Methodists historically have been the largest Protestant group in Indianapolis and Central Indiana. Today, local Methodist churches and agencies provide city residents with a variety of social services in addition to ministering to their spiritual needs. In addition to an extensive network of churches and missions, organized Methodists also founded many major Indianapolis institutions, including and the .

Four different Methodist denominations have churches in Indianapolis: the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, and the United Methodist Church. Together they have over 84 churches and missions in Marion County and approximately 37,500 members in 2010 (the latest year for which local membership statistics were available). In addition, several Indianapolis churches are affiliated with Holiness denominations, which share a Methodist heritage.

Early Years, 1820s-1850s

All Methodist denominations have roots in the work of John Wesley, an 18th-century Anglican reformer. Wesley directed his emotional evangelism primarily at the poor, emphasizing religious experience and moral conduct over doctrinal sophistication and ritual. He preached free will and the obligation to strive for holiness and Christian perfection. The lay organization Wesley set up in England spread to America in the 1760s and became the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1784, after the Revolution made a continued connection with the Church of England impossible. The core of this new church was a tight-knit group of itinerant preachers who maintained an expanding network of preaching circuits projecting far into the frontier.

The Methodist Episcopal Church (M.E.) is the direct forerunner of the present United Methodist Church (U.M.) and was the first Methodist group in Indianapolis. M.E. itinerant preacher William Cravens reached Indianapolis in 1821 and organized a local society or class meeting as part of a central Indiana circuit. Beginning with only seven members, it was the town’s first religious congregation of any kind and provided early residents with a base of social and religious life.

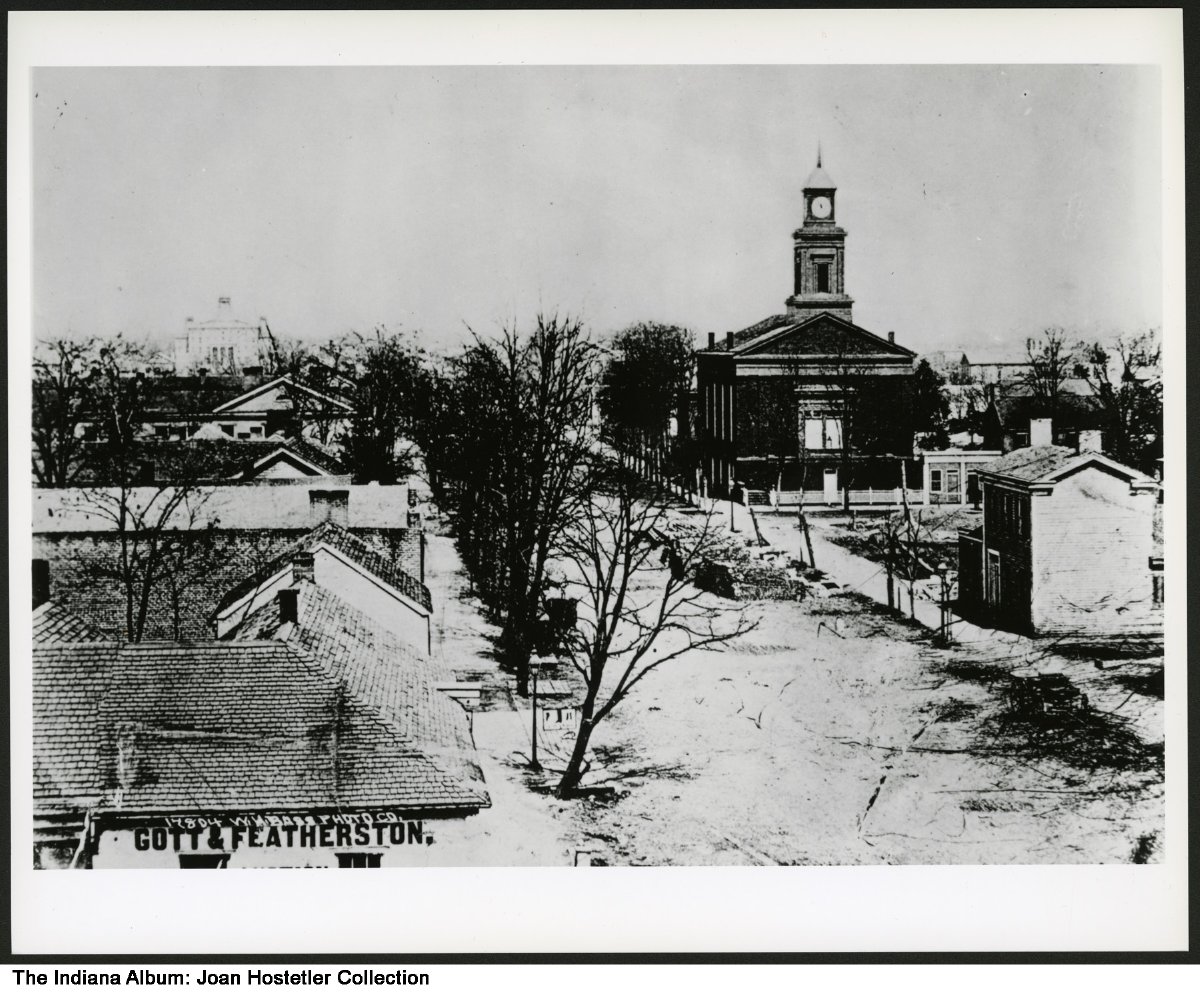

An emphasis on evangelism characterized local Methodism in the early 19th century. Local M.E. clergymen such as John Strange, Alan Wiley, and James Havens won fame as powerful evangelists at frequent camp meetings and other extended revivals that swelled church membership. In 1828, the Indianapolis congregation was taken off the circuit and given its own minister. The next year it built Wesley Chapel, the forerunner of , on the corner of Circle and Meridian streets. In 1830, the denomination underwent a schism when the Methodist Protestant Church split away to set up a more democratic form of church government.

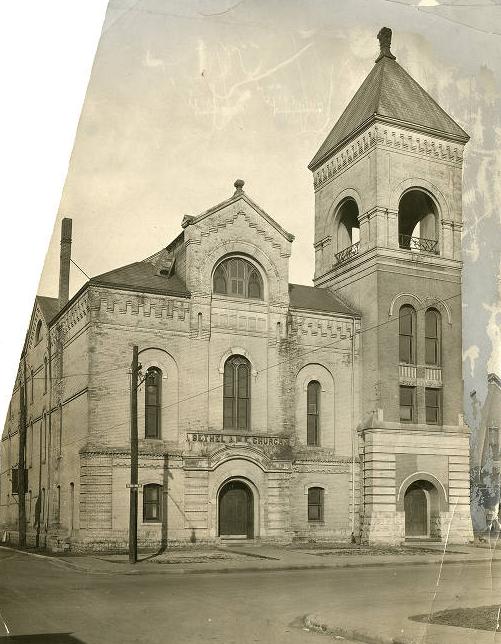

In 1836, , affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) denomination organized in 1816, became the first African American church in Indianapolis. Bethel was founded as a station on the AME Church’s Western Circuit. It quickly became a major focus of community life for Indianapolis Blacks. Prior to the , the church reputedly served as a station on the Underground Railroad.

In 1842, when local membership at Wesley Chapel topped 600, Indianapolis got its second Methodist Episcopal congregation, which erected in 1846 at Pennsylvania and Market streets. More churches and missions quickly followed.

Prosperity, the Rise of Formal Religiosity, and Social Reform, 1860s-1930s

As the Methodist Episcopal Church grew and prospered with Indianapolis, it gradually came to represent the values of the upwardly mobile middle class. By the end of the Civil War, the rough evangelism of frontier Methodism was giving way to a quieter, more formal religiosity. Congregations began to demand an educated clergy, and churches acquired choirs, organs, and stained-glass windows. At the beginning of the 20th century, the city’s Methodists were at the forefront of business, local, state, and national politics, as well as the professions like law and medicine.

Many members dissented and tried to preserve the older traditions, dividing some local congregations between rich and poor, but the more affluent and modernist elements prevailed. Local Methodist growth was offset slightly by defections to other denominations, especially , that attempted to maintain the style of old-fashioned Methodism.

Bethel AME continued to be an important institution for African Americans. Its building burned during the Civil War in July 1862 but was rebuilt at Vermont and Toledo streets. In 1867, the congregation started a school for local Blacks, and in 1869 it opened a new building at 414 West Vermont Street. The area surrounding the church near was then transforming into a thriving Black community. Bethel would remain at this location for nearly 150 years.

In this era, two other Black denominations created in the 19th century in response to racism by white Methodists—the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ) (1821) and the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (CME) (1870)—organized Indianapolis churches. The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church set up Jones Tabernacle, its first Indianapolis congregation, in 1872. The Colored Methodist Episcopal Church, now known as the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, erected Phillips Temple on the near west side in 1906.

To accommodate people outside its mainstream, the M.E. Church created ethnically distinct congregations. Two German-speaking congregations were established in Indianapolis, attached to a German conference organization. In the late 19th century, the denomination segregated Indianapolis African Americans into several all-Black congregations responsible to their own conference organization.

From the 1880s through the 1920s, the M.E. Church devoted much of its energy to reforming society. Indianapolis Methodists espoused causes from public education to Sabbatarianism (strict observance of Sunday as the sabbath) (See ). Above all, they battled against the use of alcoholic beverages and became deeply entwined in the movements. Local Methodist leaders played major roles in most of the large prohibitionist organizations, including the , the Anti-Saloon League, and the Prohibition party.

The M.E. Church and its successors have also tried to improve city life by providing services to the larger community. In 1908, Methodist Hospital, now the largest health care facility in the state, opened with 65 beds. Local Methodists brought to Indianapolis in 1928, and in 1937 established Fletcher Place Community Center on the city’s south side.

In 1939, the Methodist Protestant Church reunited with its parent body along with the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, which had formed in 1844 when the issue of slavery divided the church. While Indianapolis had no Southern Methodist congregations, the Methodist Protestants brought two local churches into the newly formed Methodist Church. Around the time of this merger, the two Indianapolis German-speaking congregations were integrated into the mainstream.

The United Methodist Merger and Recent Developments, 1968-

In 1968, a merger between the Methodist Church with the Evangelical United Brethren created the United Methodist Church. The E.U.B. Church was itself the result of a merger of the Evangelical Church (formerly the Evangelical Association) with the Church of the United Brethren in Christ. Both these groups were formed early in the 19th century by German-speaking Americans who shared a similar style, theology, and organization with English-speaking Methodists.

The first United Brethren congregation in Indianapolis formed in 1850 and built its first church the following year at Ohio and New Jersey streets. In 1905, they established Indiana Central College—now the University of Indianapolis—just south of the city. The Evangelical Association’s first local congregation came together in 1853 and erected a church on Ohio Street near its intersection with New Jersey in 1855. The two German denominations combined in 1946 to form the E.U.B. Church and later brought four Indianapolis congregations into the United Methodist fold. With the 1968 merger, Black Indianapolis Methodist Church congregations were fully integrated into the United Methodist Church’s organizational structure.

Like other mainline denominations, the United Methodist Church’s local and national membership has declined since the late 1960s. In 1980,66 congregations existed in Indianapolis, and by 2010,51 remained. Yet, membership in Indianapolis during the same time period remained relatively stable, down around 7 percent from 1980, while other mainline denominations like the Presbyterians lost nearly 42 percent of their members. Suburbanization has forced many church closures, moves, and consolidations. Nevertheless, new churches continue to flourish in outlying areas, and the bulk of Indianapolis United Methodists are in these white, suburban congregations.

Significantly, while the local membership of the United Methodist Church erodes, all three African American denominations have shown recent growth. The African Methodist Episcopal Church currently has 7 local congregations with about 4,000 members. Bethel AME, which left its historic downtown location for in 2018, remains a large and active congregation. The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church has 5 Indianapolis congregations with about 1,500 members. The Colored Methodist Episcopal Church, now known as the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, includes 10 congregations. Phillips Temple, which moved from its near west side location to 34th Street and Washington Boulevard, remains the largest of the CME churches. Altogether the CME has about 3,000 local members.

All the Black Methodist denominations share a common liturgical tradition that maintains many of the older usages of 19th-century Methodism. They have also maintained an emphasis on evangelism as well as a strong commitment to improving the Indianapolis African American community. Following cuts in government programs in the 1980s, Black Methodists have increasingly tried to provide relief programs such as clothing banks and food pantries. Black Methodist clergy of all four denominations united in 1990 in the Black Methodist Ministerial Forum to address the concerns of the city’s Black residents on such issues as police shootings and racism.

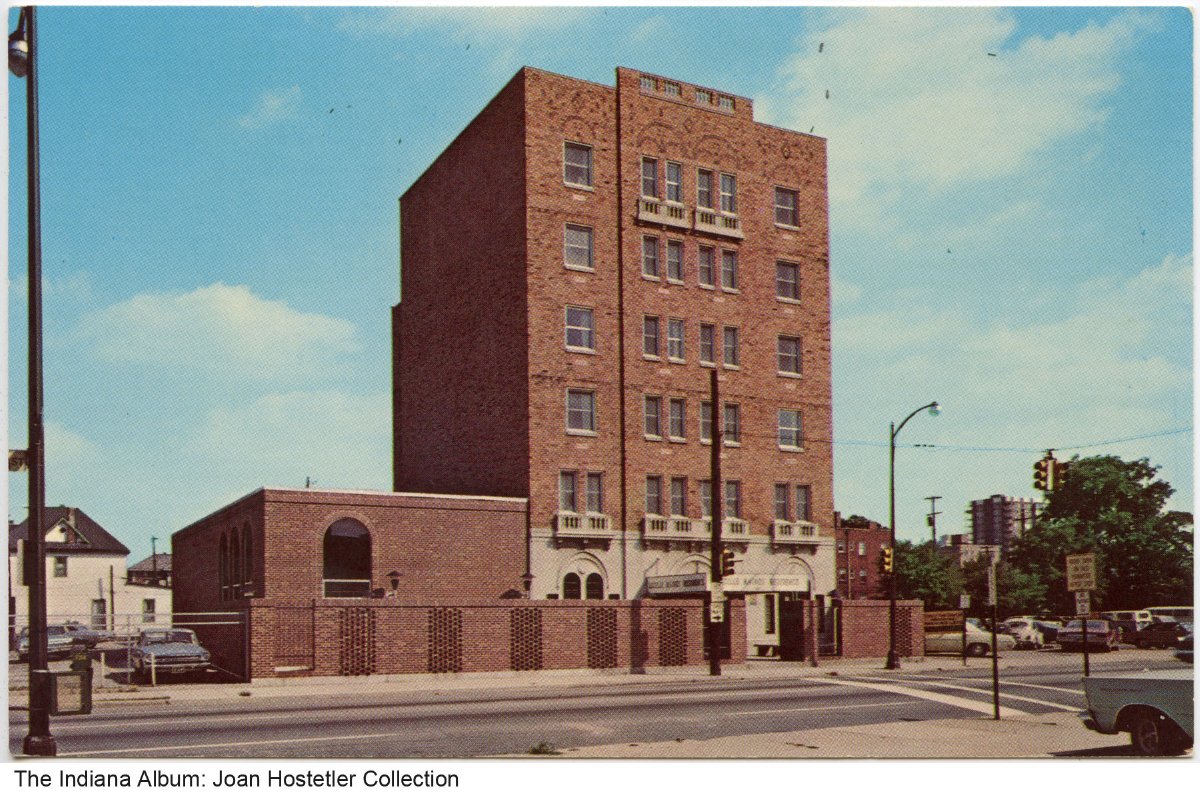

United Methodists also have remained active in providing city residents with social services. In 1970, United Methodists opened the Lucille Raines Residence for Women, which houses a variety of women with special needs in a downtown apartment building. They also established a community center in the area. Local United Methodists are involved in such activities as community development and education, food banks and immigration services, and addiction recovery support.

The United Methodist Church remains the largest Protestant denomination in Indianapolis. While only three city congregations are significantly integrated, six predominantly Black U.M. congregations remain active. Today, in addition to the African American congregations, the United Methodist Church has one local Korean church.

Each local United Methodist Church sends its clergy and an equal number of lay delegates to the South Indiana Conference, which formally holds title to the local church property. The Indiana area bishop also has offices in the city, from which he presides over both the South and North Indiana Conferences. These bodies both send delegates to the quadrennial General Conference to make policy for the denomination.

The United Methodist Church is an important member of the , through which it shares projects with many other Indianapolis Protestant groups. Indianapolis Methodists’ active role in the National Council of Churches of Christ brought criticism by local fundamentalists unhappy with the NCCC’s liberal policies.

Entering the 21st century, the United Methodist Church was embroiled in controversy over the denomination’s Book of Discipline and statements on human sexuality regarding same-sex marriage. While many American United Methodists were willing to liberalize the denomination’s doctrine, a conservative minority allied with global United Methodists (especially in Africa) wished to retain the more traditional statements. By 2020, the denomination seemed poised to fracture, which would force congregations to decide with which branch of Methodism they would belong. One plan for disunion was dubbed “the Indianapolis Plan” after a meeting held in the Circle City. The plan envisioned a Traditionalist United Methodist Church that would maintain restrictions on same-sex marriages and ordination of gay clergy and the creation of a separate Centrist/Progressive United Methodist Church that would remove those restrictions. The Centrist/Progressive denomination would also teach that the practice of homosexuality is not incompatible with the Christian faith. The COVID-19 pandemic put at least a temporary halt to the issue.

Despite denominational divisions, all Indianapolis Methodists share a common history of deep community involvement and religious commitment. They helped lay the foundations of Indianapolis community life and have helped guide its development. Religiously and socially, Methodism continues to play a major role in Indianapolis.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.