Arabic-speaking people began settling in Indianapolis in the late 1800s. Coming mainly from what today are the countries of Syria and Lebanon, which were then part of the Ottoman Empire, these immigrants were people of modest means who arrived in the United States in search of economic opportunity.

Like so many other Hoosier families who trace their Indiana roots to this era of large-scale immigration, there were both “push and pull” factors behind migration. Life in the eastern Mediterranean, as in most of the world, was changing. Even as the global economy expanded, many people were actually worse off as their traditional ways of making a living disappeared. During the same time, U.S. businesses actively recruited unskilled labor to help fuel industrial and agricultural expansion, especially in the Midwest. As a result, over a million immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe and the Ottoman Empire came to the United States before World War I.

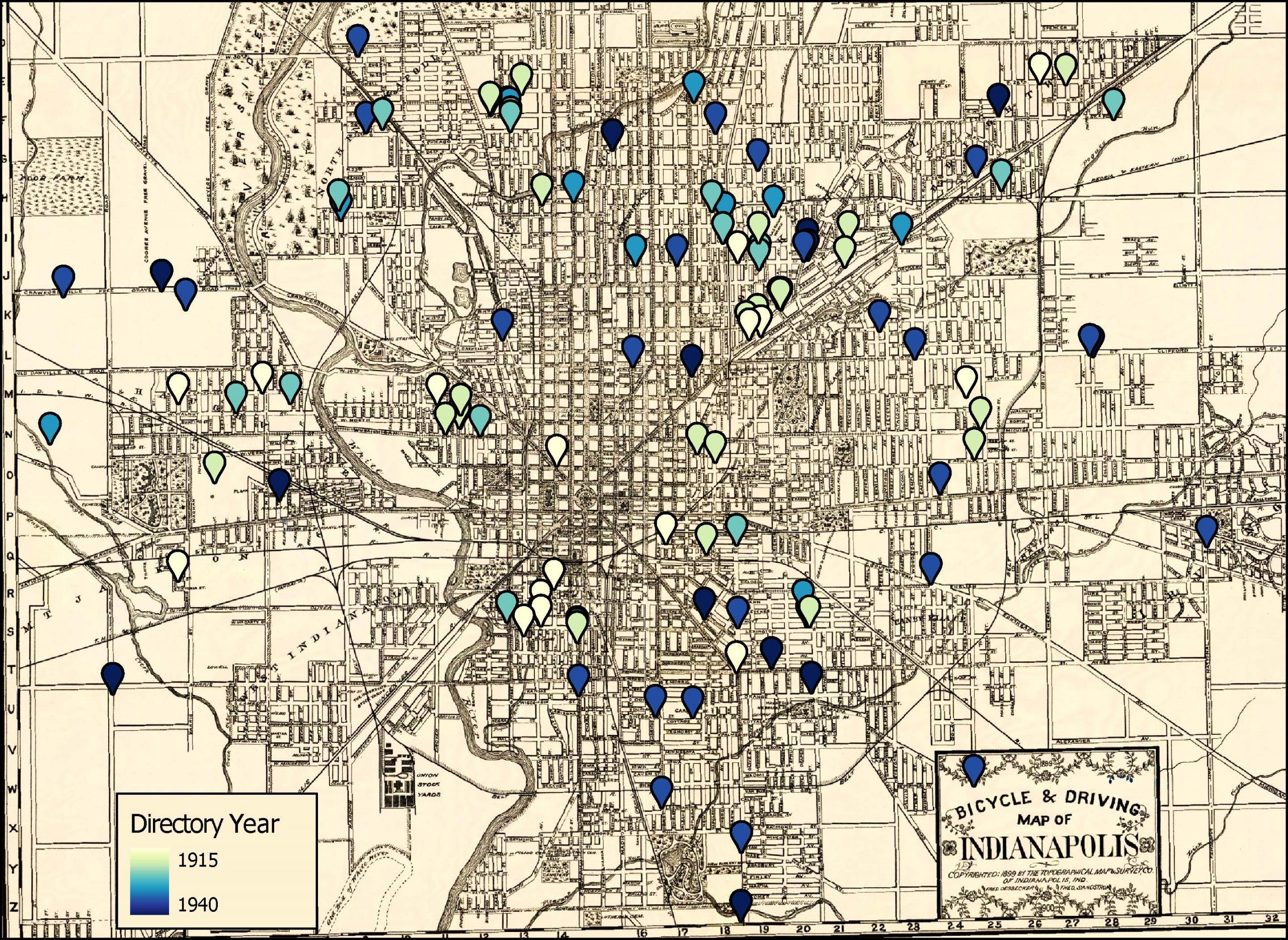

Tens of thousands of them were Arabic speakers. By 1910, there were about 1,000 people of Arab descent in Indianapolis. Some worked in area factories, while others, especially those who lived in the on Willard Street, made their living as peddlers. By , the Syrians of Indianapolis also established successful businesses, including grocery stores and retail shops.

Despite their decades-long presence in the country, there was strong anti-immigrant feeling in the country after World War I, and the 1924 National Origins Act virtually banned immigration from Syria and other parts of Asia. According to community oral histories, the Indianapolis is said to have burned at least one cross on the lawn of a Syrian immigrant. At the same time, some Arab Americans became active in several white-dominant public organizations, including the and various fraternities. Syrian and Lebanese children, both male and female, attended public schools and sometimes college. Arab Americans established community organizations, the most prominent being in the neighborhood. At the time, the vast majority of Arab Americans in Indianapolis were Christians, identifying with , , or Melkite (Greek Catholic) Christianity. ( settled in the northern part of the state, especially in Michigan City.) In the 1930s, secular ethnic organizations such as the Syrian American Brotherhood on as well as Syrian-Lebanese debutante societies offered ample opportunities for socializing, fun, and philanthropy that cut across or simply bypassed religious identities.

By the 1950s, the children of the first generation of Arabic-speaking people in Indianapolis began to make notable contributions to public life. Starting in the late 1950s, Indianapolis’ Michael Tamer and LaVonne Rashid raised all the money for Danny Thomas’ St. Jude Children’s Hospital from their office on Massachusetts Avenue. The philanthropic organization they ran, the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities, emerged as the largest single Arab American philanthropic organization. In 1964, Terre Haute’s Helen Corey became the first statewide Arab American office holder, elected as the 23rd Reporter of the Indiana Supreme and Appellate Courts with over 1.1 million votes. In 1972, Dr. William K. Nasser helped to establish cardiology group, which would become one of the largest such organizations in the country. The grandchildren of the first generation would achieve even greater fame: Warren Central’s Jeff George was the first overall selection by the in the 1990 National Football League draft, and Mitch Elias Daniels Jr. became governor of the state in 2004.

Because Arabic-speaking people were largely prevented from immigrating to the United States by the 1924 immigration laws, it was not until the 1965 passage of the Hart-Cellar Immigration and Naturalization Act that Indianapolis saw larger numbers of Arabic-speaking immigrants. A number of the new immigrants were healthcare professionals, scientists, and engineers. Taking up employment in area hospitals, universities, and companies such as , they came to play prominent roles in the area’s economic growth during the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Both Christians and Muslims immigrated for what they saw as an unprecedented economic opportunity as well as the freedom to practice their religion without government interference or repression. Among the most prominent Arab American leaders in Central Indiana to emerge in this generation was State Senator Fady Qaddoura, a Palestinian refugee from Ramallah and former City of Indianapolis who defeated John Ruckelshaus in the 2020 election.

Some Arab immigrants, especially political exiles and refugees, came to Indianapolis to escape repression or violence in their homelands. Events such as the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, the 1975 Lebanese Civil War, the 1991 Somali Civil War, the 1992 military coup in Algeria, the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, and the 2011 Syrian Civil War resulted in an increase in the Arabic-speaking population of Indianapolis. Often assumed to be Muslim, these newly-arrived Arab Americans were sometimes victimized by Islamophobia, anti-Muslim bias, discrimination, and violence. In 2015, for example, Indiana governor Michael Pence attempted to prevent Syrian refugees from resettling in Indiana. Various central Indiana leaders, including Catholic Archbishop Joseph Tobin, opposed Pence, and the federal Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the illegality of Pence’s anti-refugee policy. Other civil society groups, including , Exodus, and , joined area businesses and educational institutions to aid Arabic-speaking immigrants and refugees to central Indiana.

In 2021, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated that there were 20,856 Hoosiers of Arab descent. was home to 5,688 Arab Americans while 4,286 lived in . These two Central Indiana counties accounted for almost a third of all Arab Hoosiers. People who trace their ancestry to Lebanon were the largest single group of Arab Americans in the state. But from 2009 to 2016, there were significant increases in the number of immigrants from Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Morocco, and Yemen. Immigrants also arrived from Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Qatar, and Kuwait. According to the Arab American Institute, these numbers from the U.S. Census Bureau likely underestimate the number of Arab-descended people in Arab Indianapolis.

FURTHER READING

- “Arab Indianapolis.” https://arabindianapolis.com/.

CITE THIS ENTRY

APA:

Curtis, E. (2022). Arab Americans. Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Retrieved Mar 7, 2026, from https://indyencyclopedia.org/arab-americans/.

MLA:

Curtis, Edward E., IV. “Arab Americans.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2022, https://indyencyclopedia.org/arab-americans/. Accessed 7 Mar 2026.

Chicago:

Curtis, Edward E., IV. “Arab Americans.” Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, 2022. Accessed Mar 7, 2026. https://indyencyclopedia.org/arab-americans/.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.