People with ancestral ties to Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, and other German-speaking provinces of central and eastern Europe constitute the largest white ethnic group in Indianapolis and have since the city’s formative years. The first large influx of German immigrants came following the Revolution of 1848. There were 1,045 persons of German ancestry (802 German-born, 243 of German parentage) in Indianapolis in 1850, or 12.9 percent of the total population.

Events in Europe always influenced German immigration. Except for the Harmonist settlement (1814-1824) in southwestern Indiana, early immigration to Indiana occurred during the post-Napoleonic period (1815 -1848). The peace following Napoleon’s defeat did not bring prosperous times. Economic hardship, loss of liberty under an authoritarian government, and the forced merger of Lutherans with the Reformed churches in Prussia all served as an impetus for religious and conservative German families to immigrate to America.

Arrivals in Indianapolis after the democratic revolutions of 1848 were generally well educated, liberal, anti-clerical, and dedicated to applying their ideals of freedom and progress through education to their adoptive country. They believed that American democracy reflected their own ideals of individual freedom combined with social responsibility. Even after settling in America, ethnic and cultural homogeneity was not a given, especially in urban areas. Germans organized Vereine (societies) and churches to maintain their ethnic identity and provide for the mutual assistance of fellow countrymen. They, however, tended to be identified either with the church kirchendeutsch, or church German) or with the more secular lodges (vereinsdeutsch, or club German), which contributed to the diversity and fragmentation of the community (see ).

Many German residents were dedicated to the teachings of Friedrich Jahn (1778-1852), a political liberal and “father” of the Turner movement that espoused the classical ideal of mens sana in corpore sano (a healthy mind in a healthy body), a motto engraved on the on North Meridian Street. Several young progressive followers of Jahn—August Hofmeister, , and John Ott, all future prominent and prosperous civic leaders—established the Indianapolis Turngemeinde (later Socialer Turnverein, and then Athenaeum Turners) in 1851 (See also ).

Another indicator of a vibrant culture was the , established as a means of communication and cultural preservation for the growing population. The first journal was the conservative , founded in 1848 by Julius Boetticher. Its progressive counterpart was , edited and published by Theodore Hielscher beginning in 1854. Over time Indianapolis had 26 German-language periodicals, some of which reported remarkable circulations (nearly 11,000 for the in 1910).

German Americans played a strong part in the development of the arts in Indianapolis. The oldest continuously existing men’s choir in the United States was the Indianapolis , founded in 1854. Under directors Eduard Longerich, , and Alexander Ernestinoff the chorus received wide acclaim. (The Maennerchor continued to operate until April 2018.)

By the 1860s, German immigrants and their offspring had become an integral part of the Indianapolis business community. Clemens Vonnegut Sr. established a hardware business, Henry and August Schnull a wholesale grocery, John Ott a furniture business, Peter Lieber a brewery, Hermann Lieber an art supplies and frames store. George Meyer dealt in wholesale tobacco products, Wilhelm Langsenkamp established a train repair business, and Albrecht Kipp dealt in wholesale products.

During the , the Indianapolis German community actively opposed slavery, favored the Union, and volunteered in large numbers to fight for the new fatherland. The Freimaenner Verein (Freemen’s Society) agitated against slavery from the early 1850s, while the liberal, activist Turners advocated the necessity of opposing the Confederacy.

Prominent Germans received permission from Governor in 1861 to establish the 32nd (First German) Regiment, commanded by General August Willich, which served with distinction at Shiloh and Missionary Ridge. The Germans’ role in the Civil War was indicative of their relationship to their new country. German intellectuals, if not the greater majority, believed that since the United States was still in its formative stage, they had a particular role in infusing the best of their own cultural and intellectual traditions into the American mainstream.

The area bounded by New York, Noble (College Avenue), Market, and East streets was known as “Germantown” because of the concentration of Germans living there, but German Americans, hardly comprised a monolithic group and were more diverse than, for example, the . Consequently, they never functioned as a cohesive political or social unit. Originating in provinces that had very diverse cultures, Germans retained their regional loyalties even after German unification in 1871. There were also religious differences: Protestants of various persuasions from the North, Catholics from the Rhineland and Bavaria, Anabaptists from southwest Germany and Switzerland, and Jews from urban areas. Unlike in Cincinnati, German immigrants to Indianapolis did not maintain a distinctly German section of the city in the decades following their first arrival.

By 1875, there were 91 German American businesses in the three blocks on Washington Street between Illinois and Delaware. German Americans were also involved in banking and capital ventures, such as the Frenzel family and (1865). One of the state’s largest insurance firms was the German Mutual Insurance Company (1854). On a smaller scale, mutual aid societies (Unterstuetzungsvereine) helped small businesses and families in need. Although now less important for their financial activities, four German American mutual aid societies remain in Indianapolis.

The social service infrastructure of Indianapolis also felt the impact of the German presence. Concern for Civil War orphans resulted in the founding of the (1867). German Americans also helped establish and the . Reverend Christopher Peters of Zion Evangelical Reformed Church (now Zion Evangelical United Church of Christ) organized the Protestant Deaconess Society in January 1895, which later established Deaconess Hospital with its nurses’ education program, and the (Altenheim Retirement Community).

The Germans’ emphasis on preserving their intellectual and cultural traditions affected the development of education in Indianapolis. Liberal-minded German Americans, including Valentine Butsch and Adolph Seidensticker, who sought an alternative to inadequate public schools and German Lutheran and Catholic parochial schools, established the in 1859. It survived until 1882 when parents considered public schools sufficiently improved and German instruction was made available.

By 1900, Indianapolis was a center for German language pedagogy, and the major second language was German. Dr. Robert Nix, author of numerous textbooks, served as director of German language instruction for the city schools (1894-1910). New industrial training schools, based upon the German Gewerbeschule, originated through active lobbying by the German community. , an active , was the first principal of , which was later renamed for him. Prominent “vereinsdeutsch” freethought. Philosopher Clemens Vonnegut served as head of the Indianapolis School Board for many years.

Germans continued to contribute to the arts in the last decades of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Karl Schneider founded a local symphony orchestra in 1895. Hermann Lieber, a great patron of the arts, made it possible for artists of the “Hoosier Group,” including and , to study in Munich and get their start back home. Wilhelm J. Reiss, who arrived in Indianapolis from Berlin in 1884, painted scenes of the West and Indian life.

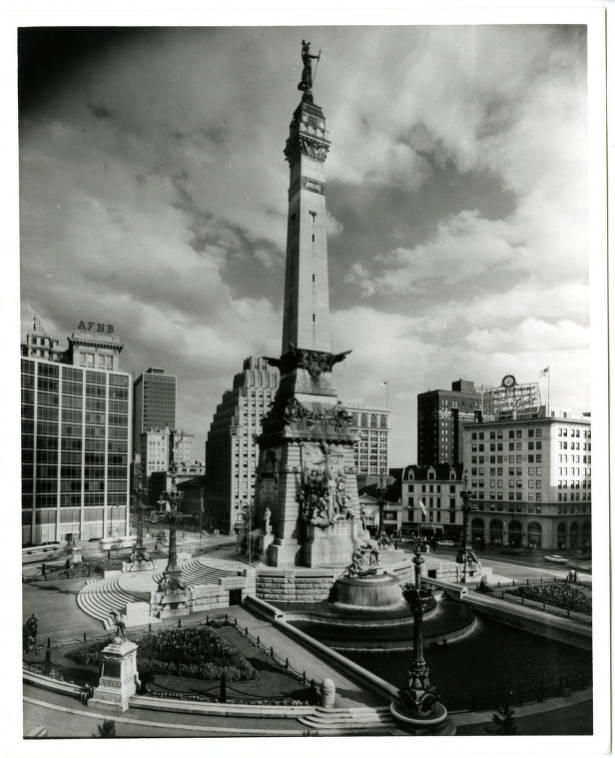

Architects of German origin designed many of the city’s churches and public buildings. , of Swiss-German origin, completed the design of the present Indiana . George Schreiber designed the . The architectural firm of was responsible for the and the , among others. (later D. A. Bohlen & Son) designed many public buildings, including , , the , , and the . Bruno Schmitz of Berlin designed the , the tallest such monument in the United States at its completion in 1902; created the accompanying sculptures depicting Civil War scenes.

In 1907 the , which promoted physical education in school curricula nationwide, moved from Milwaukee to Indianapolis. The college became a part of Indiana University in 1941, making the School of Physical Education of Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis the oldest in the United States. Later renamed the School of Physical Education and Tourism Management, it merged with the IUPUI School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences to become part of the School of Health and Human Sciences in December 2017.

Around 1910, there were 56 German societies in Indianapolis providing social, cultural, and educational opportunities. Only 16 societies, or 17 including the , an umbrella organization to which 13 societies belong, existed in 1993. The Federation and the German American Klub have maintained headquarters in on South Meridian Street since the 1930s. The Indiana German Heritage Society, a statewide organization located in Indianapolis, was formed in 1985 and supports research on German Americans.

Reflecting the desire for religious self-determination, inspired in part by the religious persecutions in Prussia, Germans contributed to the diversity of religious life in Indianapolis. Many churches claim a German American heritage, including First Lutheran, Zion Evangelical U.C.C., Friedens U.C.C., St. John’s Lutheran, St. Peter’s Lutheran, Emmaus Lutheran, St. Paul’s Lutheran, St. Mary’s Catholic, Sacred Heart Catholic, and First German Evangelical Church (which later became the Lockerbie Square United Methodist). Congregations like Ebenezer Lutheran (1836-1970s) and Mt. Pisgah (1837, later First) Lutheran date from Indianapolis’ earliest German settlement. Relative latecomers are the Mennonites (1951) and the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod (Divine Savior Lutheran Church, 1971).

In the early 1900s, German Americans suffered three distinct blows to their way of life: , Prohibition, and the Great Depression. World War I brought German Americans into direct conflict with the Anglo-American majority, who used the occasion to seek a leveling of overt German cultural influence. Such chauvinism was reminiscent of nativistic outbreaks witnessed as early as the 1840s.

To maintain the economic and other gains they had made, and since they had become a part of “mainstream” society, many German Americans abruptly stopped using the German language. The war had a highly disruptive effect on social activities and in some instances on family life. had a further deleterious effect by removing a staple from their social and economic lives. Economically, like all Americans, local German Americans suffered from the effects of the Depression. Immigration from Hitler’s Germany during the 1930s and the subsequent postwar period added to the city’s German population.

Over the decades the German-born population declined while the ancestral population grew steadily. The 1870 census listed 6,536 German-born in Marion, and the 1890 enumeration counted 19,154 residents of German ancestry (18 percent of the population). In 1990, nearly one-quarter of Indianapolis’ population claimed German ancestry—175, 101 individuals of German ancestry (23.6 percent of the total population), the largest proportion for any ethnic group. By 2018, with increased diversification and an overall drop in the white population, the Demographic Statistical Atlas listed 133,000 individuals with German ancestry, making up 15.7 percent of the city’s population.

Although that percentage has dropped, people of German ancestry still constitute a significant part of the population. German business interests, such as , added a new dimension to Indianapolis’ relationship to Germany. The 150-year presence of Germans in Indianapolis continues to be evident through their numerous festivals and celebrations. Oktoberfest in German Park, the Athenaeum Turners’ St. Benno Fest, the concerts, dances, and dinners sponsored by the , and , and the observance of German American Day on October 6th all reflect the strong German heritage of the urban population. Indianapolis and Cologne have established a sister city relationship that provides an official link to a major German city. German continues to be taught in almost all of the township schools, in some of the Indianapolis Public Schools, and all of the city’s major colleges and universities, testifying to the continued impact of German immigrants since the 1840s.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.