Although Indianapolis already had some authority to regulate against factories in residential areas by 1905, a 1921 state law gave Indiana cities jurisdiction over land planning and zoning for the first time.

Following the legislation, the Common Council created a 10-member volunteer City Plan Commission and passed the city’s first zoning ordinance in 1922. This ordinance, which affected only new development, established five types of “use districts,” including residential dwelling, apartment, business, and two kinds of industrial districts. The City Plan Commission had broad powers to create the boundaries of use districts as well as hear zoning appeals, and a commissioner of buildings enforced the ordinance. In 1935, state law required the commission to create a master plan for the city as well as subdivisions five miles outside of the city limits.

The intent of the zoning legislation was to protect neighborhoods from “undesirable elements” and to avoid the creation of “blighted” areas through stabilized use. Generally, the central downtown core was designated for business; the north and east sides were zoned almost exclusively residential; and the west and south sides included a mix of industrial, business, and residential uses. Initially, there were relatively few zoning disputes. The Common Council could amend zoning ordinances or overturn decisions, but these powers were rarely exercised before World War II.

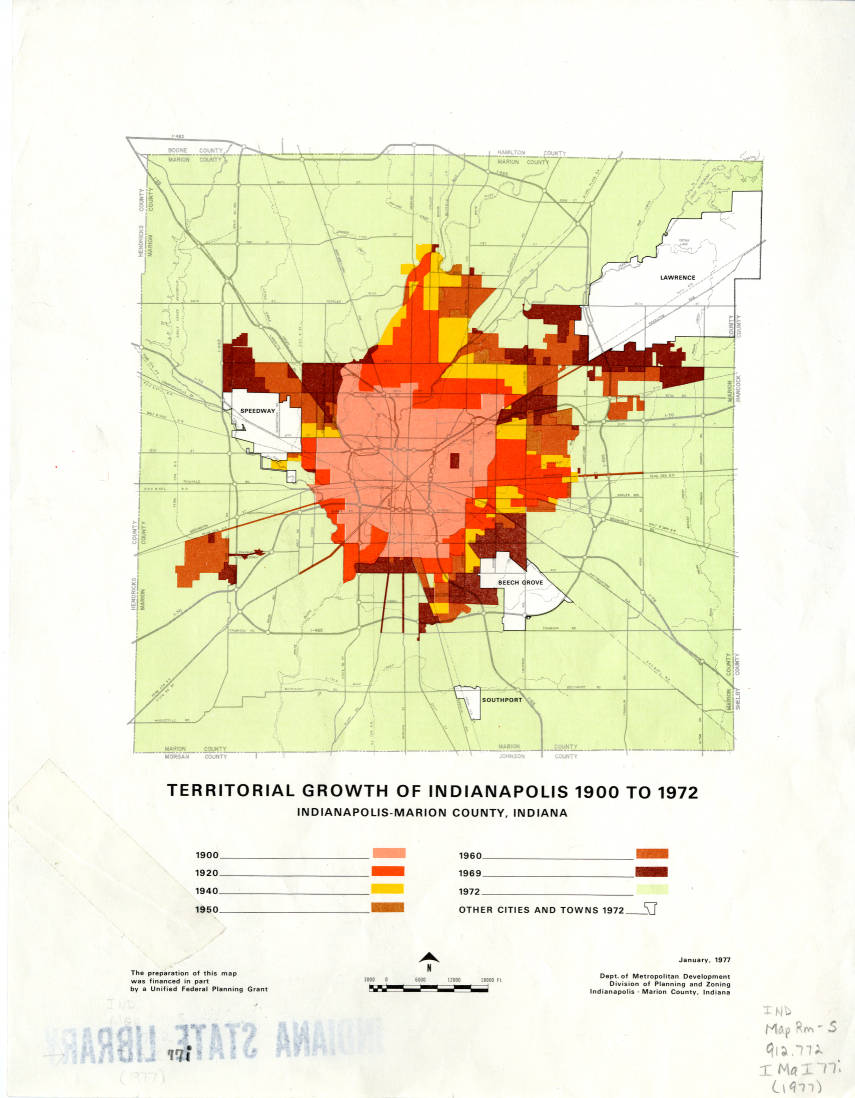

During and after World War II, city planners, concerned by a perceived downfall in urban life and decentralization, successfully lobbied for professional staff to conduct postwar planning (see ). After a large amount of tinkering with city zoning ordinances, the state legislature consolidated the Indianapolis and Marion County planning and zoning functions in 1955 when it adopted the Metropolitan Planning Law and created the Metropolitan Planning Commission of Marion County.

As Indianapolis grew, so did public discontent with zoning decisions and enforcement of violations. Residents throughout the city called for a reevaluation of the zoning ordinances.

Under , effective in 1970, the (MDC), a supervisory body of the (DMD), succeeded the Metropolitan Planning Commission. To maintain zoning functions, the DMD needed to adopt and implement a Comprehensive Plan for Marion County, which like earlier master plans, guides and regulates the county’s growth by designating geographic boundaries of land uses. Under state law, the following considerations must guide land use decisions: “assuring adequate life, air, convenience of access, and safety from fire, flood, and other dangers; lessening or avoiding congestion of public ways; and promoting public health, safety, comfort, morals, convenience, and general welfare.”

The Comprehensive Plan was actually a series of studies corresponding to Marion County townships, Indianapolis neighborhoods, and the Indianapolis central business district. Originally designed to be revised every 20 years, the plan required revision approximately every five years because of the rapid pace of development in the Indianapolis metropolitan area since the 1970s. As of the 1990s, each component of the plan is the result of a lengthy process of discussion between neighborhood organizations, developers, residents, and DMD planning staff. Planners use the information gained from these discussions to create a map and text that describe current land uses and recommend future uses. The segments of the Comprehensive Plan are subject to a public hearing and approval by the MDC.

Property in Marion County is zoned for one of the following types of use: commercial, residential, central business district, industrial, airport, park, hospital, university, and various special uses such as schools and churches. Secondary zoning districts also define restrictions or requirements for property use. These districts include the historic preservation, airspace, and regional center districts, both of which require a special design review, as well as flood control and gravel pit designations. Subsequent amendments created a wellfield overlay district, to protect Indianapolis’ drinking water.

Land use for a particular parcel of real estate may be changed either through a rezoning of the site or a variance in zoning. A rezoning makes a permanent and legal change in the approved use of the property in question. A variance is an administrative decision, which does not change the zoning of the land but permits the current owner to use the property for a specific purpose, not allowed by the zoning. Landowners must file a petition for a rezoning or variance and notify affected landowners and residents, who are allowed to give testimony at a public hearing. DMD staff prepare recommendations for all rezoning and variance requests based upon site reviews and compliance with Comprehensive Plan provisions, sound planning practice, and municipal zoning ordinances.

The Metropolitan Development Commission decides rezoning requests, but those can be called up for hearing by . The Metropolitan Board of Zoning Appeals hears requests for zoning variances. The board may allow or deny a variance pertaining to use, height, bulk, area, and on special exceptions to a zoning ordinance. It has countywide jurisdiction except for the municipalities of , , and , which operate their own Boards of Zoning Appeals, with some members appointed by the MDC. Zoning decisions and policies are implemented through a system of permits and inspections conducted by staff of the Department of Business and Neighborhood Services (BNS). Property owners not in compliance with zoning regulations can be fined.

Since the 1970s, the city government has increasingly responded to citizens’ zoning concerns. encouraged more community involvement in planning and zoning by including neighborhood groups in the Comprehensive Plan process. The also strengthened citizen access by appointing township administrators who, among other things, act as a conduit between DMD staff and community groups. Each subsequent Mayor has kept this staff of liaisons, although with different titles.

Zoning staff also improved the public notification hearing process for neighborhood and surrounding property owners. Staff also created a supplemental review process to increase the level of communication and interaction with residents and petitioners prior to scheduling public hearings for certain threshold petitions.

For much of the 1980s and 1990s, amendments to the zoning ordinance were done as individual Amending Ordinances. The changes were proposed for a variety of reasons, ranging from desired policy changes to changes in technology and land use. Changes were typically proposed by the DMD staff, who solicited public input through a series of meetings. Ultimately, the changes were subject to public hearing and approval by the MDC and the City-County Council.

In the early 2000s, DMD initiated a major comprehensive overhaul of all of the zoning ordinances. The effort was called Indy Rezone – an effort aimed at making a more livable and sustainable city. DMD played a critical role in this initiative by leading the facilitation of dozens of discussions across multiple stakeholder groups and managing the efforts and outcomes of the Steering Committee over a two and half year timeframe. DMD served a leadership role, by engaging focus groups at round tables, technical task forces, and the multi-stakeholder, 30-person Steering Committee.

Outreach efforts were aimed at ensuring that any ordinance changes were thoughtfully developed and publically vetted across many groups and neighborhood scenarios. Staff focused on increasing the public’s understanding of topics, such as transportation choices; equitable, affordable housing; economic competitiveness; green investment; natural resource protection; and neighborhood invigoration. This understanding was then leveraged into meaningful contributions by developing and facilitating diverse public input mechanisms. Indy Rezone will shape Indy’s built environment into the kinds of places people want to work, live, and play for the next several decades.

Indy Rezone was adopted in 2015 and went into effect on April 1, 2016. The ordinance is regularly reviewed and updated through amending ordinances.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.