The first Conference on Women’s Rights took place in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848. Its primary issues of women’s property rights and female suffrage set the agenda for the battle for women’s rights in Indianapolis.

A local woman first entered the public debate on women’s rights in 1850 as the male delegates at the state’s constitutional convention bickered over whether or not married women should have the right to prevent husbands from selling their wives’ personal property. Indianapolis poet supported the constitutional changes in newspaper articles published throughout the state, which explained the grievances of women’s status under the current law.

Although the convention delegates did not include the property rights clause in the revised constitution, Bolton organized a testimonial in honor of its supporter, Robert Dale Owen. The following year when Owen helped pass a law that gave widows the right to bequeath their family property, a right that formerly belonged only to men, he praised Bolton’s continuing efforts as instrumental in bringing about the change.

Although the Indiana Woman’s Rights Association (IWRA) was formed in 1851, no Indianapolis women were among its founders. However, in November 1854, when the city hosted the first of many Woman’s Rights conventions at the Masonic Hall, Mrs. Priscilla H. Drake, a longtime Indianapolis resident, was nominated as the group’s vice president. That year nationally known suffragist Lucy Stone gave a series of lectures in the city on women’s right to employment, self-support, and suffrage. Attendance was high, but at least some of the participants were more interested in Stone’s “Bloomer costume” than in her discourse.

The following year, Indianapolis heard the famous suffragists Frances Gage, Lucretia Mott, and Ernestine L. Rose at the Woman’s Rights Convention. In 1856, local newswoman Sarah Underhill, publisher of the Ladies Tribune, a short-lived temperance paper, spoke at the convention about the effects that the legal disabilities of women had on society. That same year the IWSA officially declared that the “right of suffrage is [the] cornerstone” to acquiring equal rights, and its members increased their efforts to gain suffrage.

In 1859, three members of the IWRA presented a petition to the General Assembly asking for suffrage and increased property rights. Although the association’s minutes called the presentation “a grand success,” the local press reported that the gathering turned into a “noisy and foolish meeting.” An anti-suffrage article in the next day’s asserted that women did not need the vote and advised them to go home where their rights would be “safe in the true love of your good man.”

During the Civil War, even the most ardent suffragists temporarily suspended their pursuit of women’s rights to give full attention to their country’s needs. However, the war provided ample opportunities for women to demonstrate that they deserved equal legal treatment. Women capably managed property, businesses, and manufactories while their men were away. Indianapolis women manufactured literally tons of blankets, socks, gloves, wool shirts, and “drawers” at the request of Governor , nursed the sick at local hospitals, and in November 1863, earned $40,000 ($822,000 in 2020) at the state’s first Sanitary Fair, called the “Ladies Soldiers’ Aid Festival.”

When the war ended most women went back to the domestic sphere but an increasing number began to wonder why few people recognized their contributions. Many women objected to the use of the word “male” in the 14th Amendment, which, for the first time, placed gender-exclusive language in the U.S. Constitution. When the 15th Amendment guaranteed the vote to African American males, women grew increasingly bitter over their own exclusion from the polls.

The first Woman’s Rights Convention in Indianapolis after the Civil War was held in 1869. The IWRA chose ministers Henry Blanchard, E. P. Ingersoll, and J. Cummings Smith, and Mrs. Erie Locke, all from Indianapolis, as delegates to the Western Woman’s Suffrage Association to be held in Chicago. The IWRA also changed its name to the Indiana Woman’s Suffrage Association (IWSA).

The 1870s marked a significant increase in local participation in the suffrage and women’s rights movement. In 1870, the Indianapolis Tumverein, a German organization, split over the issue of women’s rights, and the more liberal members withdrew to form the Socialer Turnverein (See ). Susan B. Anthony spoke at the 1870 convention on women’s rights, and members outlined a plan that called for a mass meeting of women’s rights activists and the presentation of a suffrage petition to the General Assembly.

On January 20, 1871, Amanda M. Way and Emma B. Swank (both listed as Indianapolis residents in the IWSA minutes) presented the suffrage petition to a joint session of the General Assembly. Although this legislature rebuffed their efforts, the suffrage association began regularly to send written memorials to the assembly requesting universal suffrage, married women’s property control, and equal pay for equal work. They also began to work for the election of candidates favorable to their causes, especially for men who supported female suffrage.

In 1873, the legislature made women eligible to hold any office elected by the General Assembly or appointed by the governor and granted them the ability to control the real estate of an insane spouse. By 1875, in an effort to appear more amenable to the women’s rights movement, state representatives allowed suffragists to use their chambers for evening gatherings. Elizabeth Cady Stanton spoke there in the 1870s, as did , widow of former governor David Wallace.

Legislators decreed in 1877 that the managing board of the women’s prison should consist only of women. This concession was requested by the state suffrage association, whose vice-president was Mary Haggart, the publisher of the Woman’s Tribune, an Indianapolis weekly paper devoted to women’s rights.

In 1878, the women of the city formed their own suffrage association, the Indianapolis Equal Suffrage Society. Founding members included , founder of the Girls’ Classical School, well-known teacher , and Zerelda Wallace. Both Wallace and Sewall became influential suffragists on a national scale, working with Susan B. Anthony’s National Woman’s Suffrage Association. Wallace, a member of the , was also influential in reversing the antisuffrage policy of that group in the 1870s.

In the 1880s, Indiana women gained additional property rights and briefly thought they had won the suffrage battle as well. Women gained absolute control of their own property in 1881 as well as the ability to sue alone in actions regarding it. On April 8, 1881, after receiving a memorial in favor of suffrage from Indianapolis and 30 Indiana counties, and a call to action from Governor Albert G. Porter, the General Assembly approved a resolution to give women the franchise through an amendment to the state constitution.

But amendments were required to pass two consecutive sessions of the legislature, and in the following session, as the suffrage issue became linked with a temperance amendment, both resolutions failed to pass the now Democratic-controlled legislature. Three years later female suffrage was again considered and rejected in both houses of the General Assembly.

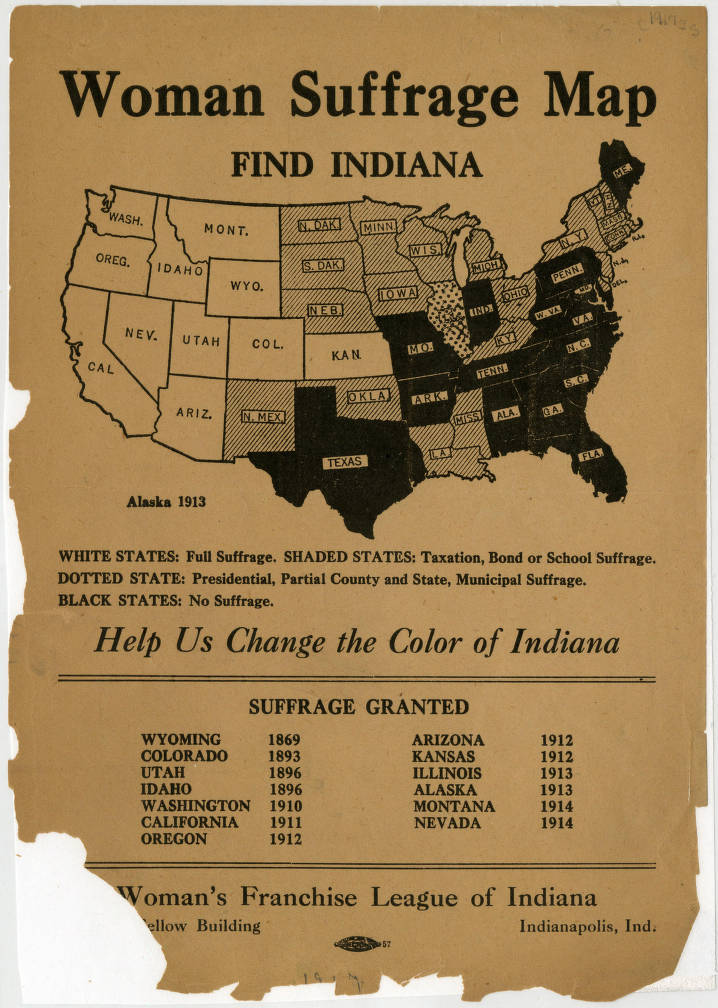

By the turn of the century Indianapolis women, like women in other states, had made significant, although piecemeal, gains in property rights, but suffrage continued to elude them. In 1890, Wyoming entered the Union as the first state to include women’s suffrage in its state constitution since New Jersey, which had enfranchised women in 1776 only to repeal that right in 1807.

Indianapolis made less significant advances in the 1890s. Indiana suffragist Ida Husted Harper joined the editorial staff of the Indianapolis News in 1890. In 1897, Susan B. Anthony asked a joint session of the Indiana General Assembly to request a women’s suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Two years later Anthony was working on the six-volume when she and other officers of the National Woman’s Suffrage Association met in Plymouth Church in Indianapolis.

Over the next 20 years, no fewer than 10 women’s suffrage bills were proposed in the Indiana legislature, and each time the item was either rejected or not considered. Concurrently the Indianapolis suffragists were finding new leaders and new approaches in their fights to acquire the vote. In the 1900s, May Wright Sewall founded the Indiana Federation of Clubs which, although not a suffrage association, increased women’s power by teaching them how to organize and by placing their names in the public arena.

In 1909, Dr. and the Indiana Federation of Clubs led a movement that placed on the Indianapolis Board of School Commissioners. After this success, the group attempted to gain women the right to vote in school board elections throughout the state. Some women, including the wife of Governor Thomas Marshall, opposed female suffrage in federal elections, believing “men are more capable.” Most, however, generally approved of women’s involvement in school board elections. Despite the popularity of the movement, women did not gain even this right.

By the early 1900s, African American women’s involvement in the suffrage movement began to grow. The first African American branch of the Equal Suffrage Association of Indiana was formed in Indianapolis in 1912. Indianapolis resident became the first president of the branch, stating, “We all feel that colored women have need for the ballot that white women have, and a great many needs that they have not.”

In 1914, Mrs. , a director of , helped found the Legislative Council of Indiana Women, a lobbying group of several women’s groups and clubs. The council’s 1,000 members included teacher and author and president Dr. Amelia Keller. By 1917, the council had persuaded many prominent Indianapolis citizens to telegraph the five U.S. senators deemed most likely to vote in favor of a constitutional amendment for universal suffrage.

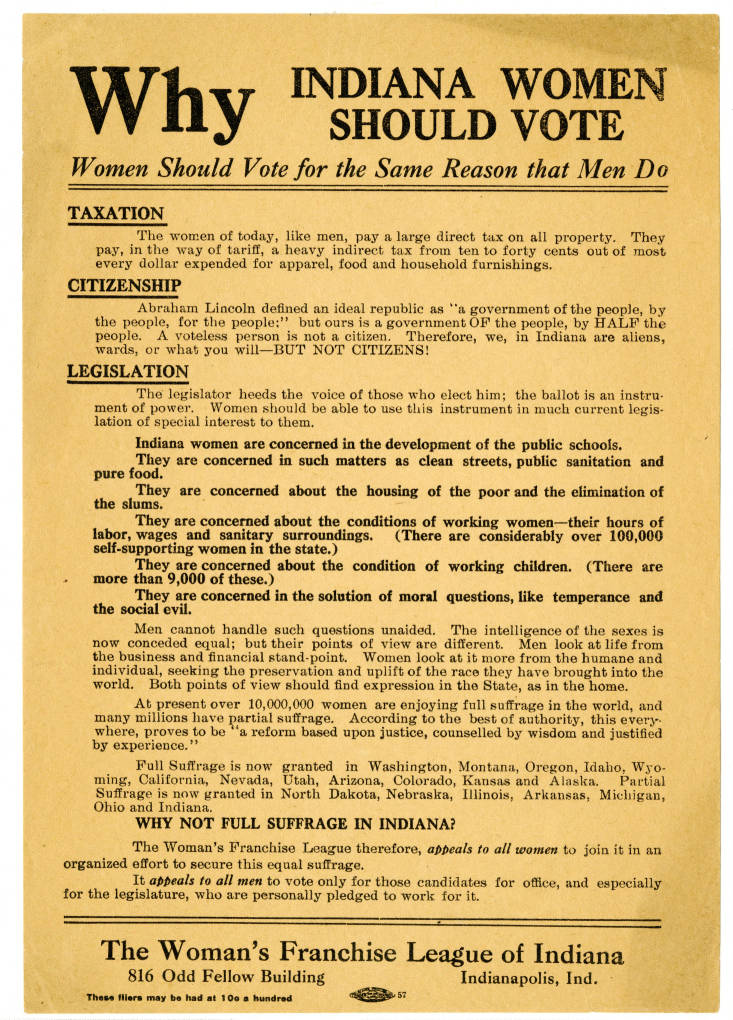

Again in 1917, Indiana women briefly celebrated their potential enfranchisement when the Indiana State Legislature voted in favor of partial suffrage for Hoosier women. Locally, the Women’s Franchise League offered home study classes to educate women on the voting process and the issues before the electorate. When the Indiana Supreme Court declared the bill unconstitutional, women’s groups, locally and across the nation, again took up the suffrage banner. Sara Lauter of Indianapolis, president of the Woman’s Franchise League, spoke from a “suffrage wagon” in New York City and took turns with others in the group speaking locally “whenever we could get two people together to listen.”

Finally, in 1919, the years of hard work by two generations of women reached fruition when Congress passed a new suffrage bill. A special session of the Indiana General Assembly ratified the 19th Amendment on January 16, 1920. In Indianapolis, the Woman’s Franchise League held a Ratification Opera performing songs such as “Twas the Night ‘Fore Election” and “For I’ve Struggled Long in the Cause, Mother.” A special state election in September 1921 granted women the vote at the state level.

The 19th Amendment was an important win, providing many women the right to finally vote and have more power to effect change. More work was needed, however, to provide equal opportunities for African American and minority women to vote without facing racial violence and exclusionary barriers.

In Indianapolis, African American women did indeed vote. Records indicate that Black women helped the Republican Party in 1920 with evidence of heavy turnout for registration and voting in the 1920 and 1924 elections. records show no indication of systemic voter suppression in Indianapolis. Still, legal protection against racial discrimination in voting would not be secured for another 45 years with the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.