The Indianapolis ABCs were a powerhouse team of early Black baseball. After a so-called “gentlemen’s agreement” segregated organized baseball during the 1880s, communities formed their own amateur clubs. Over time the best clubs developed into semiprofessional and professional teams. Around 1900, Indianapolis already had a significant African American population, with many informal clubs playing on neighborhood sandlots, and some forming around organizations like and local businesses. In 1907, local Black saloon keeper Randolph “Ran” Butler initially formed and managed the ABCs as a marketing effort for the American Brewing Company (see ). As the marketing focus faded, the team gained a reputation for playing high-quality semiprofessional baseball.

In 1912, white businessman Thomas Bowser purchased the club from Butler with great plans. In 1914, he lured manager north from West Baden, where he had managed the southern Indiana resort’s Sprudels team since 1909. One of the best minds in early Black baseball, Taylor purchased a half-interest in the ABCs. He also had three brothers who played for the team at one time or another: pitcher John Boyce “Steel Arm Johnny;” third baseman James Allen “Candy Jim;” and first baseman Ben, a future Hall of Famer (2006). All college-educated, the Taylors had been raised by a Methodist minister father.

Taylor’s strict, religious upbringing influenced his managerial style, and many of the players he signed had, like him, either attended college or served in the military. So, they were accustomed to his demands for discipline both on and off the field. Adhering to Taylor’s regimen, which included wearing collars, ties, and shined shoes when not in uniform, the ABCs became role models for the Black youth in Indianapolis. Supporting the , C. I. Taylor believed playing and behaving in a gentlemanly manner would make white society more inclined to recognize Black baseball’s merits.

Taylor’s reputation helped him gather top talent, and in 1915, the ABCs added a star when 18-year-old Indianapolis native returned home after serving three years in the 24th Infantry. Nicknamed “The Hoosier Comet,” the speedy centerfielder was compared to white contemporaries as “The Black Ty Cobb” for his base stealing, “The Black Tris Speaker” for his fielding, and “The Black Babe Ruth” for his slugging power. Charleston was inducted into Cooperstown’s Baseball Hall of Fame in 1976.

Although Black baseball had no formal leagues in 1915 and 1916, the ABCs claimed the western championship in heated rivalry with Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants. These were the team’s glory years, but all was not well with the owners. Before the 1916 season, Bowser and Taylor argued and split ways, dividing the team. Much shifting of rosters occurred during the season, but most top players eventually landed with Taylor’s ABCs.

The ABCs played most of their home games at three Indianapolis ballparks. Northwestern Park was a modest wooden structure located in the city’s Black community, northwest of West 17th Street and Northwestern (now Martin Luther King) Boulevard. C. I. Taylor leased other parks to accommodate crowds for big games, like Sunday doubleheaders against major rivals. In 1915, after the short-lived Federal League Hoosiers (white) team left Indianapolis, Taylor leased their still-new concrete and steel stadium at Kentucky and River Avenues (on a portion of the property purchased in 2022 to build a stadium for the professional soccer team). Although farther away, this major league ballpark was Taylor’s best option because it had no limitations against Black players or fans.

The solution was short-lived. After Federal League Park was demolished in 1917, Taylor reached an agreement with the to occasionally lease (where the is today); however, the ABCs were not allowed to use the locker rooms. As a remedy, Taylor created changing space in his business, had his players dress there, and often organized parades down the avenue and across Washington Street to the ballpark. These were grand events, with cars, bands, and civic groups escorting their Indianapolis ABCs to victory.

World War I made times difficult for baseball. When the United States instituted the draft in June 1917, Taylor took all eligible members of his team to sign up together, meaning players could be called to serve at any time. The team played through hardships in 1917 and 1918, but after that season, Taylor decided to take a year off until all the soldiers could return.

During his 1919 season away from the ABCs, Taylor worked toward developing a formal league for his team. He and sportswriter Dave Wyatt used the Black press to promote their ideas for what would make the league successful. In February 1920, when owners of the strongest midwestern teams met in Kansas City to establish the Negro National League (NNL), their concepts became the heart of its constitution. Rube Foster was named league president, Taylor vice president, and Wyatt eventually became secretary.

The first game of the Negro National League was held in Indianapolis on May 2, 1920, at Washington Park, where 6,000 fans watched the ABCs defeat Joe Greene’s Chicago (Union) Giants 4-2. In addition to Charleston and Ben Taylor, that ABCs team also had a third future Hall of Famer—slugging catcher Biz Mackey (2006). The ABCs finished the first NNL season with a winning record (39-35) but in fourth place. But C. I. Taylor and Dave Wyatt’s vision for the league had not been fulfilled. With unbalanced schedules, teams played an uneven number of games, faced unequal competition, and did not share prime dates. These problems led to grossly uneven team profits. The league faltered, with some teams leaving and others losing players to wealthier owners. This proved devastating for the 1921 ABCs, who lost Oscar Charleston to the St. Louis Giants and fell to fifth place in the NNL.

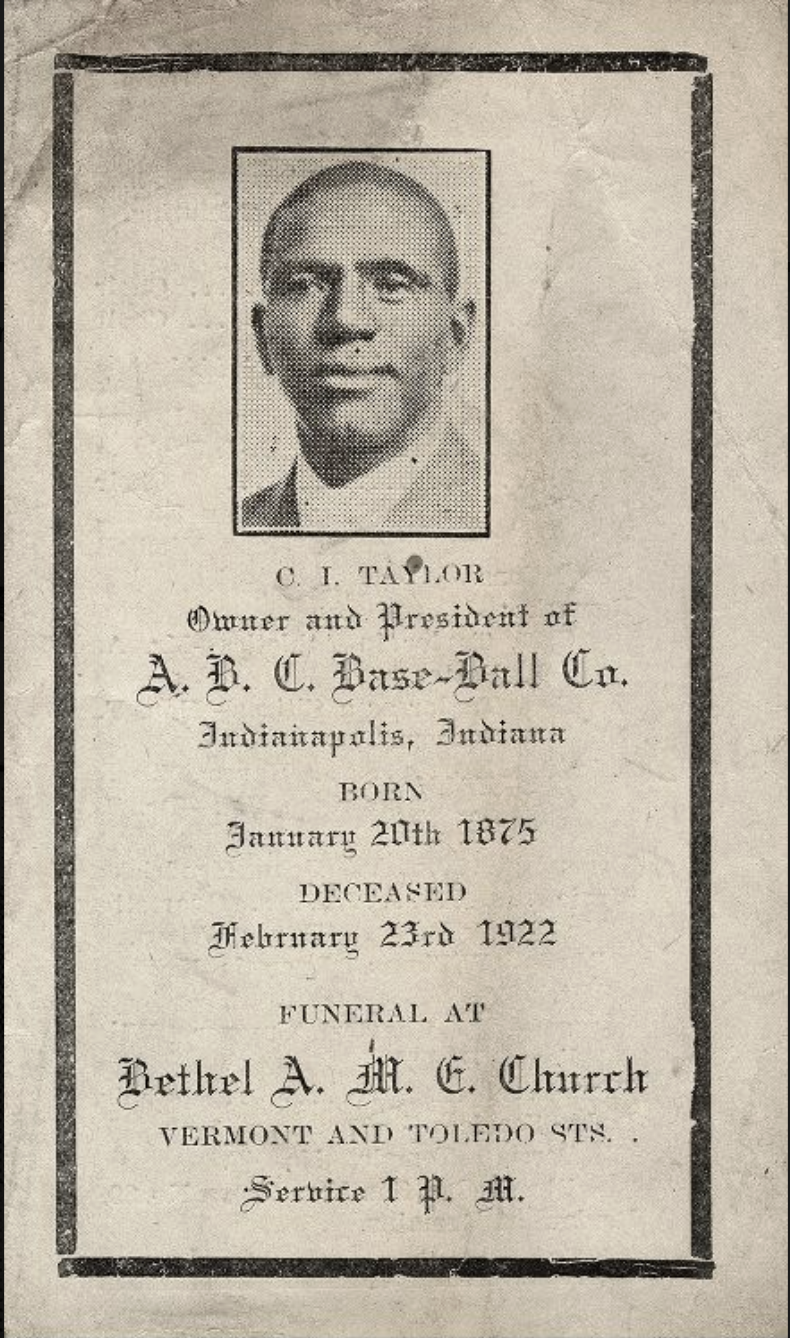

The ABCs were not the only team to struggle in 1921, so at the end of the season, many doubted the Negro National League would be able to continue. C. I. Taylor recognized the reasons and attended the league’s February 1922 Chicago winter meetings prepared to convince other owners to stay committed. He succeeded but fell seriously ill with pneumonia and died soon after returning to Indianapolis.

After Taylor’s death, ownership of the ABCs passed to his wife Olivia, and brother Ben took over as manager. Charleston returned to Indianapolis, but things were never the same. The ABCs faced financial troubles, and players began jumping to other teams. Many left for the new Eastern Colored League, including first baseman Taylor and catcher Mackey in 1923 and Charleston in 1924. The ABCs began the 1924 season with a greatly diminished roster and were dropped by the league mid-season after a dismal 4-17 start. Black businessman Warner Jewel tried to reestablish an ABCs team in 1925, but the weak effort folded halfway through the 1926 season. What was left of the franchise moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where the team became the Cleveland Hornets.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.