Located in northern section of , the Syrian Quarter, also called the Syrian Colony, was the first Arabic-speaking neighborhood in Indianapolis. Today, sits atop the land where Arabic-speaking children once played and local journalists noted the sounds of women singing in Arabic.

These immigrants from the Eastern Mediterranean, especially from what today are Lebanon and Syria, were part of the large-scale immigration to Indiana before World War I. Half a million Arabic-speaking people left their homelands for the Americas in this era, and perhaps 100,000 of these immigrants came to the United States, with a larger number going to Latin America. By 1910, about 1,000 of them lived in Indianapolis.

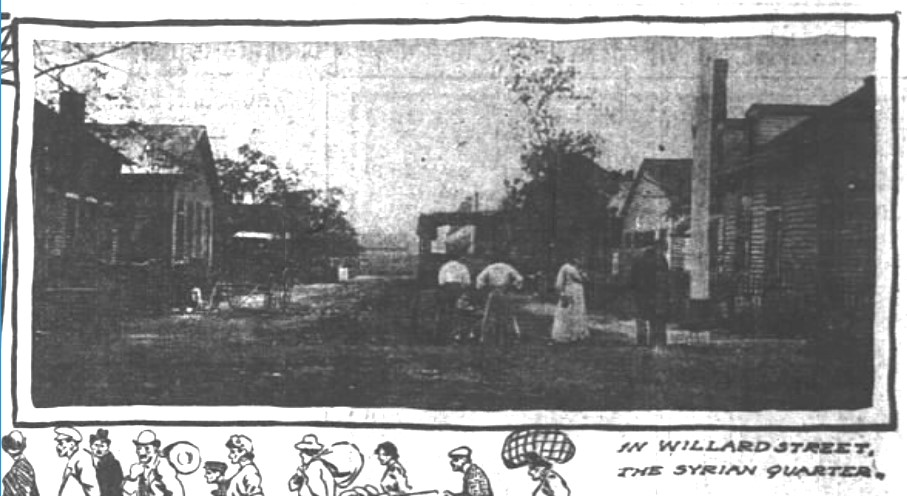

Hundreds settled on Willard Street, a road about 100 yards long that ran over creek between better-known Senate Avenue and Capitol Avenue. The described Willard Street as a “short thoroughfare divided into two parts by a dirty little stream whose banks in this particular vicinity were laden with tin cans, old shoes and other rubbish.” By 1908, Willard Street had 32 “shotgun” housing units, only 15 feet wide, and each one sometimes housed 10 or more people. Some residents worked in area factories, while others made their living as peddlers.

Even though Willard Street was known as the city’s “Syrian Colony,” were a minority of its total residents. According to a December 26, 1903, article, Italians, Poles, Greeks, and Hungarians also inhabited the street’s narrow wood-framed houses. This was a racially integrated neighborhood. Of the 179 people counted as residents of Willard Street in the 1900 U.S. Census, 55 of them were Black. There were likely other uncounted, temporary Arab residents on the street, as well.

In 1900, Syrians in Indianapolis were considered to be “Oriental,” or Asian, partly because Syria and Lebanon are indeed found in West Asia. But this racial label also revealed the xenophobia and racism that these immigrants faced. In 1893, for example, the devoted extensive, full-page coverage to Syrian immigrants living on Willard Street. The article depicted the street as an “abode of filth, vice, poverty, and disease,” repeating popular anti-immigrant tropes that associated non-white people not just with a foreign culture but also with criminality and medical pathology. Similarly, in 1896, the Indianapolis News published a story focusing on what the newspaper found to be the odd, perhaps scandalous practice of residents sleeping outside on summer nights. This reporting made the Syrians seem uncivilized and un-American in their habits.

The presence of Arabic-speaking immigrants attracted extra attention from the city’s press because Syrians were considered exotic. Elements of Mediterranean culture such as fencing and line dancing provided human interest stories for non-Arab readers. For example, in 1906 the Indianapolis News featured the story of a man whom they called “Romanos the Fencer”: “He has been the year’s one sensation on Willard Street. On Sunday mornings, Romanos, with long, white hair streaming over his shoulders, would get the young men of Willard Street into the roadway. There he taught them the art of fencing and the entire colony gathered to watch him.”

Syrian women were vital to the success of the neighborhood. If you visited during the week, said the Indianapolis Journal, you would find women rising early and working late. Since many men were away on their peddling routes often far away from Indianapolis, it was the women who gathered scraps from a nearby lumber yard to fuel their stoves. “Their daily work is quite enough to dispel all preconceived ideas regarding the indolence and helplessness of Oriental women,” wrote the Journal. The writer could not believe that such small women could carry such large loads of lumber.

In 1910, the U.S. Census counted an increase in the number of Syrians living on Willard. Of the 19 households tallied, 10 were immigrants from Syria. But the number of housing units on the street was dwindling as more of the street came to be used for industrial purposes. By 1915, the number of Syrians on Willard Street had decreased. Only 8 of the 30 homes on the street were occupied by families with explicitly Arab names: Bashhour, Freije (2), Hider (2) Kafoure (2), and Trad. Five years later, there were no more identifiably Arab names on Willard, and in the 1920s, the number of available housing units declined as the east side of the street was cleared away to build a rail line.

Some Syrians continued to live in other parts of Babe Denny, but the majority of Arab Americans were moving to the east and the west sides, where many established corner grocery stores. Their children and grandchildren would make significant contributions to Indianapolis’ economy and civil society. Their male and female children, sometimes born in Syria, sometimes born in America, attended public schools and sometimes college or university. Many served in . These Arab Americans went on to help establish in the neighborhood and the Syrian American Brotherhood on .

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.