Indianapolis has long been home to a variety of museums, many of them nationally acclaimed. These museums provide the community with both recreation and education. A few originated in the 19th century, but most developed and flourished during the 20th century. Their development paralleled that of museums nationwide, with public-spirited community leaders, museum pioneers, and major benefactors working together to create outstanding institutions.

Establishing museums and other cultural institutions was not a priority for early Indianapolis settlers. By the time Indianapolis museums emerged, strategies for museum management, funding, and education had matured. In fact, most historians believe that museums took their modern form during the watershed decades of the 1870s and 1880s, the very years that witnessed the early development of Indianapolis museums. By that time, museums had generally become more professional and educational and had abandoned excessive forms of entertainment. They had abandoned their total dependence on a paying public as well. Instead, they were formed by public-spirited citizens (a growing number of them women) who were intent on educating the community and who understood that major collections could be financed in part by the growing fortunes of industrialists and wealthy community members.

Like other larger industrializing cities, Indianapolis was developing a class of business and community leaders whose newly acquired wealth would soon serve as the foundation for museum collections, buildings, and publications. One of its most prominent institutions, the Indianapolis Museum of Art (IMA, see ), originated as the , founded by in 1883. Thanks to the active promotion of art by Sewall and others, John Herron, an English immigrant who had settled in Indianapolis, bequeathed the Art Association close to a quarter of a million dollars to build an art school and museum in his name.

One of the oldest Indianapolis institutions found new direction and stability during the important decade of the 1880s. The (IHS), established in 1830, had faltered for over 50 years, lacking both active leadership and interested membership. But in 1886, shortly after the founding of the Art Association, and others revamped the IHS.

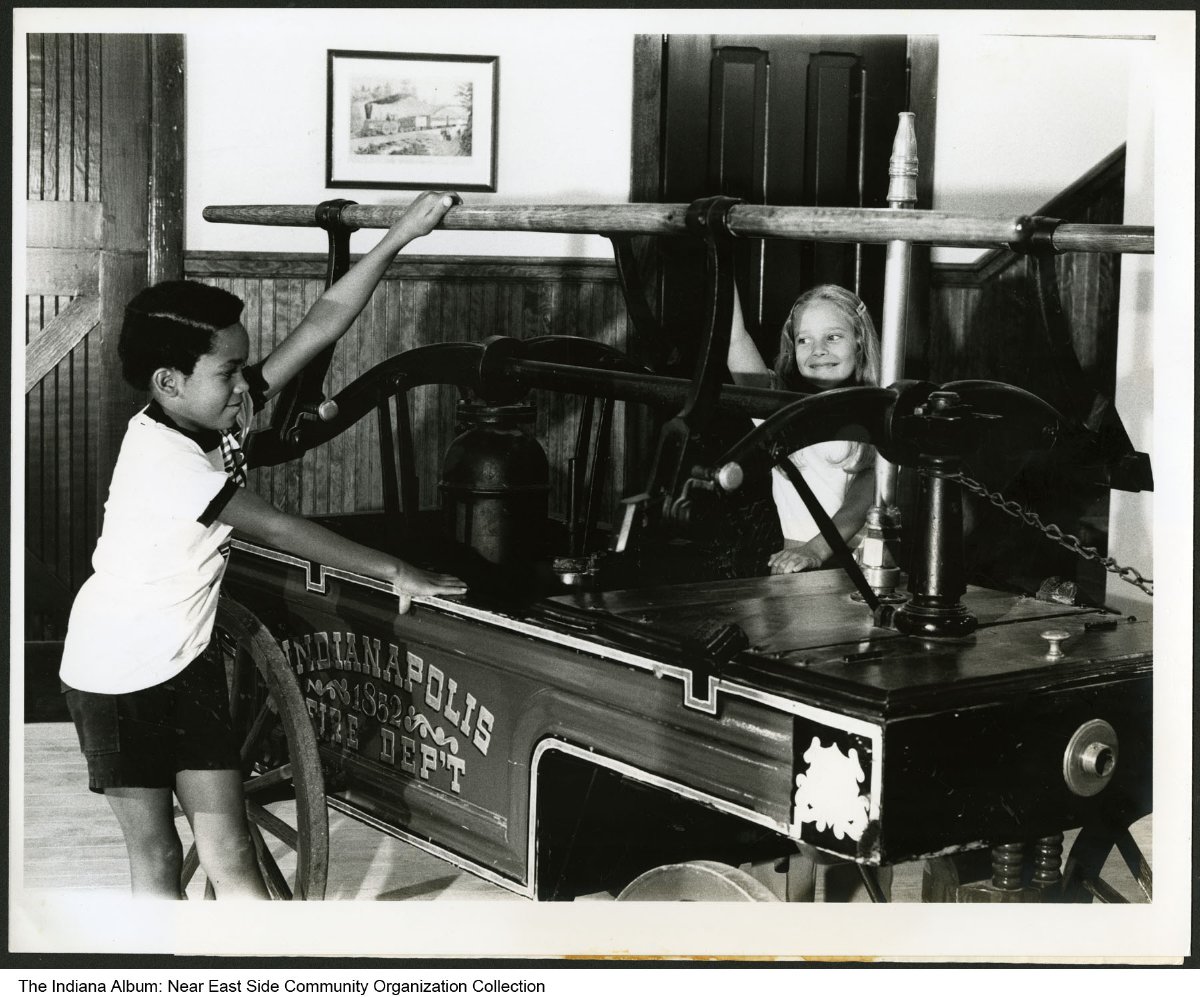

The IHS and IMA stand alone as successful cultural institutions in the 19th century. Although the was established as early as 1862, the absence of a permanent location doomed it to secondary status for almost a hundred years.

During the first half of the 20th century, a number of newly created Indianapolis museums joined the IHS and the IMA as cultural and educational landmarks. All relied on visionary founders, generous benefactors, and highly motivated, public-spirited citizens. For instance, (1926) was pioneered, like the Art Association, by a resourceful woman determined to launch an institution that would serve the people of Indianapolis. not only proposed the idea of a children’s museum but garnered support among benefactors and fellow advocates who helped fund it.

Similarly, purchased the house in which , the Hoosier poet last resided, soon after he died in 1916. Fortune held it in trust and gave it to the Riley Memorial Association (later renamed [RCF]), established by a score of writers and Riley admirers. RCF has operated the as a memorial since 1922.

Although public-spirited individuals and generous benefactors were central to most museum ventures in Indianapolis, one family—and especially one man—looms large as a major force in vision and funding for many cultural institutions. , businessman and philanthropist, contributed countless resources to a number of museums in the greater Indianapolis area, as did his wife, Ruth. The Lillys’ involvement in the city’s museum community was so extensive that few institutions were untouched by the family’s generosity.

Lilly’s range was remarkable. A long-time advocate of Indiana’s history, he served on the Indiana Historical Society’s board of trustees and bequeathed a portion of his estate to the organization. This gift allowed the IHS to develop into one of the preeminent state historical societies in the country, with a significant library and a sophisticated publications program. Lilly’s interests also encompassed historic preservation.

In 1934, Lilly purchased the deteriorating house, on the site where state commissioners had met to determine the location for the new capital. Influenced by Williamsburg, Lilly hoped to recapture some of Indiana’s pioneer heritage by restoring the Conner House and occasionally opening the grounds to the public. Eventually, he presented the house and property to Earlham College, which incorporated them into , the area’s first living history museum.

Lilly also purchased the , a property he had long admired, restoring and furnishing it in 1962. He helped endow (1960) and provided additional money for the organization to purchase the . Then he and Ruth helped to furnish the 1864 structure like a house museum, which it functioned as until 2013 when it was converted to a venue space.

Other Lilly family members also contributed to the financial health of Indianapolis-area museums. The descendants of , donated Oldfields, the family estate, to Newfields. On several occasions, Ruth and Eli each donated funds to the IMA, and Ruth Allison Lilly actively supported The Children’s Museum. The Lillys’ influence was so great that the , founded in 1959 at New Haven, Connecticut, relocated to Indianapolis 30 years later in large part due to the proximity of the , the private foundation funded by the family in 1937.

Even when other benefactors provided the catalyst for new museum creations, the Lillys or the Lilly Endowment usually became involved. For instance, Indianapolis businessman donated his important collection of western art to what would become the (1989). At the same time, he contributed funds designated for the construction of the museum building. To complete the construction of the architecturally significant building, the museum relied heavily on resources from the Lilly Endowment.

The Lilly family and the Lilly Endowment have not been the only forces responsible for the development and transformation of Indianapolis museums. Major changes in historical thinking also have inspired and refocused the interpretive framework for many museums since the 1970s.

The burgeoning field of social history profoundly influenced several museum presentations. Important insights by social historians have served as the basis for interpretive efforts at Conner Prairie and , an organization of African American interpreters who portray the Black experience in Indianapolis in the 1870s and beyond.

The began concentrating not only on important physicians and medical institutions but also on the social impact of disease, medical education, and medical ethics on the larger community. Historically, house museums have often been utilized as stages for narrowly highlighting the one important man, woman, or family who lived in the structure. But their interpretive focus within the last 20 years has been directed toward larger issues.

The , while delving into the life of the Hoosier president, began interpreting broader issues within the political culture of the 19th century.

Like the city itself, many museums launched building campaigns in the 1980s and 1990s. A variety of institutions including the , Conner Prairie, the , and the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art, —to name only a few—built new structures and, since 1990, others made plans to move into the White River State Park area or began to develop plans for larger facilities elsewhere. In 1999, the Indiana Historical Society moved into a new building off of the Central Canal near the park, and the Indiana State Museum broke ground at its new site within the park. In 2000, the NCAA opened its Hall of Champions with two levels of interactive exhibits became another attraction there.

New museums continue to call Indianapolis their home. The opened in May 1998 on the campus of Crispus Attucks Medical Magnet High School, celebrating the history of Indianapolis’ Black community. Bringing the beat, the Percussive Arts Society moved their headquarters and museum to Indianapolis, opening Rhythm! Discovery Center in 2009. Celebrating one of Indianapolis’ treasured icons, the was established in 2011.

Most not-for-profit museums in Indianapolis have been accredited by the American Association of Museums, and most have professional staff. As these staffs assume more educational responsibilities, and as the educational missions of museums become even more pronounced, Indianapolis museums will continue to play a role in the cultural life of the city.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.