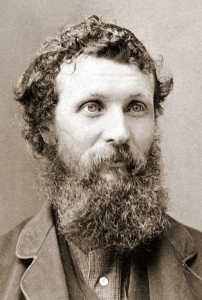

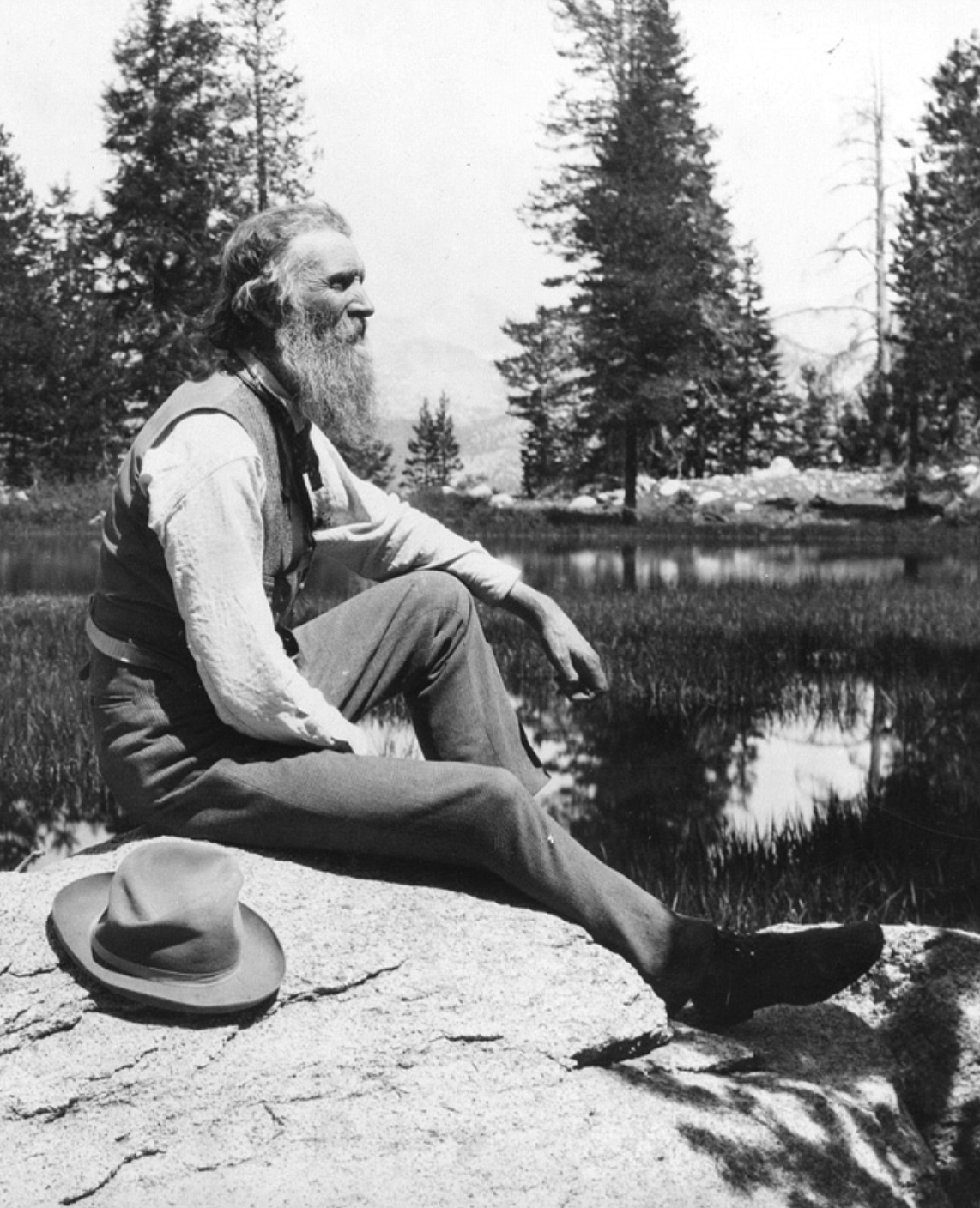

(Apr. 21, 1838-Dec. 24, 1914). Born in Dunbar, Scotland, John Muir immigrated with his family to the United States in 1849, settling on a farm near Portage, Wisconsin. In the fall of 1860, Muir exhibited several mechanical inventions at the Wisconsin State Fair. Although his formal education ended at age 11, he was able to gain admission to the University of Wisconsin in 1861 on the strength of his designs. In 1863, Muir left the university without a degree and began the first of what would be a series of foot tours of the United States dedicated to the study of nature. In March 1864, Muir went to Canada to avoid the draft.

At age 28, Muir returned to the United States and settled in Indianapolis. He chose the capital because of its industrial potential and the fact that it was surrounded by forests of deciduous hardwoods. From April 1866 to March 1867, he worked for Osgood and Smith, manufacturers of the Sarven carriage wheel. Initially hired as a sawyer, Muir was soon promoted to foreman and made several mechanical innovations in addition to doing a time-and-motion study to determine how productivity might be increased.

After making his report in December 1866, Muir began implementing many of his time-saving suggestions throughout the factory. But after one of his eyes was injured in an industrial accident, Muir decided that he would not devote his life to mechanical inventions but rather that he would pursue the study of nature.

In April 1867, he resigned from his job and, in June, returned to Wisconsin. In August, he began his famous thousand-mile walk to the Gulf of Mexico, settling in California the next year. Muir devoted the remainder of Muir’s life to the study of nature and the preservation of natural resources. In 1889, he began his campaign for Yosemite, which had been protected since 1864, to become a national park and was instrumental in getting the Yosemite National Park bill passed by Congress. In 1892, he founded the Sierra Club, and, in 1908, Muir Woods National Monument north of San Francisco was created in his honor.

For generations, Muir’s reputation remained untarnished as the “patron saint of the American wilderness” and “father of the national parks.” In recent years, a number of social media posts, blogs, and articles in popular magazines have asserted that John Muir was a racist, claiming that he disparaged Native Americans. In response, Muir scholars have defended him, demonstrating that he expressed dismay for the removal of Indigenous Peoples from their ancestral lands and that his writings reflect a concern about how the Native tribes in California had been defiled and degraded, by white culture, beginning with the Spanish and Mexicans, even before American white settlers arrived.

Muir spoke about “the brotherhood of all peoples of whatever color or name.” In 1872, he wrote a letter to Indianapolis author and teacher expressing his ideals regarding the equality of mankind: “We all flow from one fountain Soul. All are expressions of one Love, God does not appear and flow out, only from narrow chinks and round bored wells here and there in favored races and places, but He flows in grand undivided currents, shoreless and boundless over creeds and forms and all kinds of civilizations and peoples and beasts, saturating all and fountainizing all.” Later in his life, when Muir met Alaska Natives who still had relatively intact societies, he was full of praise for their way of life stating, “They are better behaved than white men, not half so greedy, shameless or dishonest. . . . These people interest me greatly, and it is worth coming far to know them.”

His concern for Native Americans also led him to provide financial support to the Sequoyah League, which was founded by his friend Charles Lummis, a great advocate of Indigenous Peoples throughout the Southwest. The organization helped displaced Native Americans to find new homes and advocated for protecting their religious practices. The Sequoyah League dedicated itself to protecting American Indian rights, opposing the federal policy that permitted the federal Bureau of Indiana Affairs officials to remove their children from reservations and send them to far-away boarding schools. When donating to the Sequoyahj League, Muir wrote, in 1902, “I feel sure that now something sensible and brotherly, will be done for them.”

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.