions of the Indianapolis community participated in the emerging peace movement. The city hosted the Indiana Peace Society in March 1915, which met to coordinate efforts among other peace organizations. Later in the year, Stanford University president David Starr Jordan, a former professor, lectured for the World Peace Foundation, and joined Henry Ford’s ill-fated peace mission to Europe in December 1915.

Isolationist attitudes prevailed in Indianapolis as residents showed little concern over potential threats to American security. Leading the drive for military preparedness, however, were well-known Indiana authors , , George Ade, William Dudley Foulke, and . Local Progressive reformer also advocated a larger military force and presented an anti-German polemic at the in October 1915.

Although Hoosiers supported the Allied cause by 1916, it was not until 1917 that concerns about German military actions stirred local residents. of the wrote that the war was “one between civilization and barbarism, and we should stand for civilization.” On March 31, 1917, a mass meeting chaired by Episcopal Bishop Joseph M. Francis at urged Congress to declare war on Germany.

Following the U.S. declaration of war, most Hoosiers closed ranks behind the war effort. The , previously an antiwar paper, urged all Americans to support their nation’s cause. Local German Americans threw their support behind the Allies. Columnist of the wrote “Long Boy,” “The Kid Has Gone to the Colors,” and “We Are Coming, Little Peoples,” poems set to music to rally public sentiment.

The Marion County Council of Defense, reporting to the Indiana State Council of Defense (established May 1917), served as the city’s umbrella organization for war activities. Chaired by John M. Judah, a prominent businessman and lawyer, and secretary Russell B. Harrison, son of former president Benjamin Harrison, the council consisted of seven citizens including , founder of the and the Union Trust Company, and James Fesler, an attorney and Indiana University Board of Trustees president. Though tension occasionally existed between the county and state councils, the organization nonetheless succeeded in coordinating widespread support on the home front.

Indianapolis women contributed enormously to the local effort. They first began a “socks for soldiers” campaign, knitting thousands of socks for Indiana regiments departing for France. The County Council of Defense established a Women’s Section to oversee programs ranging from volunteer registration drives to the local Liberty Kitchen, a successful program to assist women in minimizing their use of meat, wheat, sugar, and fat in food preparation. The Patriotic Gardeners Association of Indianapolis made significant contributions to the food economy by placing more than 70,000 home and vacant lot gardens under cultivation. The Child Welfare Committee sponsored clinics to raise health care standards, while other women collaborated with organizations ranging from the Red Cross to the YWCA’s War Work Council.

Local businesses and industries also geared up to join the cause. The opened a war contract bureau to provide information regarding government contracts. manufactured munitions; and Allison Engineering made airplane engines; Indianapolis Gas Company converted some operations to produce explosives; and supplied military uniforms.

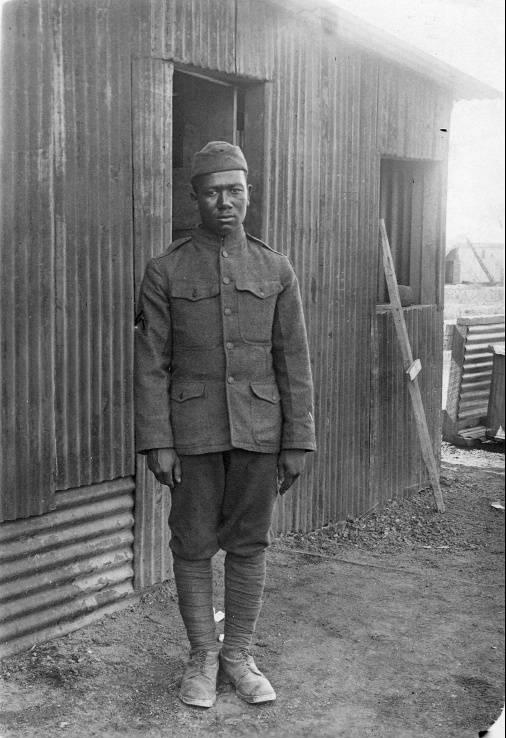

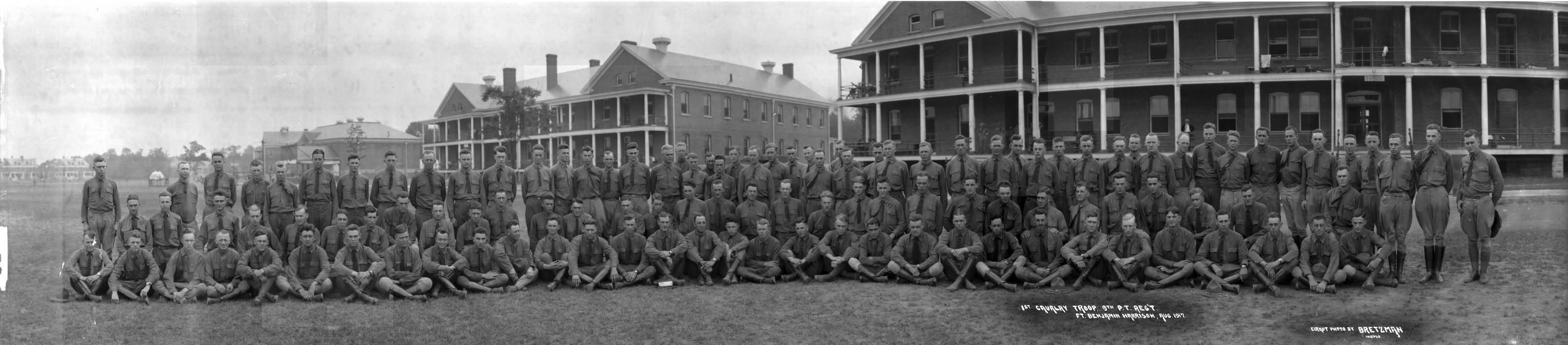

Indianapolis played an important military role in the war. Though most Indiana conscripts trained elsewhere, hosted Army officers in two training camps from May to August 1917, and a third camp from August to November 1917. Though racist attitudes initially excluded African Americans from early recruiting efforts and serving in combat units, they volunteered and did see action during the war. Despite facing continual discrimination and segregation, African American troops loaded cargo, constructed roads, and camps, transported materials, dug graves and ditches, laid railroad tracks, and fought at the front.

Specialty camps conducted at the fort attracted approximately 10,000 troops to receive instruction as engineers and railroad specialists; over 6,000 officers and enlisted men were trained in medicine. mobilized at the fort in September 1917 and served in Contrexeville, France while staffed by local doctors and nurses. General Hospital No. 25 opened in September 1918 for the treatment of “shell shock” victims.

Vocational camps commanded by military officers were established at the Hotel Metropole and the state schools for the blind and the deaf. Men received training in gunsmithing, engine mechanics, and blacksmithing, and some became known as the “Blue Overalls Detachment” as they hiked to city schools and local shops where they received training.

Indianapolis automobile industrialist tendered a machine shop to the government for the production of aircraft parts, and the was converted into an airport to serve as a cross-country refueling station and major repair depot.

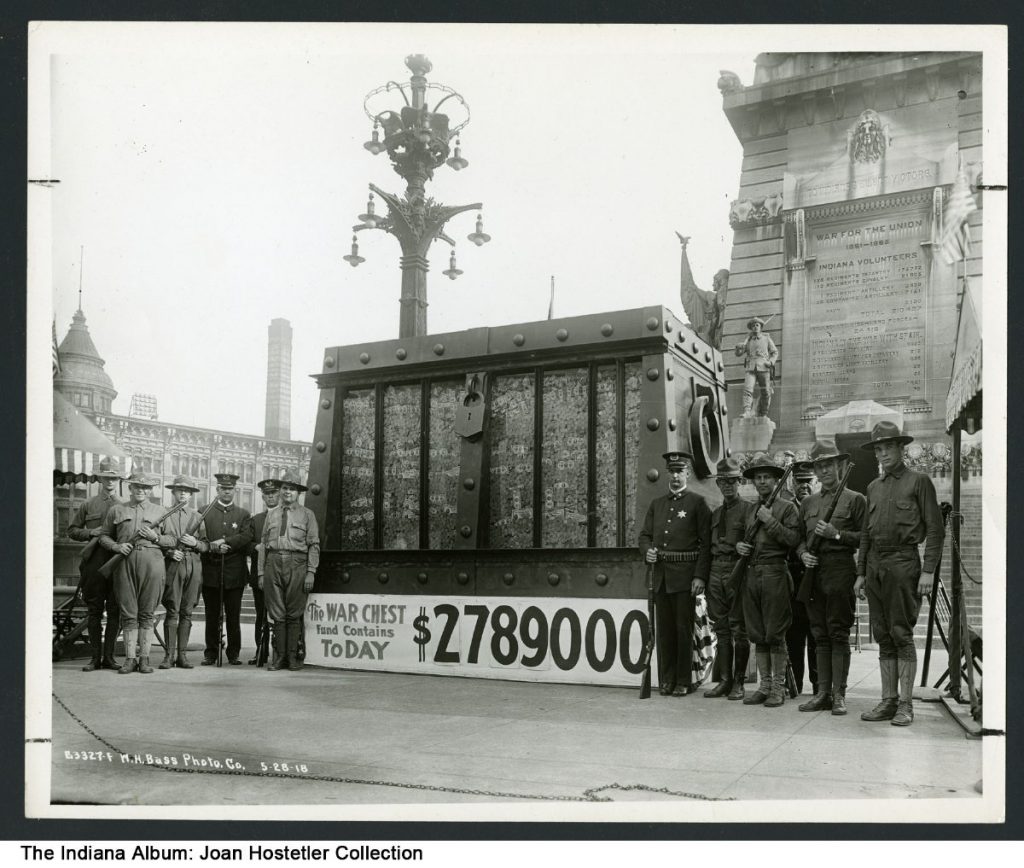

As was true elsewhere, Indianapolis subscribed to Liberty Loan campaigns and promoted the sale of War Savings Stamps and Red Cross subscriptions to aid the expensive war effort. Local businesses encouraged employees to buy bonds. The Boy Scouts and churches also joined in various campaigns. By July 1917, residents had donated over $500,000 to the Red Cross. One loan drive in May 1918 generated $15 million in contributions. During the fourth Liberty Loan drive in October 1918, Marion County surpassed its $23.4 million quota by $682,000.

Patriotism also was an important component of the war effort, and local authorities made strong attempts to encourage nationalism and suppress dissent. The war spawned over 35 patriotic organizations, and residents met frequently for rallies, noontime community sings on , and parades. A crowd of 200,000 lined downtown streets in August 1917 to honor the 150th Artillery Division, commanded by Col. , as it departed for Europe. Both the editorials and general reporting of local papers were unequivocal in their support of the Allies. Patriotism could scarcely be described as voluntary, however, mechanisms were soon imposed to ensure it.

The State Council of Defense requested the creation of local “Protection” committees to communicate directly with federal law enforcement agents regarding disloyal neighbors and questionable activities. Governor James Goodrich established the paramilitary “Liberty Guards” in December 1917 to keep order and eliminate subversion at the county level.

The Indianapolis Common Council passed Ordinance No. 35 of 1917, outlawing disloyalty to, disrespect for, or defiance of the government, the president, and the armed services. The council also made it unlawful to “incite, urge or advise strikes or disturbances” in war-related factories. In 1918, the council adopted Ordinance No. 11 against “war loafers,” those not engaged in lawful employment or who spent time in the streets. Overlooking constitutional protections for the freedom of speech, city officials encouraged citizens to report neighbors who demonstrated any sort of disloyalty or pacifism.

The State Council’s Education Section reported that it had taken “particular pains. . .to bring to the public schools lofty and reliable messages of impartial attachment to the principles at stake in the war.” Throughout Marion County, most schools reportedly spent 10 to 30 minutes daily on “patriotic exercises” or producing articles for soldiers. Over 40,000 school children marched in 65 parades around the city in June 1918 to sell War Savings Stamps. To discourage dissent, the Indianapolis school board added a loyalty clause to teachers’ contracts in 1918-1919.

Indianapolis’ German population and its institutions bore a disproportionate share of the suspicion fostered by zealous patriots. Before the United States entered the war, many local German Americans sided with their homeland, called for the United States to cease munitions sales, and even organized to help local residents return to Germany to fight. After the declaration of war, most joined in support of the Allied cause.

Even so, individuals and groups who associated German heritage with disloyalty to the United States targeted the German community for attacks. The printed names and addresses of 800 unnaturalized Germans; anti-German rhetoric was fierce among local leaders; and many German cultural institutions became targets of vandals. In response, these organizations anglicized or changed their German names. (Das Deutsche Haus, for example, became the .) Even the German-language newspaper ceased publication.

Despite serious legal concerns, language instruction in German was banned in elementary schools beginning in January 1918. Still, the local German-American community raised funds for the Allied effort, passed proclamations declaring their loyalty, and even formed a company of the state militia in hopes of fighting against the Kaiser. , a local German-born businessman and military secretary to Governor Goodrich, helped to rally German Americans for the U.S. cause.

On November 7, 1918, a United Press bulletin, released by former Indianapolis newspaperman , announced an armistice. News of the actual armistice signing reached the city in the early morning of November 11, 1918, beginning days of celebration.

A massive homecoming for Hoosier soldiers was held on Monument Circle on May 7, 1919. As the city began to readjust to the liberties and pleasures of peacetime, the newly established (November 1919) selected Indianapolis for its national headquarters, and plans were made to construct the to honor the nearly 3,400 Hoosier soldiers (approximately 350 from Indianapolis) who did not return home.

The war stimulated internationalist sentiments in many quarters. Local supporters of the movement to create the League of Nations included Foulke, Howland, and Tarkington. Both the and moderately supported American involvement with the Allies to preserve the peace. Others, including former U.S. Senator and Swift, spoke against the League, fearing the loss of national sovereignty. Meanwhile, the city began to reconvert its industries to peacetime production, and Indianapolis residents, in general, regained their isolationist attitude.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.