Photo info …

Credit: Indianapolis Public LibraryView Source

(Feb. 10, 1865-Sept. 23, 1955). Emma Christy was born in Salem, Washington County, Indiana, to William W. Christy and Hester Shrewsberry. Her father was born a free man of color in North Carolina and came to Washington County in the 1820s. Her mother was born enslaved but was freed at age 5 when her owners settled in Washington County, Indiana. Indiana state law stipulated that all enslaved people be “freed” upon entry to the state.

Anti-Black sentiment led the Christy’s to leave Washington County one month after Emma was born in 1865. Negative attitudes toward the Black community had increased with the growth of the African American population and had intensified in 1863 with the Emancipation Proclamation and . When Confederate General John Hunt Morgan’s cavalrymen crossed the Ohio River into Indiana in July, they threatened to send any African American people they encountered back south into enslavement. White residents in the Salem area, in turn, engaged in patterns of intimidation, violence, and murder against Black inhabitants during the final years of the Civil War. The Christy’s, who by then had become landowners, sold their property and moved to Indianapolis.

Emma Christy’s father worked as a coachman at an express office before opening a laundry business in 1875. He applied unsuccessfully for employment as a police officer when the City of Indianapolis opened these positions to African Americans in May 1876.

By then, Emma Christy was enrolled in the public school system. Her uncle Levi Christy was the principal of School No. 19 in 1876. He left the system in 1885 to become editor and co-owner of the , the second African American newspaper in Indianapolis.

As a young woman, Emma Christy volunteered at the , of which she was a lifelong member. She graduated from Booker T. Washington Public School No. 17 and graduated from in 1884.

She then went to work at her father’s laundry business and married David M. Baker, on July 9, 1889. She and Baker had one son, John D. Baker, who was born in 1892 but died at age seven. By 1910, Emma Baker took over the day-to-day operation of her father’s laundry business.

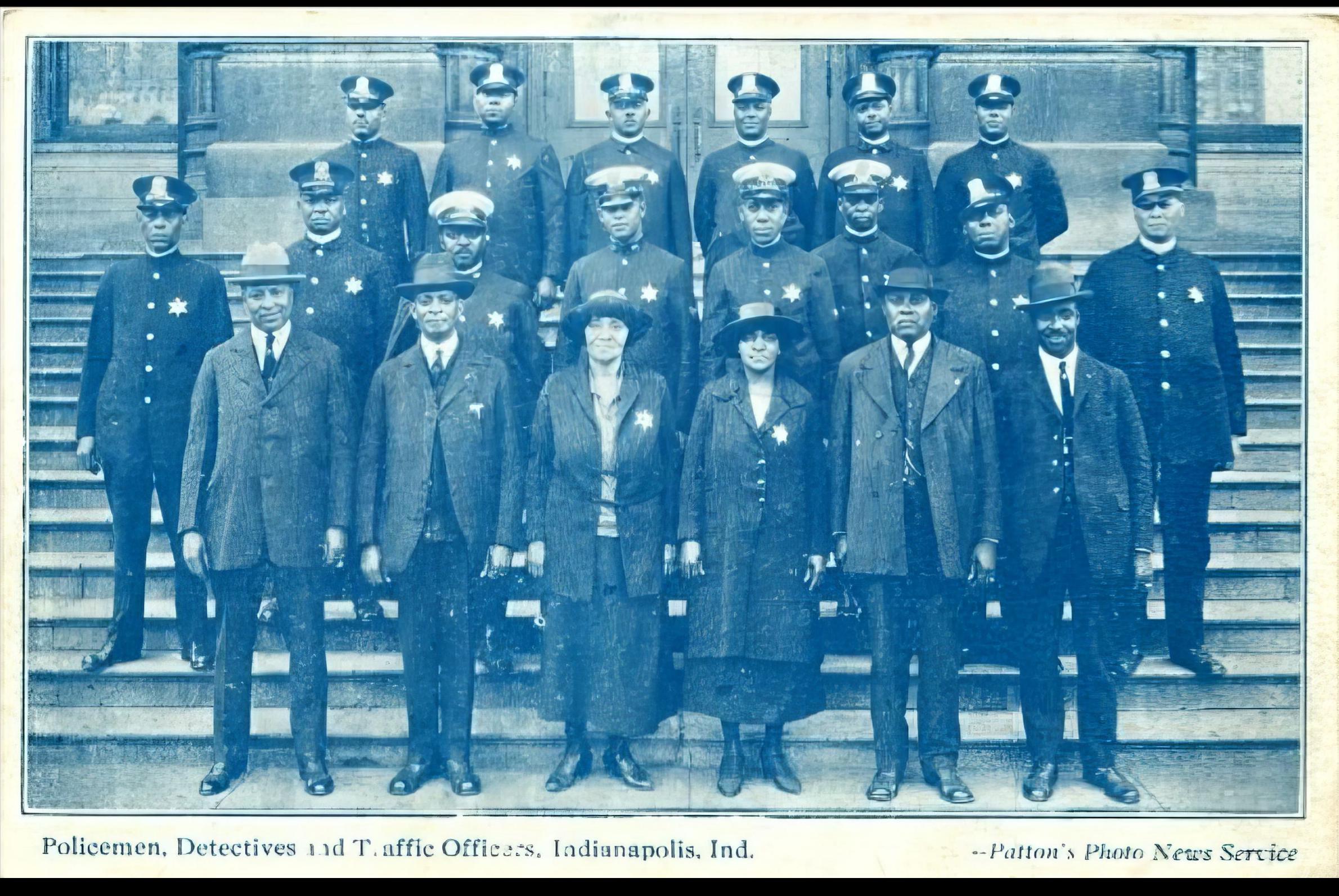

In 1918, the Indianapolis Board of Public Safety appointed Baker to the police force based on her rapport within the African American community. She and Mary Mays, another native of Salem, Indiana, became the first two Black women appointed to the force, working for Sergeant (see also ).

Baker and Mays worked from 1:30 p.m. to 11:30 a.m., patrolling all African American neighborhoods in Indianapolis, particularly . Dressed in plain clothes to avoid discovery, the two policewomen worked to prevent shoplifting and to protect young women and girls of the community from preying men.

Between 1918 and 1919, Baker and Mays successfully led investigations that led to the arrest of three women dancing “cabaret-style” at a club on Indiana Avenue, 29 people violating the law and illegally gambling, and a man forcing children to sing and dance on downtown Indianapolis streets.

In 1922, Baker was transferred from police headquarters to the Juvenile Court in the Probation Department located at the Marion County Courthouse. By 1924, the problem of underage youth frequenting public dance halls, a violation of Indianapolis’ dance hall ordinance passed in March 1906, had become increasingly problematic for the juvenile court system, which heard the cases of these youth who had been apprehended by policewomen and dance matrons who patrolled the venues. Baker was one of those policewomen who served as a dance matron. She attempted to enforce the ordinance’s provisions that prohibited girls under 18 and boys under 16 from entering a public dance hall; prohibited “cheek-to-cheek dancing”; banned smoking and alcoholic beverages from dance halls; and enforced gents to hold partners in a refined and “gingery” manner. That year she earned a salary of $1,733.50 a year.

Indianapolis’ budget faced serious hardship by 1926. In December 1926, the Board of Public Safety informed the police department that the city budget for 1927 provided for the salaries of only 5 women officers, who would be transferred from patrol to clerical positions. The police force terminated 17 of 22 women officers, including Baker.

All 17 female police officers who lost their positions hired an attorney to file a tort claim protesting their dismissal. Their suit resulted in a permanent injunction against the Board of Safety preventing their dismissal on the grounds of its failure to allow the women a trial before the board. It also stipulated their reinstatement to the force in January 1927. Though back to work, the officers did not receive a salary from their reinstatement to the time the case came before the Indiana Supreme Court. The women, therefore, chose to work without pay, refusing to give up their jobs.

On May 29, 1928, the Indiana Supreme Court affirmed the Marion County Superior Court decision that the Indianapolis policewomen were entitled to their salaries as well as back pay for the period from January 1927 through May 1928.

On June 11, 1932, the credited Baker with saving numerous juveniles from a life of crime through her wise counsel. Baker estimated she had handled over 3,000 juvenile cases through her work at the Juvenile Court since 1923.

Officer Baker occasionally spoke publicly about juvenile delinquency and ways to approach the problem and perhaps stem its progression to criminal activity. The Indianapolis Police Department established a new crime prevention bureau for juvenile law violators in 1932 (See ).

Baker retired from the police force on August 5, 1939. She then pivoted to politics. In October 1947, Baker became a member of a 70-person committee aimed at getting Republican William H. Wemmer elected mayor. Eight years later, Baker died and was buried at Crown Hill Cemetery.

In 2003, IPD officer Marilyn Gurnell successfully led an effort to raise money for a headstone for Baker, her husband, and her son. The headstone was dedicated on September 23, 2003, the 56th anniversary of her death. Her gravesite is part of a historic tour of African Africans buried in Crown Hill Cemetery.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.