Although much of the U.S. press called for war against Spain following the February 15, 1898, sinking of the USS Maine in Havana harbor, Indianapolis newspapers hesitated to blame Spain for the act. Only the Indianapolis , a weekly, expressed any eagerness for military action. The (one predecessor to the ) initially opposed American intervention in Cuba but later encouraged Catholic youth to prove their loyalty by volunteering for military service.

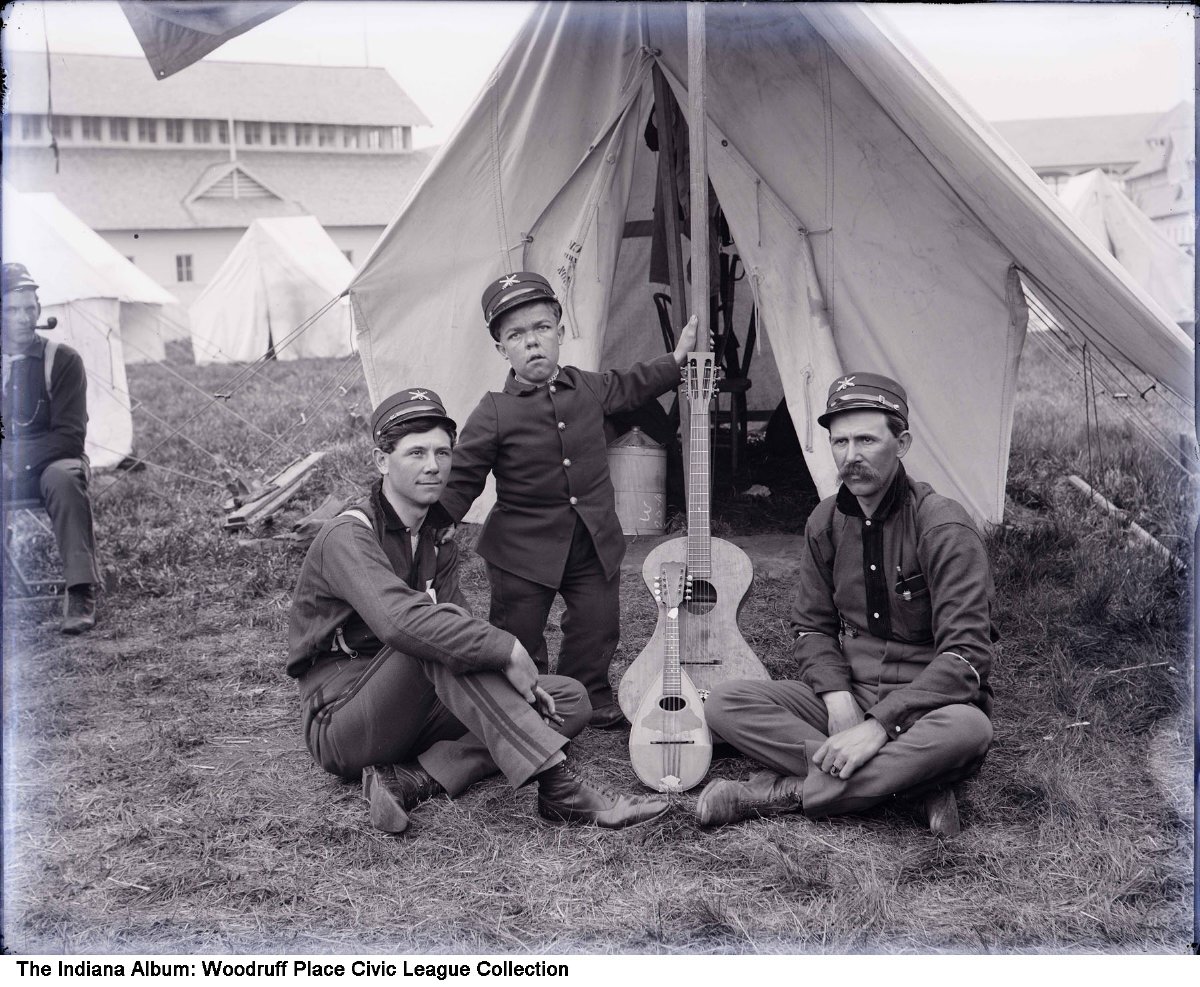

Following the United States’ declaration of war against Spain (April 25, 1898, retroactive to April 21) and Governor James A. Mount’s mobilization of the , about 5,000 men reported to the (designated Camp Mount) in Indianapolis.

By mid-May, three infantry regiments and two artillery batteries mustered into federal service and transferred to Chickamauga Park, Georgia for training. Other units followed in the ensuing weeks. In July, the 161st Regiment Infantry organized in the city under the command of future governor Winfield T. Durbin. It did not leave the state until mid-August and served as an occupying force in Cuba following the war.

Included among the Indiana volunteers were several companies of Indianapolis men—Companies “A,” “D,” and “H” of the 158th Regiment Indiana Infantry; and Battery “A,” 27th Indiana Light Artillery, which was on the firing line in Puerto Rico when peace was declared. Two local companies of African Americans under the command of Captains Jacob M. Porter and John J. Buckner of Indianapolis never saw combat and were dismissed in late October. Other local men rounded out the rosters of Indiana units.

Patriotism in the city was strong throughout the war. Parades and military events were frequent, beginning with the departure of the first regiments in May. Memorial Day (May 30) featured the usual parade in downtown Indianapolis along with speeches and the decoration of graves in the national cemetery at .

On August 11, a crowd estimated at over 12,000 gathered in to watch a reenactment of the Battle of Santiago. Although inefficient transportation slowed their arrival at the event, those attending witnessed a massive military display. Military units returning home later in the year and in 1899 were also greeted by cheering throngs of Indianapolis citizens.

Several of Indianapolis’ more notable citizens volunteered for service during the war, including Russell Harrison (son of former President ), (son of ex-Consul General and publisher ), and (son of , candidate for vice president in 1880). Captain New served on the staff of General Fitzhugh Lee, a nephew of Robert E. Lee who had been appointed consul general Havana by President Grover Cleveland and remained in that position until the outbreak of the war. Captain English was an aide to Major General Joseph Wheeler, who commanded the cavalry division that included Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders. Upon returning home, English founded the National Association of United Spanish War Veterans and served as its first commander-in-chief.

At least one member of the Black 10th U.S. Cavalry, killed in an advance up San Juan Hill, was an Indianapolis native. Will H. White’s sacrifice was highlighted in a local newspaper article published in June 1898. Other local combatants were occasionally featured in the .

In addition to the military presence at Camp Mount, the on the city’s eastside was commissioned to manufacture canvas haversacks for the army and employed over 100 people to accomplish this task. Also, the fairgrounds served as a staging area for volunteers throughout the war. Despite this, the annual State Fair managed to take place as usual in the fall of 1898. The last regiment of volunteers disbanded on May 3, 1899, bringing an end to the city’s participation in the Spanish-American War.

Following the war, Indianapolis remained somewhat divided over the issue of American expansionism. The claimed “it was a misnomer to call our war with Spain a war for humanity.” The Democratic opposed annexation of Hawaii, Puerto Rico, or the Philippines, while Republican papers like the , though unenthusiastic about expansion, eventually accepted annexation as the official party position.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.