Individuals of Irish ancestry were among the earliest settlers in Indiana’s capital. Emigrants from Ireland came via eastern cities to central Indiana in response to increased employment opportunities. As early as 1832, the advertised the need for “canal hands” to work on the Wabash and Erie Canal near Fort Wayne. Canal company agents in the East specifically recruited Irish immigrants with inducements of “$10 per month for sober and industrious men” ($302.65 per month in 2020) and Indiana land at favorable rates.

Following the General Assembly’s passage of the overly ambitious Mammoth Internal Improvements Bill (1836), contractors hired Irish workers for massive road and canal construction projects. While many Irishmen settled near their work in small towns like Peru and Logansport, where they quickly developed a reputation for hard drinking and brawling, others moved to Indianapolis to dig the and build the . With the Panic of 1837 and the subsequent end to the public works projects, Irish workers found themselves unemployed within a community unable to absorb them financially.

As their numbers in Indianapolis increased, the Irish began to establish a distinct community. Irish Catholics first assembled for Mass in a West Washington Street tavern around 1837 and later helped found Holy Cross Catholic Church in 1840 (known as after 1850). By the early 1840s, Irish clustered in the same poor area of Indianapolis as African Americans—an area straddling Washington Street and bounded by the and —which indicated the groups’ similar low status.

Facing a growing Irish presence, Indianapolis residents became more aware of events in Ireland, particularly the great potato famine of the late 1840s. In February 1847, some 30 residents met to begin a relief effort for those affected by the blight that was sweeping Europe. Attorney , elected treasurer of the group, noted that there was “n[o]t as much interest as the starving condition of the country requires.” By April, he reported greater success in raising monies and relief supplies, including socks and corn.

In the years preceding the Civil War, the Irish, who comprised the second-largest immigrant group in Indiana, became a more visible and vocal part of Indianapolis. Irish contractors filled the town streets in May 1845, when jobs became available for work on the Indianapolis to Edinburgh railroad. Street skirmishes between the Irish and other groups also became more prevalent. In April 1852, newly naturalized Irishmen and rallied at the county courthouse to oppose temperance legislation. Their increased visibility led to the emergence of “Know-Nothings,” a nativistic organization suspicious of political activities by foreigners.

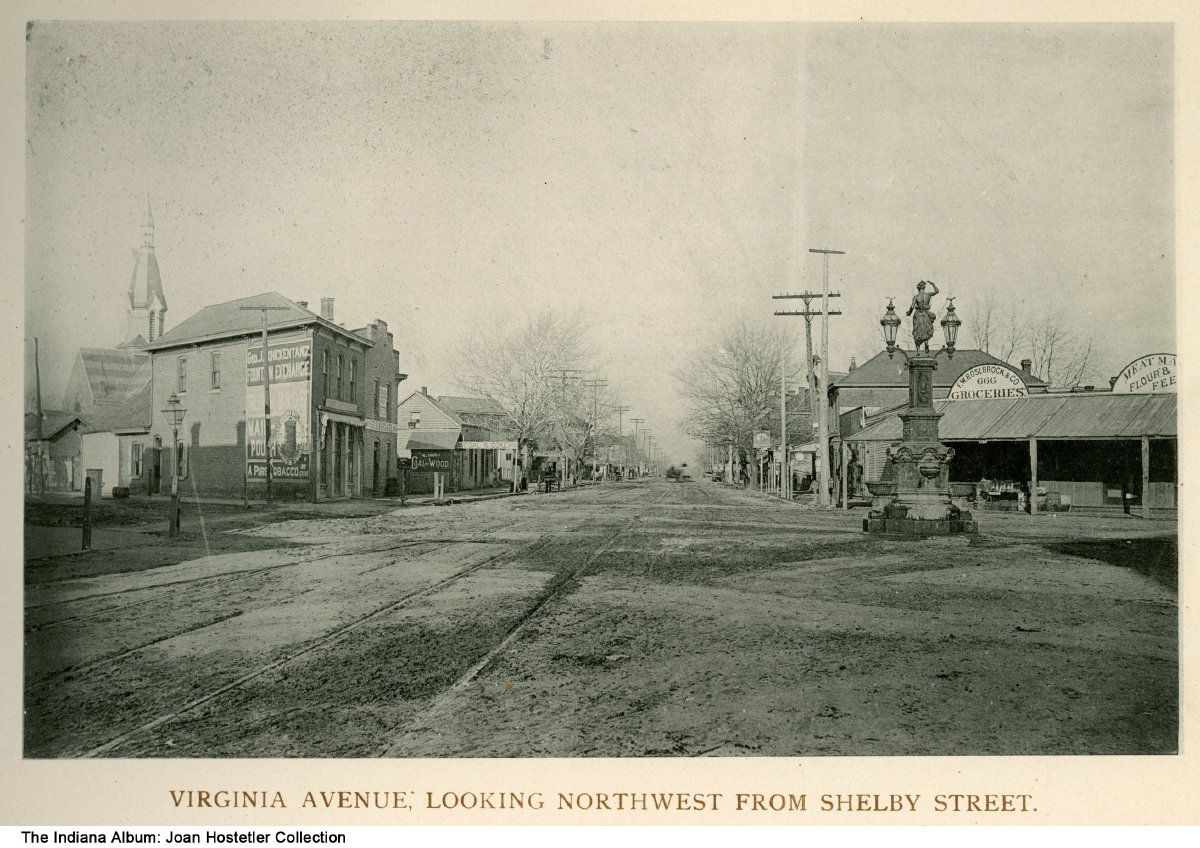

By the early 1860s, the Irish primarily resided in two sections of town. A nine-block area known as , bounded north and south by railroad tracks and by Dillon (Shelby) and Noble (College) streets on the east and west, attracted numerous Irish working-class families and saloons, which earned it a reputation as being the tough part of town.

The neighborhood, located at the end of the Virginia Avenue streetcar line, also attracted the Irish where they established St. Patrick’s Catholic Church in 1865. Residents of these neighborhoods found work in the railroad yards, on construction jobs, or at , an Ireland-based pork packing company, which opened a facility on Maryland Street near White River in 1863 and employed local and imported Irishmen. Women needing employment found work in factories like or Clune Mattress or as domestics in private homes.

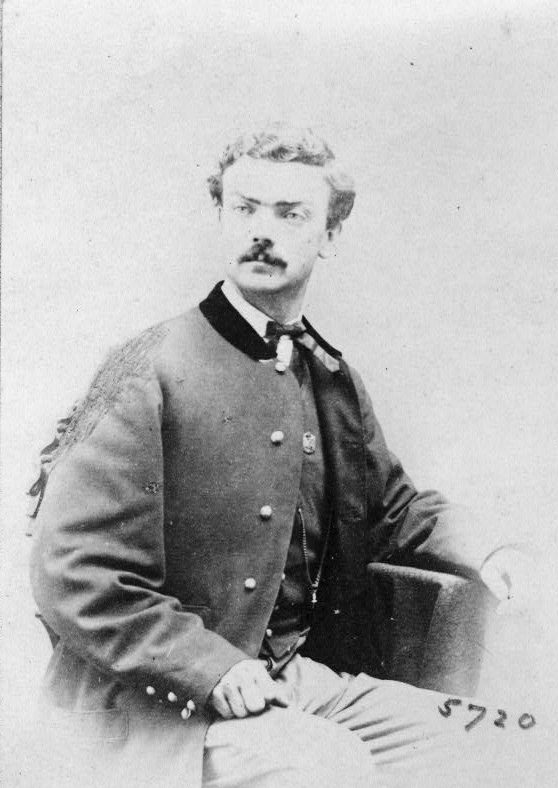

With the coming of the , the Irish quickly responded to the call for volunteers. They raised an Irish regiment (the 35th), commanded by Colonel John Walker of La Porte, and used St. John’s parish school, located at 124 West Georgia St., as a recruiting station. The regiment was later consolidated with the 61st or Second Irish Regiment. Members of the Irish Republican (or Fenian) Brotherhood, a national organization founded in 1857 and dedicated to a free Ireland, saw the war as an opportunity for Irishmen to gain military experience for their forthcoming confrontation with Great Britain.

Immediately following the war, local Irishmen joined in the Fenians’ efforts to seize Canada from Britain and win freedom for Ireland. One of two rival Fenian lodges in the city subscribed money to the abortive effort and equipped 150 men under the command of Captain James Haggerty. Marching in May 1866, the unit joined with other groups to invade Canada from Buffalo, New York. On June 6, President Andrew Johnson ordered an end to the “unlawful proceedings” and the arrest of all offenders.

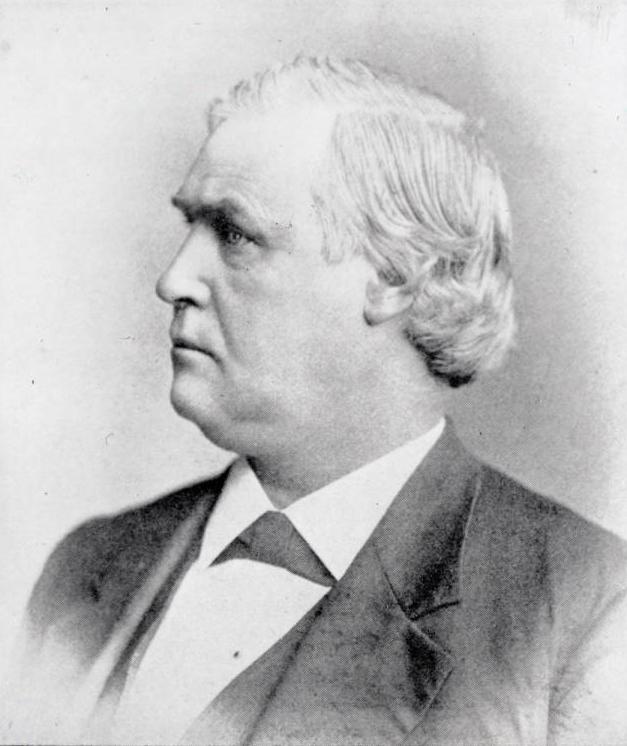

During the 1860s, the Irish became more active in local politics. Primarily Democratic in their political orientation, the Irish generally opposed the for its temperance and pro-business and anti-labor stances. Two of the first Irish-American political leaders in Indianapolis were Republicans— and . Both elected as mayor, Caven served 1863-1867 and 1875-1881, while Macauley served 1867-1873. Their elections showed the emerging political influence of the Irish. Over 3,300 foreign-born Irish resided in Indianapolis (3,760 in Marion County) in 1870, comprising 31 percent of the city’s foreign-born population.

Following ratification of the 15th Amendment, which guaranteed African Americans the right to vote, Indianapolis residents encountered mounting ethnic conflict at the local level. During the 1875 city election, the Democrats’ anti-Black sentiments were countered with vicious anti-Irish attacks in the Republican-oriented Indiana Journal. On election eve, the Journal accused the Democrats of importing Irishmen to vote for the party, and lashed out against the “Irish tramps,” “Hibernian heifers,” and “Romanish herds.”

Quickly, African Americans and the Irish became political rivals. The next year, on May 3, 1876, a special election for city councilmen, clouded by Republican accusations of Democratic gerrymandering, revealed the underlying political and ethnic tensions in Indianapolis. After hearing reports of Democrats intimidating would-be African American voters in heavily Irish Democratic Ward 6 (bounded by Old Madison Street to the east, Raymond Street to the south, Senate Avenue to the west, and Washington Street to the north), nearly 100 African American residents of Ward 4 (bounded by West Street and Senate Avenue to the east, Washington Street to the south, White River to the west, and 10th Street to the north) marched south into the Irish stronghold.

Upon reaching the near and South Illinois Street, the marchers seized hickory sticks from the factory yard and confronted the Irish Democrats. Following an exchange of gunfire and the intervention by police and Mayor Caven, the crowds were dispersed, leaving several African Americans injured, one of whom later died. Despite the labor unrest of the period, this election incident stood out as the city’s worst riot.

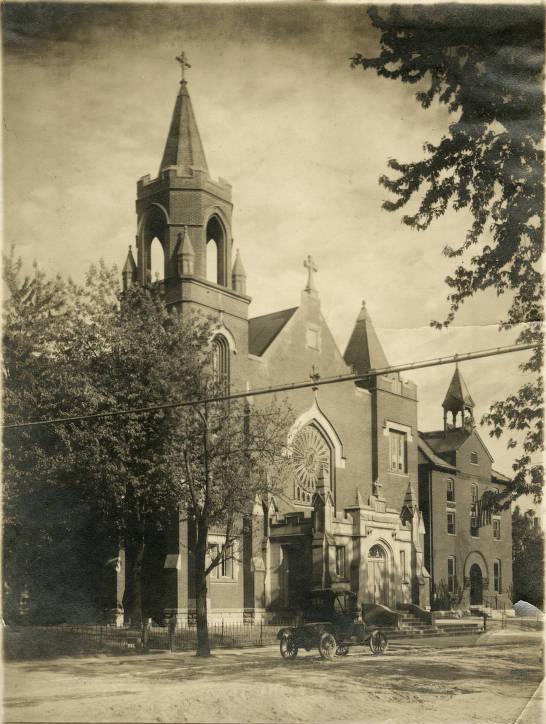

The Irish, who were predominantly Catholic, made the church with its parish societies, special events, and religious celebrations the center of their social life (See ). Several parishes opened over the years to serve the increasing numbers of Irish families—St. Peter’s (1864-1865, renamed St. Patrick’s, 1870); St. Joseph’s (1873); St. Bridget’s (1880); St. Francis de Sales (1881); and St. Anthony (1891). Likewise, an Irish Catholic school located on Tennessee (Capitol Avenue) between Maryland and Georgia streets served the local children. In 1879, an Irish Delegate Assembly held in Indianapolis attracted representatives from Irish societies and churches statewide. Following a St. Patrick’s Day parade, they heard Bishop speak on “The Social Mission of the Irish Race.”

Irish associational life was centered in Ward 6, clustering in the vicinity of St. John’s church. The , a local chapter of the secret society devoted to mutual assistance and Irish independence, formed in 1870 and flourished locally despite opposition from Bishop Chatard. By 1910, it maintained eight divisions with 1,000 male members and nine female auxiliaries with 1,100 members.

In subsequent years, the Hibernians protested the intolerance of the in the 1920s and sponsored an annual St. Patrick’s Day parade that was discontinued in 1932. Other organizations included the Emerald Beneficial Association, the Knights of Father Matthew, St. Augustine Ladies’ Total Abstinence Society, and the United Irish Society. The first local council of the Knights of Columbus was established in June 1899.

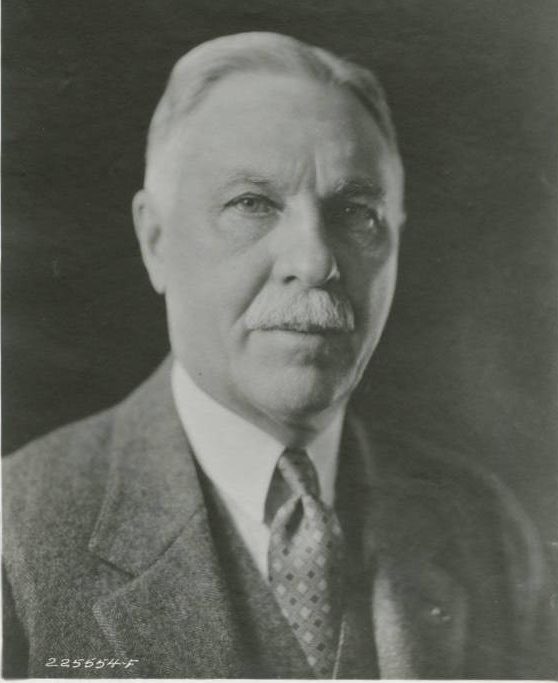

One of the most influential Irishmen in Indianapolis was Democratic politician . Born in County Monaghan, Ireland, Taggart worked his way up through the political ranks to head the local and state . He was elected mayor in 1895, 1897, and 1899, became chairman of the Democratic National Committee in 1904, and was appointed to fill a vacancy in the U.S. Senate in 1916.

By 1910, the Irish were the second-largest ethnic group in the city, numbering approximately 12,225 (3,255 foreign-born, 8,970 native-born of foreign parents), and comprising 5 percent of the total population and 15 percent of the foreign population. This group, while affirming its loyalty to the United States during , generally supported the local German community and the German cause out of antagonism toward Britain. One of the most pro-German journals in the state was Joseph Patrick O’Mahony’s ( by 1916), which carried anti-British editorials. In 1915, the Irish rallied with Germans in several Hoosier cities to protest America’s partiality toward the Allies.

While the Irish had resided primarily on the near east, south, and west sides of the city, by 1920 there was considerable movement out of the downtown neighborhoods of St. John’s and St. Bridget’s. Irish-born residents, who numbered 2,414 or 33 percent of the state’s Irish-born population, established new enclaves on the eastside around Holy Cross Parish (Oriental and Ohio streets, 1895), St. Philip Neri Church (North Rural Street, 1909), and St. Therese (Little Flower) Parish (established 1926).

The ensuing decades witnessed declining immigration of Irish to Indianapolis, although individuals of Irish ancestry still comprised the second largest ethnic group in the city. Catholic parishes continued to attract the Irish to the surrounding neighborhoods but increased evidence of Irish assimilation reduced their distinctive presence of earlier years.

In 1970, there were 2,752 persons of Irish stock (427 Irish-born, 2,325 native-born of foreign parents) in the city, placing the Irish fourth behind Germans, , and . Among Marion County’s residents in 1980, over 18 percent (138,407 individuals) reported Irish ancestry. As of 2018, 221,000 Indianapolis residents (11.2 percent) reported Irish ancestry.

Since the founding of Indianapolis numerous individuals of Irish ancestry have played leading roles on the local scene, including pioneer ; Mayors John Caven, Daniel Macauley, , , , , and ; police chief ; and bankers and politicians and . Kerry J. Forestal was elected Marion County Sheriff in 2018.

In 1980, the revived the St. Patrick’s Day Parade, which had been dormant since the 1920s. The parade and its activities have flourished and expanded. Events in the celebration include greening of the canal by the Irish citizen of the year, the mayor and the governor; an annual parade; and the Shamrock Run and Walk.

In September 1996, the Irish community held its first “Irish Fest” – a one-day event held at the . The annual event has flourished and has expanded to three days at . Irish Fest spawned the Irish cultural foundation of Indianapolis to support traditional Irish culture.

To commemorate the contributions of the Irish to Indiana and Indianapolis, the Irish American Heritage Society and the Ancient Order of Hibernians on March 17, 1990, dedicated a Celtic limestone cross in the churchyard of St. John Catholic Church. The inscription reads: “In memory of the faith and determination of the Irish people who settled in Indiana, we dedicate this Celtic Cross to challenge Irish Americans to keep that faith and determination and to build a better tomorrow.”

In 2001, the Kevin Barry Division Ancient Order of Hibernians dedicated a monument to the first Civil War Irish Regiment of Indiana, the 35th Volunteer Infantry. The memorial, reminiscent of an ancient Irish Dolmen of two stones, reads: “1st Irish of Indiana 35th Volunteer Infantry.” “In faithful remembrance of the sacrifices by sons of Erin in the War for the Union 1861 – 1865).”

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.