Photo info …

Credit: Madam C.J. Walker Collection, Indiana Historical SocietyView Source

(Dec. 23, 1867–May 25, 1919). Madam C. J. Walker arrived in Indianapolis in February 1910, attracted by its thriving indiana avenue business community, access to for her mail-order operation, and respect for progressive leaders like publisher and physician . That year the city’s 21,816 Black residents comprised 10 percent of the local population and were the nation’s sixth-largest urban Black enclave.

Born Sarah Breedlove in Delta, Louisiana, on the same cotton plantation where her parents and older siblings had been enslaved before the Civil War, she was orphaned by age 7. At 14, she married Moses McWilliams, who died around 1888 when she was 20. That year she and their three-year-old daughter, Lelia (who later would be known as A’Lelia Walker), moved from Vicksburg, Mississippi, to St. Louis where her three older brothers were barbers. Having little formal education, she worked as a laundress, making as little as $1.50 a week.

The young widow joined St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church where she was mentored by the women of the congregation. As a member of the choir and the women’s missionary society, she was exposed to educated, accomplished teachers and civic leaders, many of whom belonged to the National Association of Colored Women.

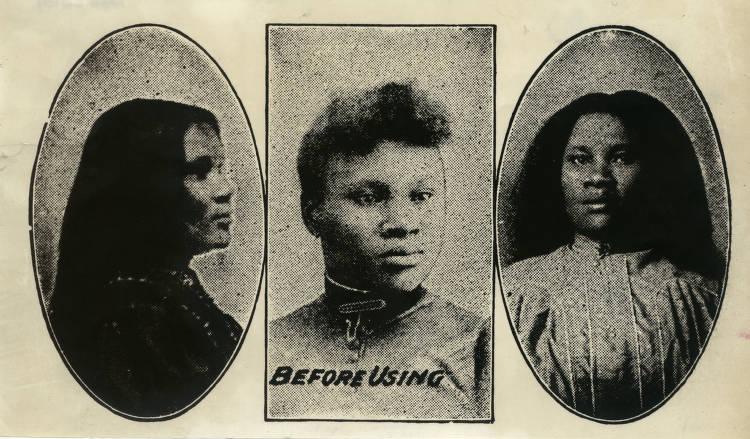

Around 1900, after developing a severe scalp ailment that caused her to lose most of her hair, she experimented with curative remedies and commercial hair dressings, briefly selling the products of St. Louis resident Annie Turnbo Malone, who would become her primary competitor. In 1905, she moved to Denver where a widowed sister-in-law and four nieces lived in the city’s Five Points neighborhood. While working as a cook for a local pharmacist, she perfected her formula to treat dandruff and cure scalp infections that were quite common during an era when most Americans lacked indoor plumbing.

In January 1906, she married Charles Joseph Walker, her third husband, a St. Louis newspaper sales agent, who moved to Denver and helped design her early advertisements. Following a custom affected by some businesswomen of the time, she adopted her husband’s surname and added the title “Madam” for her new enterprise, the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. They divorced in 1912.

In 1908, after a year and a half of traveling throughout the southwestern, southern, and eastern United States, the couple briefly settled in Pittsburgh where Walker opened Lelia College of Beauty Culture – named for her daughter – to train sales agents and beauty culturists.

Walker’s arrival in Indianapolis in 1910 coincided with the beginning of a campaign to construct the , part of a national initiative to build Young Men Christian Association facilities in Black communities in several American cities. Her $1,000 contribution to the building fund launched her reputation as a philanthropist.

Walker immersed herself in the civic and social activities of the city, joining and the local chapters of the National Negro Business League and of the Court of Calanthe, the women’s auxiliary of the Black Knights of Pythias. She purchased a home at 640 N. West Street (now Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Street) and remodeled a stable and warehouse at the rear of the property into a factory and office.

In 1911 Attorney , who would become Indiana’s first Black state senator, drafted the articles of incorporation for the Walker Company. Walker recruited Alice Kelly, the former dean of girls at a Kentucky boarding school, to manage her factory, and persuaded attorney to become her general manager, a position he held until his death in 1947.

In June 1912, eight years before the ratification of the 19th Amendment guaranteed women’s right to vote in federal elections, Walker hosted meetings of the Colored Branch of the Indiana Equal Suffrage Association in her home. She served as treasurer for the interest group that eventually led to the . As a patron of the arts, she commissioned portraits by and and hosted events where performed.

In 1913, Walker traveled to Cuba, Haiti, Jamaica, Costa Rica, and the Panama Canal Zone to expand her international sales into markets heavily populated by people of African descent.

Through her extensive travels and engagement with national Black organizations, Walker had developed friendships with other leaders including educators Booker T. Washington and Mary McLeod Bethune, anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells, officers James Weldon Johnson and W. E. B. DuBois, and Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters founder A. Philip Randolph. Increasingly involved in civil rights causes, she moved three years later to New York where her daughter had opened a Walker beauty school and hair salon just as that community was becoming a Black cultural and political mecca. The Walker Company headquarters, however, remained in Indianapolis with day-to-day operations managed by Ransom and Kelly.

By 1917 when Walker hosted her first national convention of her sales agents in Philadelphia, she claimed to have trained nearly 20,000 former maids, cooks, teachers, and farm laborers in the Walker System of Beauty Culture. What had begun as an enterprise focused on beauty products now offered a vehicle for financial independence and generational wealth for African Americans who were largely shut out of educational and job opportunities at a time when housing, public transportation, and public facilities were segregated by law in many states and by custom in others.

Walker gave annual prizes not only to the women who had sold the most containers of Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower or recruited the most agents but also to those whose local Walker clubs had contributed the most time and money to charity in their communities. Indicative of her increasing political activism, she had become a member of the Harlem committee that organized the Negro Silent Protest Parade in response to the July 1917 East St. Louis massacre. At the end of her 1917 convention, the delegates sent a telegram to President Woodrow Wilson urging him to support legislation to make lynching a federal crime.

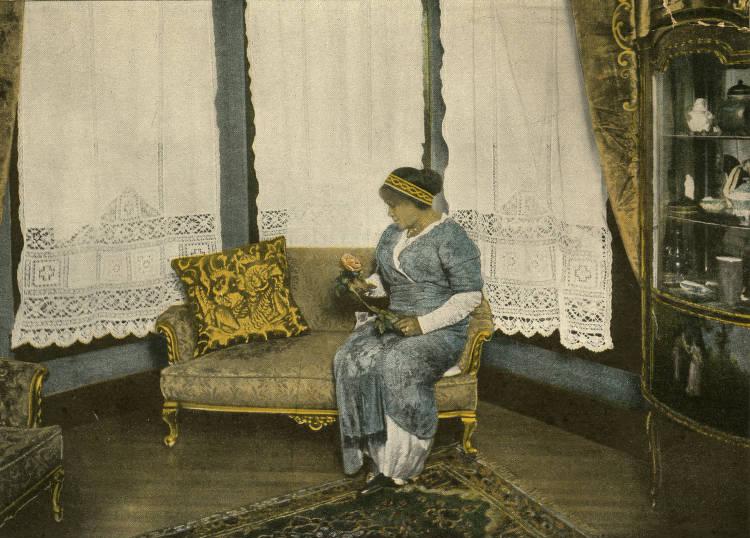

In the spring of 1918, Walker moved into Villa Lewaro, the Irvington-on-Hudson, New York estate she had commissioned architect Vertner Woodson Tandy to design. At the opening reception in August 1918, she honored Emmett Scott, special assistant to the secretary of war for Negro affairs, and spoke out publicly to demand improved treatment and better facilities for Black officers and enlisted men who were stationed on American bases and French battlefields during World War I.

Throughout her adult life, Walker provided scholarships for students at several Black colleges and boarding schools as well as financial support for orphanages, retirement homes, YMCAs, YWCAs, political causes, and the fund to preserve the home of abolitionist Frederick Douglass in Washington, D.C.’s Anacostia neighborhood. Just before she died on May 25, 1919, she bequeathed $100,000 to more than 30 organizations and individuals, including $5,000 to the NAACP’s anti-lynching fund and $5,000 to Indianapolis’s .

Obituaries in dozens of American newspapers called her the wealthiest Black woman in America. lists her as the first American woman to become a millionaire through her own business efforts.

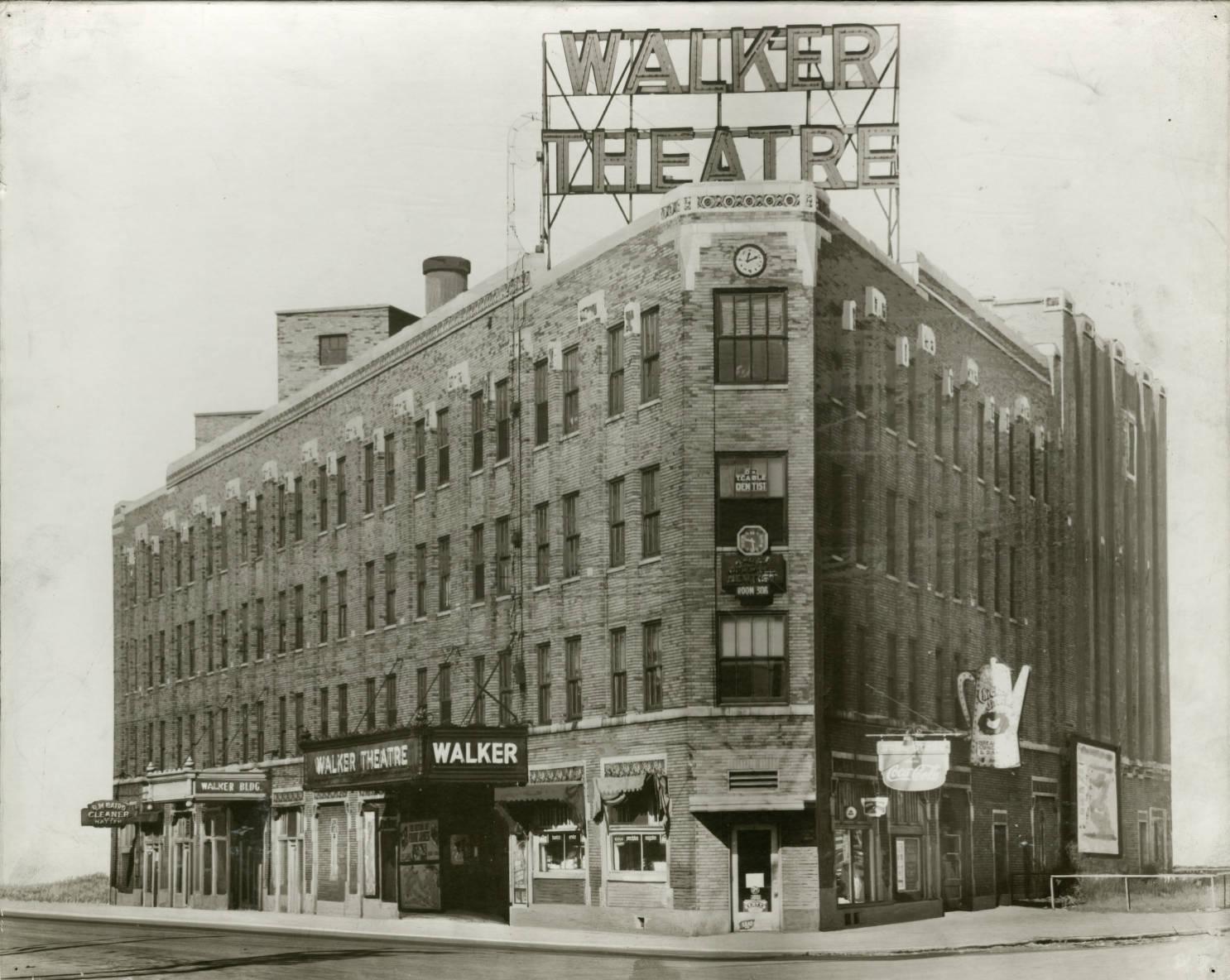

During the 1990s, she was honored by the U.S. Postal Services with a Black Heritage Series stamp and inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame and the Junior Achievement National Business Hall of Fame. There are two National Historic Landmarks associated with her legacy: The and Villa Lewaro. In 2016, Sundial Brands launched Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culture, a line of hair care products inspired by Walker’s system.

In 2019, the Indiana Historical Society opened a Madam Walker exhibition and digitized more than 40,000 documents from its large Madam Walker Collection. In 2020, a four-part television series Self Made, inspired by Walker’s life and starring Academy Award winner Octavia Spencer, aired on Netflix.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.