Previously known as the Holy Cross Westminster neighborhood, in 2020 the area known as Holy Cross lies on Indianapolis’ near east side, bounded by Michigan Street, State Street, Southeastern Avenue, and Davidson Street. The neighborhood takes its name from the Holy Cross Catholic Church and School.

Holy Cross is part of several near eastside neighborhoods whose history began as early as 1819 when early settler built a cabin on the bank of a creek that later bore his name, Creek. In 1822 Casey Ann Pogue received a land patent from the federal government for a tract of land along New York Street, between Oriental and Highland streets.

A decade later, Governor Noah Noble purchased Pogue’s land tract where he built his family home, Liberty Hall on Market Street. Though Noble and his wife had 14 children, only 2 survived to adulthood. Daughter Catherine Noble married Alexander H. Davidson in 1840, and upon Noble’s death in 1844, the Davidsons inherited 80 acres of land upon which they built their home Highland House. Four generations of Davidson’s lived here.

At this point the history of the near eastside neighborhoods took shape. In 1849 the heirs of Governor Noble platted a subdivision in the farmland of the former governor. Bounded by St. Clair, Market, and Pine streets, and Noble (College) Avenue, the subdivision included 135 lots.

The near eastside continued to develop in 1863 when the federal government purchased 76 acres of land to erect a . The Citizen’s Street Railway Company established streetcar service outside the that spurred the movement of residents and the development of housing closer to the Arsenal.

That same year allowed for growth in the southwest corner of the subdivision in an area called . By 1866 streetcars passed over Pogue’s Run. The city of Indianapolis purchased hundreds of acres of land from attorney to establish Brookside Park in 1870. A few years later in 1872, president James O. Woodruff platted , which became an incorporated town in 1876. Streetcars allowed for these neighborhoods to organize. With the completion of the Belt Line Railroad between 1877 and 1878, industry and laborers pushed deeper into the Highland-Brookside neighborhood to establish a new area called Cottage Home.

By the 1880s many of the city’s immigrants had settled along the area’s western edges near . To meet the needs of these Irish Catholics, as well as the growing number of Italian and German , the Catholic diocese founded the Holy Cross Church to minister to these immigrants.

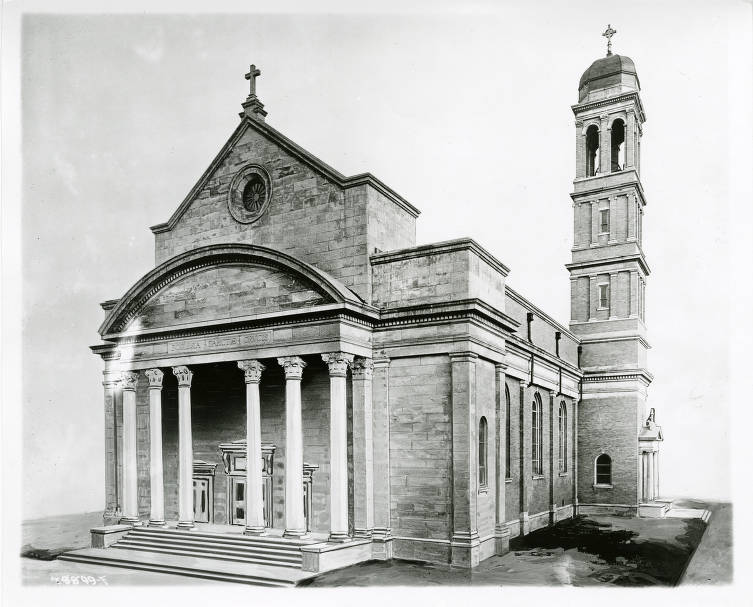

In April 1886 the diocese laid the cornerstone for the Holy Cross Roman Catholic Church (125 North Oriental Avenue), which was dedicated on August 8, 1896. The initial congregation of 300 increased to 900 before the church’s first anniversary. The Holy Cross Catholic School opened sometime between 1900 and 1905. Westminster United Presbyterian Church, at 445 North State Avenue, shared a border with the neighborhood.

In 1898 the last generation of Davidsons sold the family home to the City of Indianapolis with the stipulation that the home be demolished to make way for a park. Highland Park became the centerpiece of the Holy Cross neighborhood.

As the number of Holy Cross parish congregants increased the church began collecting funds in 1912 for the construction of a larger facility. This took almost nine years, but in 1921 construction started at Oriental and Ohio streets, with a dedication ceremony on July 2, 1922.

The surrounding community saw continuous growth in both residential and business development until 1940. After 1940 residents and then businesses began to move out of the neighborhood to the suburbs, leaving behind empty decaying structures. During the 1960s many middle-class families moved to the suburbs, taking their churches with them. However, Holy Cross Catholic Church remained and increased community outreach programs during this transitional period to meet the needs of its changing neighborhood. Further population decline followed the demolition of homes for the construction of the I-65/I-70 loop in the early 1970s.

In 1970 Father James Byrne of Holy Cross Catholic Church founded the (NESCO), an umbrella organization, to address the community’s decline through projects like the Near Eastside Multi-Service Center. The center offered social services to neighborhood residents. Publicity around the successful nomination of neighboring Woodruff Place on the National Register of Historic Places failed to provide the impetus needed to spur population growth in near eastside neighborhoods.

In fact, by 1975 Holy Cross Catholic Church witnessed its lowest membership in the church’s history. In 1977 the establishment of Eastside Community Investments (ECI) with Father Byrne as its first president aimed to reverse the population decline through business development and revitalization of housing. These efforts paid off after the city of Indianapolis designated the near eastside as a Community Development Grant Target Area, a designation that provided the area with funds for infrastructure improvements.

However, in the late 1980s nearly half of the 929 homes in the Holy Cross area were rental properties. Many of these deteriorating two-story early 20th-century frame structures suffered from lack of maintenance. In 1998 newly founded Re-Development Group (Re-Dev) focused on renewing downtown communities, starting with Holy Cross. As a result, rehabilitation of dilapidated homes and construction of new ones on nearly every block spurred a resurgence in the area.

The Highland 14 project on Highland Avenue across from witnessed the greatest impact of the revitalization effort. Here, single-family homes replaced an abandoned church, an unkempt house, and an abandoned warehouse. The neighborhood architecture bore a mixture of styles ranging from modern approaches to the maintenance of the historic styles of the original homes. This approach aimed at uniting the commercial western side of the area with the residential eastern side. This period of revitalization also brought businesses back to the neighborhood.

When moved into Holy Cross in 2000 the neighborhood embarked on a period of focused revitalization. Holy Cross turned the rental properties from the 1990s into stylish owner-occupied homes, while Angies’s List kept the historic exterior façade to its company building.

In 2005 broke off from Holy Cross. By 2012, Holy Cross had become a strong and active community with nearly 80 neighbors attending quarterly meetings. In 2014, Arsenal Heights merged with Holy Cross to become a single neighborhood, and the Holy Cross Neighborhood Association adopted the street just west of I-65/I-70 (Davidson Street) to symbolize its opposition to allowing the Interstate highway to divide Holy Cross from downtown.

The same year, in November 2014 the Catholic Archdiocese of Indianapolis closed Holy Cross Catholic Church. Four years after the building’s arched portico collapsed in 2015, the church was added to the 10 Most Endangered List. In 2019 the stained-glass windows of the church were removed and sold to a church in southern Indiana.

In 2018 Angie’s List departed its Holy Cross location and leased the building to Ball State University’s Indianapolis location of its College of Architecture and Planning, known as the CAP. After the arrival of CAP, Holy Cross continued to add a variety of small businesses, including a daycare for dogs, an antique mall, an artisanal meat producer, breweries, restaurants, retailers selling house plants to paper goods, and a garden service.

The elimination of abandoned properties and focus on owner-occupied homes rather than rentals continues as Holy Cross charts its future. The Holy Cross Neighborhood Association aims at developing and establishing a cultural presence with projects like traffic-signal-box art, art installations, building and bridge murals, the Latino Welder’s Guild Esplanade Sculpture, and the Mary Miss Streamlines sculpture. Community engagement remains strong as the neighborhood association works toward residential, cultural, and economic stabilization.

Is this your community?

Do you have photos or stories?

Contribute to this page by emailing us your suggestions.