(Feb. 25, 1935-May 5, 2017). William George Ryder Jr. was born in Baskett, Kentucky, to William George Ryder Sr. and Nannie Marie Pickle Ryder. He grew up in Evansville, Indiana, where he graduated as the senior class vice president of the segregated Lincoln High School in 1953.

After high school, Ryder joined the Air Force, serving an aircraft electrician. During his military service, he took up boxing, earning a 12-0 record in his middleweight category.

Upon release from the military, Ryder traveled from Michigan, through the Mojave Desert, until he arrived in Los Angeles, California. He attended the University of California at Los Angeles but eventually came to Indianapolis. He married graduate Betty Jean Hill on July 17, 1965. The couple had one child.

In Indianapolis, Ryder worked full-time as a stationary engineer apprentice, becoming first African American employee. He attended on a full scholarship to its evening program, becoming the first African American to receive the financial award.

Upon graduation, he founded Ryder Graphics, Inc. in 1970. However, Ryder found business ownership a challenge. Competition against established printing companies with their extensive social and political connections became an insurmountable challenge. His firm was also a minority enterprise in a business community that was dominated by whites.

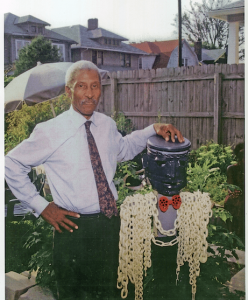

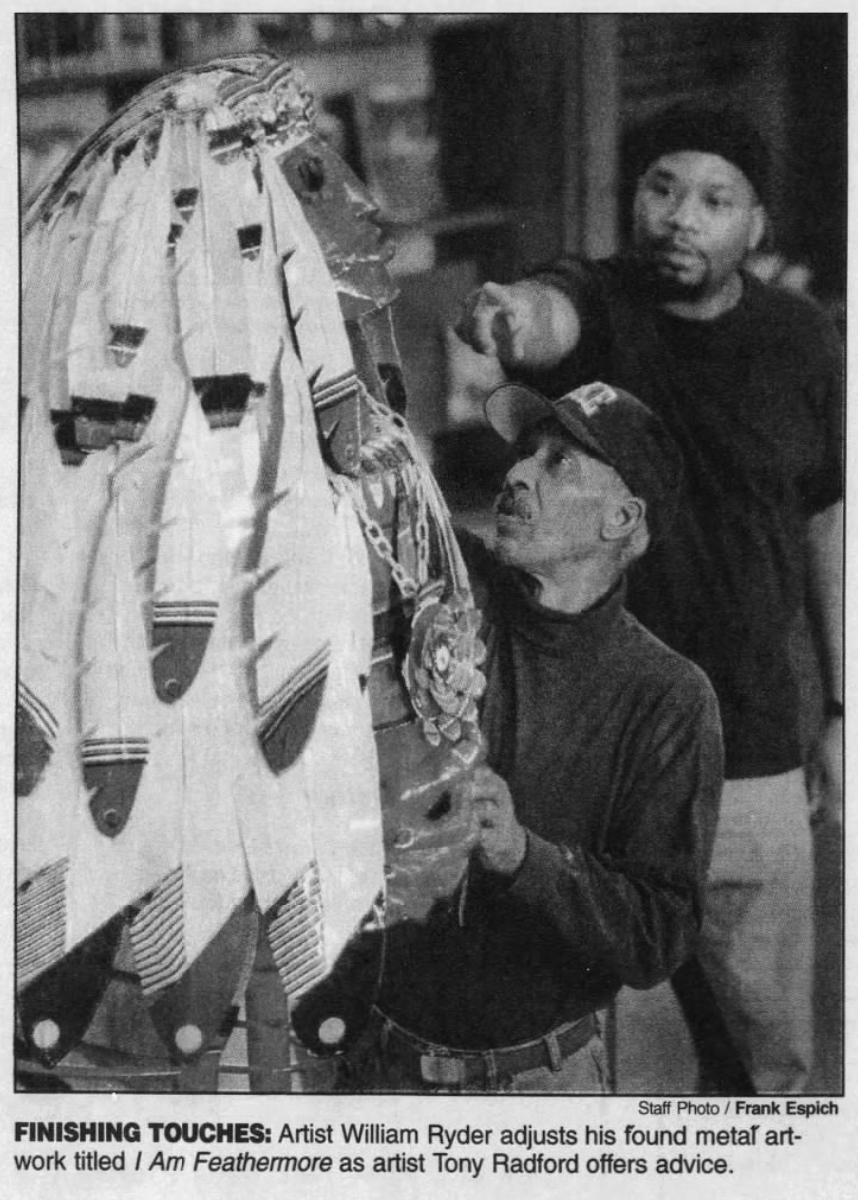

After 20 years in business, Ryder sold his printing company and turned to art at age 60. He purchased a home at 34th and Clifton streets, where houses and streets were in disrepair, but Ryder devoted himself to beautifying the area with his art. He used items others discarded or deemed useless to create sculptures that depicted the life experiences of Black men with little wealth. He sculpted jazz motifs, religious icons, and street life figures to portray the joy, pain, triumph, struggle, and despair of Black men in America.

Ryder’s eclectic style gained public attention. His paintings, sculptures, and other art installations found an audience at the and in the pages of , the , and . By the end of his life, he had created so much artwork the entire first floor of his home became a gallery of sorts.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.