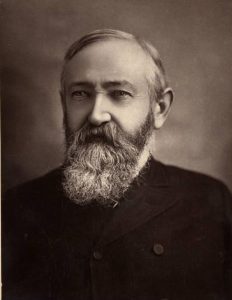

Photo info …

Credit: Indiana Historical SocietyView Source

(Aug. 20, 1833-Mar. 13, 1901). Born in North Bend, Ohio, Benjamin Harrison was the grandson of President William Henry Harrison. He came from a long line of Harrisons named Benjamin, who had been prominent in the development of colonial Virginia. The best-known was his great-grandfather Benjamin Harrison V, a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

The son of Elizabeth Irwin and John Scott Harrison, he grew up on a 600-acre North Bend, Ohio farm called The Point, which had belonged to his grandfather. Harrison attended Farmers’ College in Cincinnati, where he met Caroline Lavinia Scott, the daughter of one of his professors. Scott’s father moved to Oxford, Ohio, and Harrison followed. In Oxford, he attended and graduated from Miami University. Harrison married Scott in October 1853. The couple had their first child, Russell, 10 months later in April 1854. The couple also had one daughter—Mary Harrison McKee.

After reading law in Cincinnati, Harrison was admitted to the bar in 1854 and moved to Indianapolis. He later stated that he left Cincinnati “to cut his leading strings and acquire an identity of [his] own.” When he visited Indianapolis, he received a warm reception with the remembrance of his grandfather. A cousin, William Harrison Sheets, who had moved to Indianapolis when he was elected Indiana Secretary of State in 1832, also encouraged Harrison to move to the city, citing its business advantages. In Indianapolis, he steadily advanced in the legal profession. A committed Christian, he became an elder in the First Presbyterian Church at age 28.

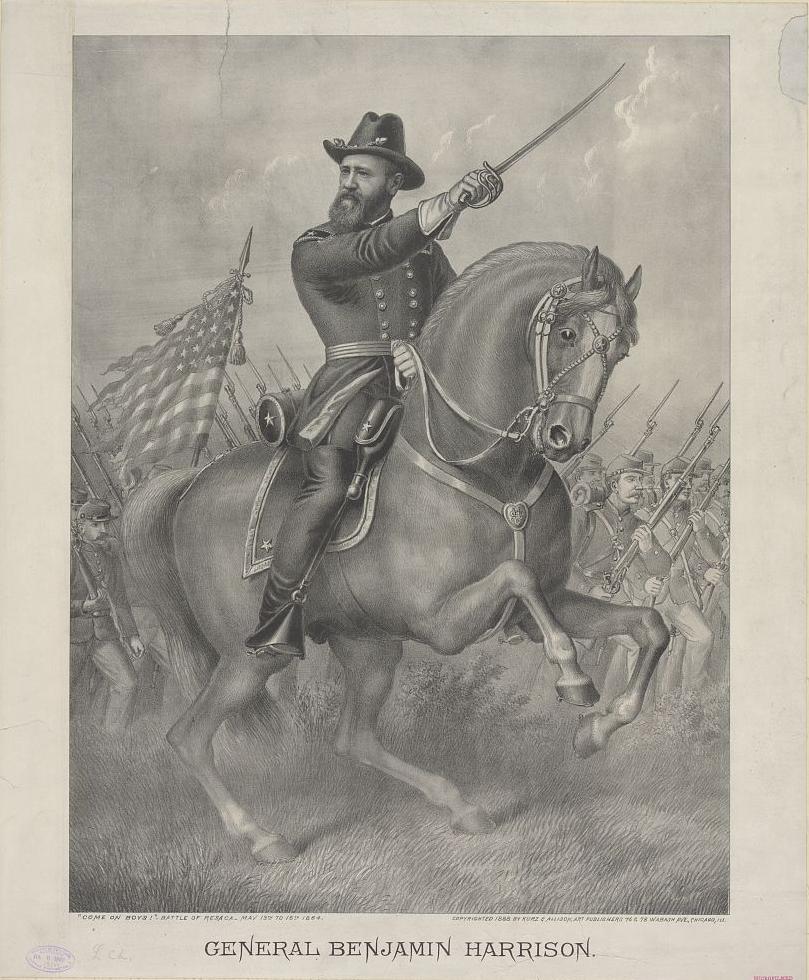

With the Whig party’s demise, Harrison took an active part in Indiana Republican politics. He served as city attorney in 1857 and three years later was elected reporter of the state Supreme Court. He left the post in 1862 when Governor asked him to raise a regiment, the 70th Indiana Infantry, and commissioned him as a colonel for the . Serving in the Army of the Cumberland, Harrison emerged with the rank of brevet brigadier general.

In 1865, Harrison returned to Indianapolis and the job of Supreme Court reporter, which he had regained in the previous year’s election. Upon completing his term, he turned to full-time private practice. By 1875, his great success allowed him to build a large new residence on North Delaware Street (See ).

Courtroom triumphs, addresses before veterans’ groups, and effective stump-speaking brought him increased political prominence, and he moved steadily up through the ranks in the . In 1876, when the party’s gubernatorial nominee Godlove S. Orth retired from the race amid allegations of financial misdealing, Harrison stepped into the breach and waged a gallant, though losing campaign to Democrat James D. Williams, nicknamed “Blue Jeans Bill,” the only farmer ever elected to the office.

When the great reached Indianapolis in late July, Harrison took command of a citizen militia company to maintain order, but he also argued that the workers had legitimate grievances that ought to be addressed once they returned to work. The incident underscored his reputation as a defender of law and order, but many labor organizations subsequently saw him as an enemy. Even so, his political career flourished. When Oliver P. Morton died in late 1877, Harrison succeeded him as leader of the state’s Republicans. In 1881 he easily won election to the U.S. Senate.

In the Senate, Harrison campaigned for generous pensions of Civil War veterans, supported education for African Americans, and broke with the Republican Party when he voted against the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. He also introduced a bill to preserve land along the Colorado River. Although it did not pass, it laid the groundwork for Grand Canyon National Park to be established in 1919.

In 1888, the Republican Party nominated him for president, and Indianapolis became the focus of the campaign. First at his Delaware Street house and later at , Harrison daily addressed visiting delegations. Reporters recorded his remarks, which appeared in newspapers across the country.

Harrison defeated Grover Cleveland and served as president from 1889 to 1893. Although often considered a mediocre or average president, along with other presidents of the last decades of the 19th century, Harrison’s administration has been reevaluated by historians since the 1960s. He had a reputation for being stiff, but he worked well with a Republican Congress his first two years in office and several pieces of legislation that he supported were landmark bills. He also was productive in foreign affairs.

In 1890, the McKinley Tariff Act passed Congress with Harrison’s backing. The highest protective tariff in U.S. history, it raised rates 49.5 percent, but it also gave unprecedented authority to the president in the area of foreign trade that has continued into the 21st century. The act gave the president the power to hold trade conventions and to negotiate reciprocity agreements with foreign entities without congressional oversight. It also provided for the creation of a federal bureaucracy to administer the functions and details of foreign trade. The act created new executive powers, but the tariff it levied has been cited as a contributing factor to the economic collapse of 1893, which was the most severe depression the country had seen up to that time.

Harrison also supported the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, another piece of legislation passed in 1890 that has had lasting implications. Senator John Sherman of Ohio served as its sponsor. Intended to stop large companies, such as John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust, from creating monopolies that eliminate competition and set rates and prices, it was the first federal law passed to regulate corporate monopolies. Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt later strengthened the Sherman Anti-Trust Act and used it against companies that restrained trade or commerce through “contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy.” The Sherman Anti-Trust Act remains in effect.

In foreign affairs, Harrison is credited with having done more to put the U.S. on a path to a world empire than any other president had previously. He put commercial reciprocities in place and supported the annexation of Hawaii and the creation of an American protectorate in Samoa. He also pushed for the creation of the Panama Canal. In addition, Harrison increased naval expenditures to make the U.S. a legitimate naval power. When he entered office, the U.S. Navy only had two commissioned warships. Seeing a need to make the U.S. more competitive with Great Britain and Germany, Harrison championed a program for the rapid construction of modern warships. With all of these actions, Harrison set an agenda for American foreign policy that would be followed for the next three decades.

Continuing work that he had undertaken in the Senate, Harrison pushed through the enactment of the Dependent and Disability Pension Act, which provided pensions to disabled Civil War veterans. He endorsed congressional legislation to protect the voting rights of African Americans and to grant color-blind funding to public schools. He also proposed a constitutional amendment that would have overturned an 1883 U.S. Supreme Court decision that declared much of the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional. Although Congress failed to approve any of these measures, they laid the groundwork for the future.

During his administration, Native Americans continued to be pushed out of their ancestral lands. Within days after taking office, he signed a proclamation that opened Native American land in Oklahoma to white settlement. Harrison forced the Sioux to give up 11 million acres and the Crowe to give up 1.8 million acres of land in the Dakotas and Montana respectively. In correspondence with these actions, six states entered the Union: North Dakota and South Dakota (1889), Montana (1889), Washington (1889), Idaho (1890), and Wyoming (1890). Relations with the Sioux Nation also brought tragedy under his watch. On December 29, 1890, the U.S. Army massacred 150 Sioux men, women, and children at the Battle of Wounded Knee.

At the same time, Harrison pushed for legislation that provided for the management of western forestland. Following its passage, he used the law to set aside 22 million acres in California, Colorado, New Mexico, Oregon, Washington, Alaska, and Arizona, and to open three national parks—Yosemite, Sequoia, and Kings Canyon. While championing conservation, Harrison disregarded the rights of Native Americans who had been caretakers of the land, and he, along with such conservationists of the era as , envisaged geography that was emptied of indigenous peoples.

In other realms of domestic policy, Harrison’s support of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890 proved to be a misstep. Senator John Sherman again served as sponsor of the act, which he negotiated as a concession to senators in the western states. With the recent addition of western states, they represented a much stronger influence in Congress than ever before. With the Silver Purchase Act, Sherman advocated silver as a monetary standard in return for western support of the McKinley Tariff. Following the stipulations of the Act, U.S. Treasury was required to purchase silver every month at market rates and to issue notes redeemable in gold or silver. With its implementation, the supply of silver increased and drove down prices, and holders of U.S. notes redeemed them in gold, leading to a depletion of gold reserves. The act was a key factor in the 1893 economic depression. Following the financial collapse, Congress repealed it.

Harrison lost an electoral rematch with Cleveland in 1892. Immediately following his term in office, in 1893, Stanford University Law School engaged him to be one of its first law professors. He gave a series of lectures on Constitutional law.

In 1896, Harrison married Mary Scott Lord, the niece of , who had died in the White House in 1892. With Lord, Harrison had one daughter, Elizabeth Harrison Walker. Working at the law, engaging in church work, and making occasional political speeches, he lived his remaining years in Indianapolis and is buried in .

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.