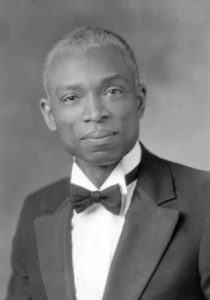

(June 25, 1889-Jan. 28-1998). John Morton-Finney was one of seven children born to George and Mattie M. Gordon Morton-Finney in Uniontown, Kentucky. While his mother was born free, his father was a former enslaved person who traced his family to ancestors who migrated from Ethiopia to the area that became Nigeria. Morton-Finney attributed a lifelong love for learning to his parents, who taught him the value of education.

After his mother’s death in 1903, he and his siblings went to live with their grandfather on a farm in Missouri. Here, Morton-Finney walked 12 miles round trip to school every day. Later, he enrolled at Lincoln College in Jefferson City, Missouri, but interrupted his studies to enlist in the U.S. Army in 1911.

From 1911 to 1913, Morton-Finney served in the Philippines in post-Philippine-American War conflicts as a member of the racially segregated 24th U.S. Infantry, a regiment of the Buffalo Soldiers. Established in 1866 to protect U.S. expansion in the west, these African American regiments went on to serve in the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War, and World War I. Morton-Finney was promoted to the rank of corporal and sergeant but was denied an officer’s commission due to racial discrimination. He received an honorable discharge and came back to the U.S. in 1914.

Morton-Finney returned to Lincoln College in 1914 and earned bachelor’s degrees in math, French, and history in 1916. He then began teaching in a one-room schoolhouse in Jefferson City. In 1918, World War I military service interrupted his continuing studies. For this stint in the U.S. Army, he served as an infantry soldier in France. President Woodrow Wilson’s discriminatory policies led to the Black regiments’ exclusion from the American Expeditionary Force. Instead, the regiment came under French command for the duration of the war—the first time American troops had ever been put under the command of a foreign power.

Upon his return to the U.S., Morton-Finney restarted his education at Lincoln College. During this time, he met his future wife Pauline Angeline Ray, who was a graduate of Cornell University and a French teacher. Morton-Finney enrolled in Ray’s French class and gained her attention.

After earning his first BA from Lincoln College in 1920, Morton-Finney began to teach languages in Black colleges, including Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. He then went on to receive an undergraduate degree from Iowa State University in 1922. That same year, he married Ray. The newlyweds moved to Indianapolis so that Morton-Finney could take advantage of opportunities that the system offered. They had one daughter in 1924.

Morton-Finney taught junior high school mathematics and social studies at IPS Number 27 and Number 17, where he also served as principal. He taught for a brief time at but moved to the new, segregated as one of the original faculty members in 1927. He taught Latin, Greek, German, Spanish, and French, all languages he spoke fluently.

More than an educator, Morton-Finney embraced his role as a counselor of life skills. He taught his students how to set goals, plan for their futures, and take responsibility for their actions. Morton-Finney leaned on his life experience to teach students a deep respect for their heritage and culture. Leveraging his contacts at Black colleges, he invited presidents of these institutions to speak at Attucks. Through his network, he secured scholarships for some of the school’s students to attend college. In all, Morton-Finney’s career spanned 47 years as a teacher, foreign language department head, and administrator.

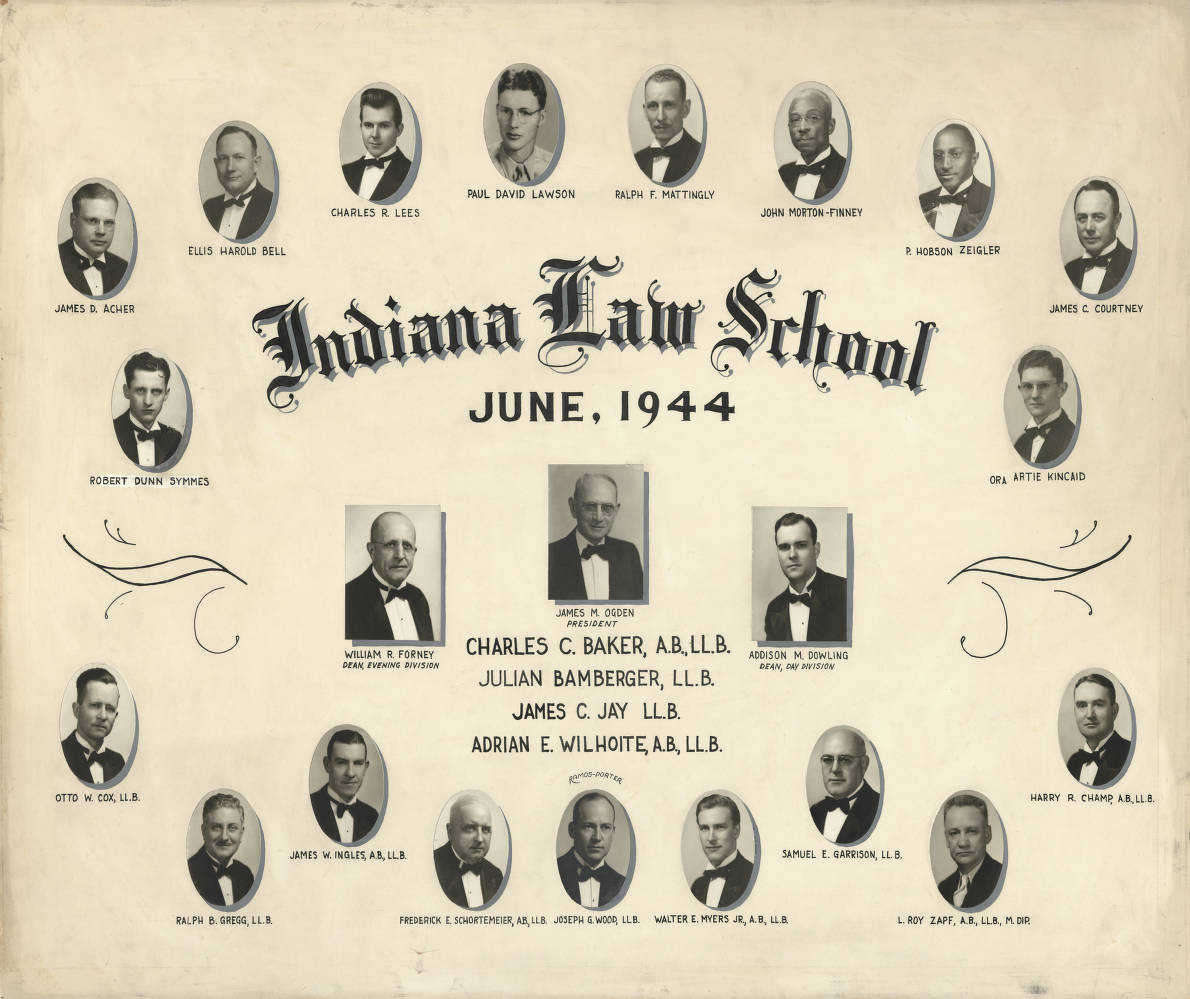

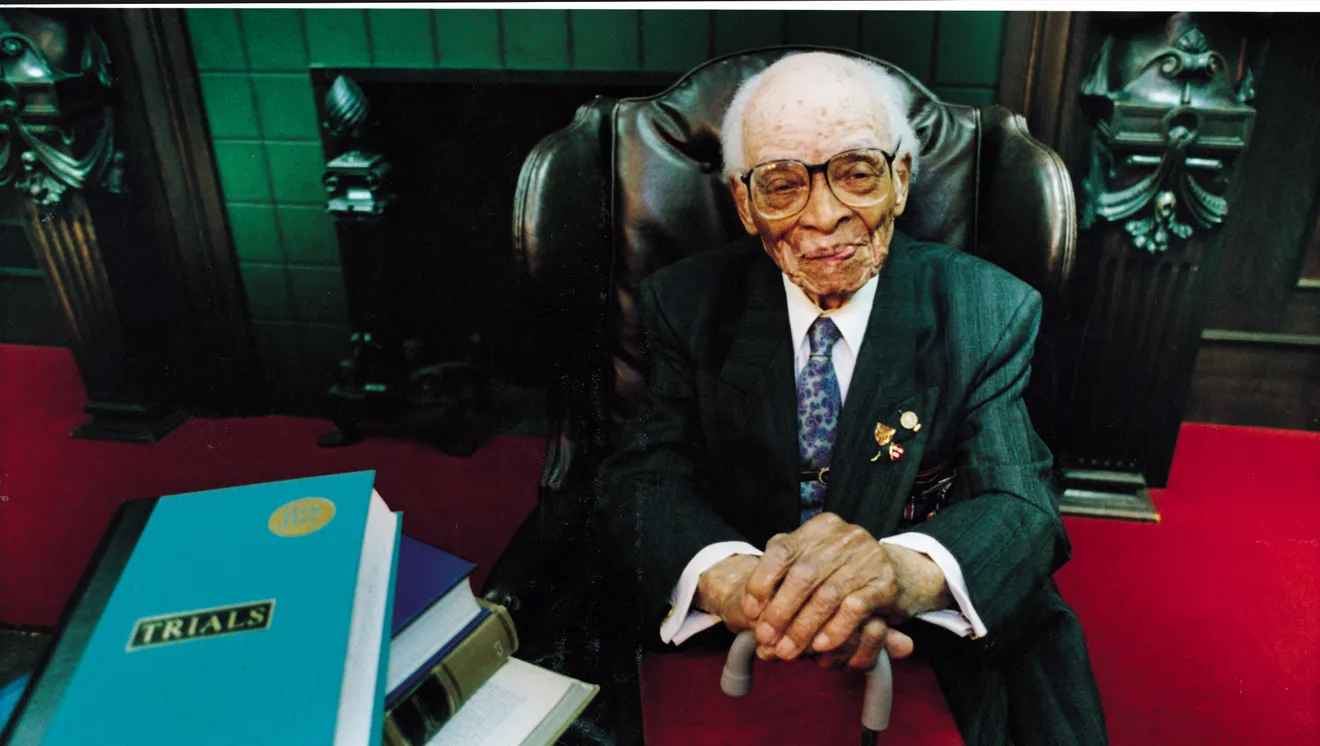

His own pursuit of education did not stop with his second BA from Iowa State University. He earned a third undergraduate degree from Butler University in 1965. Beyond the undergraduate level, he received master’s degrees from Indiana University (IU) in education (1925) and in French (1933); and law degrees from Lincoln College (1935), Indiana Law School (1944), IU School of Law (1946), and Martin University (1995). Lincoln University awarded him a Doctor of Letters (LittD) in 1985, and Butler University gave him an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters (LHD) in 1989. By the time he was done, he had earned 11 academic degrees.

In addition to being an educator, Morton-Finney practiced law. He was admitted as a member of the Bar of the Indiana State Supreme Court in 1935, as a member of the Bar of the U.S. District Court in 1941, and to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1972. For one of his most notable cases, in 1971, Morton-Finney challenged the Indianapolis Board of School Commissioners’ mandatory retirement age of 66. He was 82 years old at the time.

Morton-Finney received a multitude of honors during his lifetime. During World War II, General John J. Pershing cited Morton-Finney’s work in the rationing tickets program for African Americans in Indianapolis. Morton-Finney ensured that strict rationing of scarce consumer items still landed within reach of the African American community.

Proud of his African heritage, he was crowned Adeniran I, Paramount Chief of Yoruba Descendants in Indiana during a ceremony at the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis on August 31, 1979. In 1989, Butler University began presenting an award in his honor to students who demonstrate leadership in the promotion of “diversity and inclusion in their schools or communities.” In 1990, President George H. W. Bush honored him at a White House ceremony, stating he had “lived the life of the mind—better and longer than anyone else” and calling him “America’s most seasoned scholar.” In 1991, Indiana governor Evan Bayh awarded him a Sagamore of the Wabash, and the National Bar Association inducted him into its hall of fame.

Morton-Finney finally retired from practicing law on his birthday, June 25, 1996, when he was 107 years old. At the time of his death, he was the last surviving member of the Buffalo soldiers and the oldest veteran in the state of Indiana. He was buried with full military honors at Crown Hill Cemetery. In 1998, the Indianapolis Bar Association established an award in his memory to recognize local lawyers for outstanding service in leadership education. In 2000, the IPS Board of Commissioners voted to rename its administrative headquarters the Dr. John Morton-Finney Center for Educational Services to honor his nearly five decades of service to the school system, and in 2003, the IU Board of Trustees approved a residential house on the campus of IUPUI to honor him.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.