Photo info …

Credit: Indiana Journalism Hall of FameView Source

(March 23 1909-July 1, 1997). Born in 1909 in Marshfield, Wisconsin, Charles Werner attended Oklahoma City University with no formal art training. His journalism career began in 1930 when he served as an artist, photographer, and reporter at the in Missouri. In 1935, he joined the staff of the , becoming an editorial cartoonist two years later.

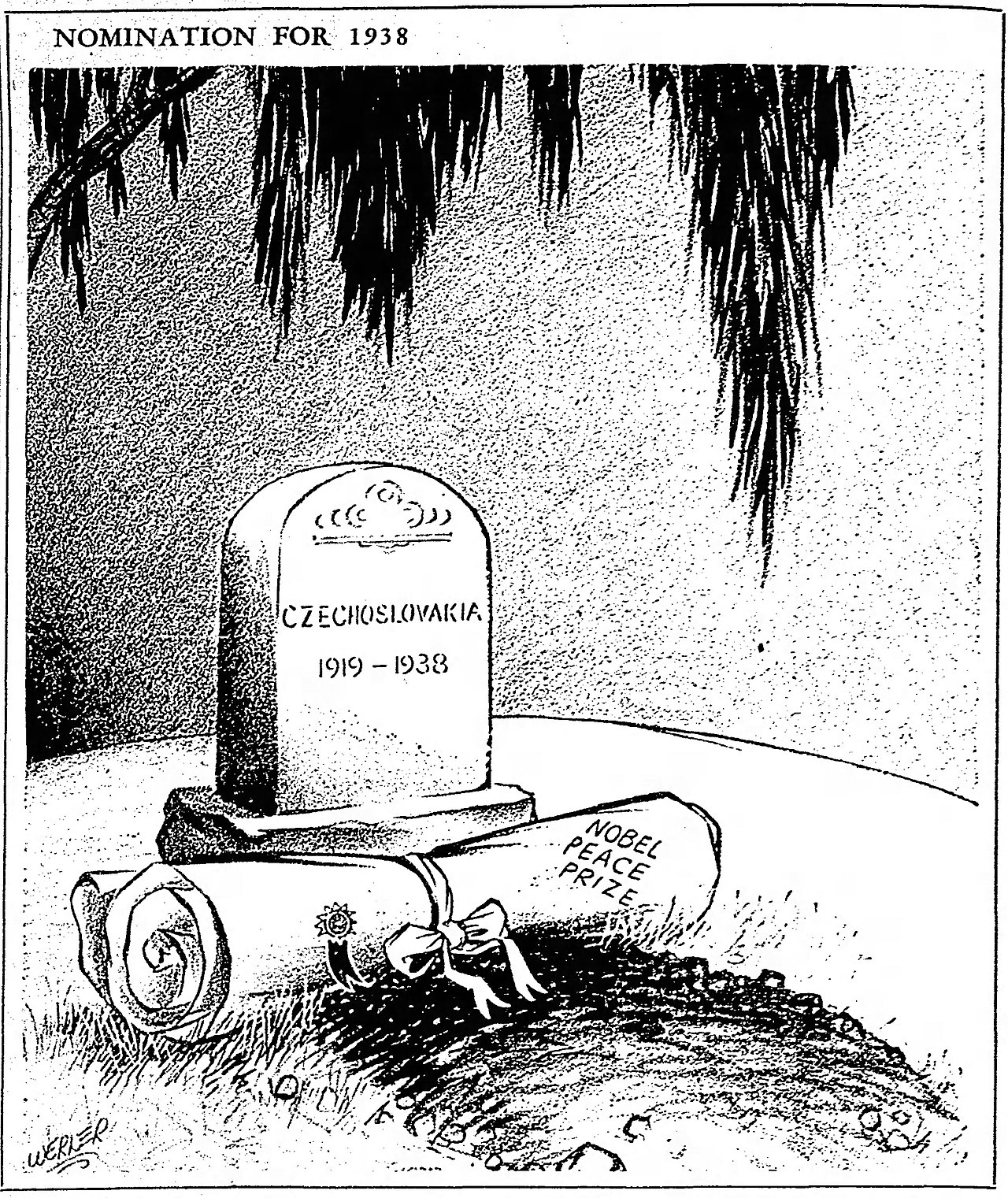

It was at the where Werner, was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1939, the youngest person to win the prize for editorial cartooning. Published on October 6, 1938, the cartoon, titled “Nomination for 1938,” was a commentary on the Munich Agreement that transferred Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland to Adolf Hitler’s Germany. Through a simple yet forceful image, Werner drew a gravestone marked “Czechoslovakia/1919-1938” upon which was placed the Nobel Peace Prize.

Werner moved to Chicago in 1941 where he served as the chief editorial cartoonist for the . Though Werner did not have formal art training, out of curiosity he did attend the Chicago Art Institute and eventually became an instructor there. His cartoons for the were well received, but a disagreement over editorial policy led him to move to Indianapolis in 1947, where he joined the and remained until he retired in 1994.

Werner contributed enormously to the by bringing national recognition to the paper’s editorial pages. In the first three decades after World War II, his powerful and poignant cartoons often appeared on page one.

The Star’s publisher noted that the cartoons Werner produced day after day “were an informed, sometimes caustic, but an accurate commentary on his world. Few have done it so well.” Werner believed that knowledge of the Bible, mythology, and Shakespeare was critical for framing ideas and forming analogies that reflected contemporary situations through the art of cartooning. He asserted that cartoons be fact-based. According to Werner, direct, critical cartooning with satire and ridicule as a base, led to a successful cartoon.

His cartoons touched upon national and international affairs, as well as state and city politics. Due to his deep commitment to community affairs, he deliberately focused 40 percent of his work on those matters. He declined offers to syndicate his material because it would have forced him to divert his attention away from the local themes to the national and global matters.

Werner earned numerous awards while at the . Honors came from the National Service Clubs, the Society of Professional Journalists, and the National Foundation for Highway Safety. He received the Sigma Delta Chi Award for excellence in journalism in 1943 and seven Freedom Foundation awards from 1951 to 1963. In 1969, Werner was recognized as one of the world’s six best cartoonists at the International Salon of Cartoons in Montreal. Yet the award he won in 1951 from the National Headliners Club for outstanding editorial cartoons was purportedly his most cherished, eclipsing his Pulitzer Prize honor.

Werner’s work has been displayed nationally and reproduced in textbooks and historical collections. His work is archived in several presidential libraries and state archives, at the Library of Congress, at the Special Collections Research Center at New York’s Syracuse University, and the Indianapolis Special Collections Room at the .

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.