The general geology of Marion County, gently dipping sedimentary rocks overlaid by glacial deposits, is similar to many other areas of the Midwest. The details of the local geology, however, are more specific to Marion County. The surface of the county is part of the physiographic province called the Tipton Till Plain. This flat to gently rolling land surface is named after Tipton County (two counties north of Marion County) and is underlain by glacial deposits, the most common type being “till.”

In Marion County, the rolling surface is at elevations between about 650 and 900 ft. (about 200 and 275 m) above sea level. The West Fork of and its tributaries drain most of Marion County. Buck Creek drains a narrow part of the southeastern margin of the county. White River enters the county at the north-central county line and flows south-southwest as it passes near downtown Indianapolis to exit the county at the southwest-central county line. , the largest tributary on the east side, enters the county in the northeast corner and flows southwest until it joins White River at 10th Street near downtown Indianapolis.

In fact, the original site selected for the new city in 1820 was located on the east bank of the White River at its junction with Fall Creek. (At that time Fall Creek joined White River farther south, near Washington Street.) The largest tributary on the west side is Eagle Creek, which enters the county in the northwest corner and flows southeast until it joins White River in the southwestern part of the city.

Surficial Geology

About 2 million years ago an Ice Age began that resulted in several continental glaciers spread over Canada and the United States north of approximately the Ohio and Missouri rivers. In central Indiana, this glaciation eventually extended to the area about 35 miles (60 km) south of Marion County, with other lobes of the glacier extending much farther south in the southeastern and southwestern parts of Indiana.

About 22,000 years ago, the glacier retreated northward, leaving the county about 18,000 years ago. The various deposits of materials that had been carried by the glacier as it advanced over the area but were left behind when the glacier melted away provide evidence that the glacier once covered Marion County. These surficial materials are of utmost importance because they are the basic materials on which other factors act or depend. Thus, the soils that have supported agriculture from the beginning of settlement are developed from the weathering of the parent surficial materials.

The surficial materials, especially those composed of sand and gravel, are a primary repository of underground well water, as well as being a prime source of sand and gravel for the construction industry throughout Marion County. Most of the surficial materials in Marion County consist of glacial deposits that range in thickness from 16 to 350 ft. (5 to 107 m).

Regionally, these deposits are related to Pleistocene (2 million years to 10,000 years ago) glaciation, although only Wisconsinan deposits (about 75,000 to 18,000 years ago) are exposed in the county. The main glacial deposit is a widespread till (material ranging in size from clay to boulders that had been carried by the glacier but that was laid down under the glacier when it melted away or that flowed out from the margins of the glacier). This till blankets the upland surfaces in the county between major streams.

The second most widespread glacial deposit is outwash (material that is washed out from the margins of the glacier by meltwater as the glacier is melting). The outwash consists of sand and sandy gravel, which typically occurs along the major streams as terraces. The original site of Indianapolis was on such a terrace as is much of the downtown area of the modern city. Other small and isolated deposits of sand and gravel called kames, which were entrapped in pockets along the ice margin or in crevasses on the glacier, occur mostly in the southern part of the county. Relatively minor amounts of sand, silt, and clay occur along the major stream valleys, deposited there over the centuries by the running water.

Soils

The soils in Marion County are developed mostly from glacial deposits and to a lesser extent from the alluvial strips along the major valley bottoms. The most widespread soils in the county are the Brookston silty clay loam (composed of sand and clay), very deep soils formed in as much as 20 inches (51 cm) of silty material and the underlying loamy till, and the Miami and Crosby silt loams that develop from glacial till on upland gentle slopes and that have a seasonal high water table at 0.5 to 2.0 ft. Other soils include Fox and Ockley silt loam, very deep, soils that form on outwash terraces along the White River valley and parts of the Eagle Creek valley, and Genessee silt loam that forms on the alluvial bottomlands (flood plains) of these valleys. The Brookston and Crosby soils are poorly drained, whereas the other soils are well-drained.

Bedrock Geology

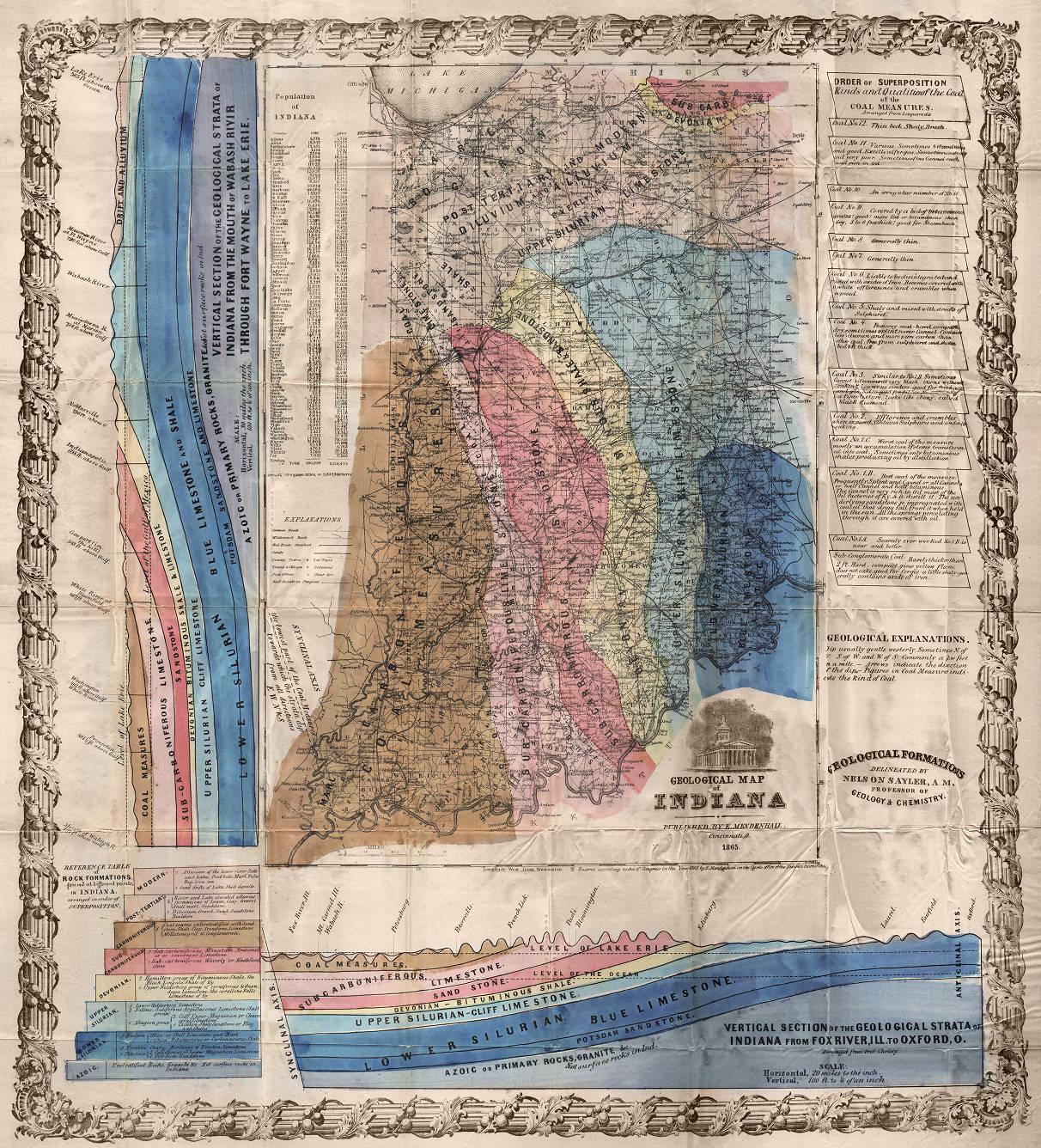

The bedrock structure of Indiana is geologically simple: from an axis trending from the southeastern to the northeastern corners of the state, the rock formations dip gently southwest into the Illinois Basin or north into the Michigan Basin. Marion County lies on the southwest dipping area, but, because of the glacial cover, bedrock is not exposed anywhere in the county except where quarrying and underground mining activities have removed the covering material.

The youngest bedrock unit in Marion County is the Borden Group of sandstone and shale of Early Mississippian age (about 350 million years ago). The next older unit (C in Figure 1) is the New Albany Shale of Late Devonian to Early Mississippian age (about 370— 350 million years ago). This formation is a potential source for petroleum products in the future.

The next older bedrock unit (B in Figure 1) consists of several limestone and dolomite formations of Middle Devonian age (380 million years ago) and Silurian age (420 million years ago). The limestone is quarried or mined at several places in Marion County for use as crushed stone or aggregate in the construction industry and at deeper levels is a major bedrock aquifer for well water.

The next older bedrock unit (A in Figure 1) is shale of Late Ordovician age (about 440 million years ago), which is underlain by about 4,000 ft. (about 1,220 m) of limestone, dolomite (composed of calcium magnesium carbonate), shale, and sandstone extending back to the Late Cambrian age (about 525 million years ago). All of these sedimentary rocks rest on a basement complex of granitic rocks.

Geologic History

Beginning about 525 million years ago a shallow sea moved across Marion County, which had been undergoing erosion of a basement complex. During the interval until about 350 million years ago, the sea fluctuated over Indiana with Marion County being the site for the deposition of various types of sediments depending on the relative position of the shoreline.

The evidence for what happened next is missing. The tilting of the bedrock formations occurred sometime after 350 million years ago, probably during the earth movements associated with the development of the Appalachian Mountains, ending about 250 million years ago. There may well have been more sediments deposited, but erosion stripped away any such deposits sometime before the onset of glaciation.

About 2 million years ago an ice age began with glaciation gradually expanding until about one-third of North America, eventually including Indiana and Marion County, was covered by an ice sheet. Marion County was quite hilly, with relief up to 425 ft. (about 130 m), but as the glaciers moved back and forth across the area they gradually filled in the valleys with glacial deposits and covered the hills. The glaciers left the county about 18,000 years ago, leaving the landscape pretty much what we see today, taking into consideration the modifying effects of climatic changes and weathering that follow a shift from a polar to a temperate climate.

Hydrogeology of Marion County

Strategically placed reservoirs (Eagle Creek, , and ) and wellfields have provided Marion County and the City of Indianapolis with an abundance of available water to meet the needs of a growing population along with agriculture, industrial, and energy uses and development.

Marion County is located within the White and West Fork White River Basin, except for the southeastern portion, which is located within the East Fork White River Basin. In addition to the surface hydrology in Marion County, there are unconsolidated and bedrock aquifers sufficient for domestic and high capacity withdrawal. Approximately 81 percent of all water wells in this county are completed in unconsolidated deposits.

The unconsolidated aquifer systems of Marion County are composed of sediments deposited by, or resulting from, a complex sequence of glaciers, glacial meltwaters, and post-glacial precipitation events. The most recent glaciation, the Wisconsin glaciation, deposited sediments in Indiana 21,000 to 13,600 years ago. Six unconsolidated aquifer systems have been mapped in Marion County: the Till Veneer; the New Castle/Tipton Till; the New Castle/Tipton Till Subsystem; the New Castle/Tipton Complex; the White River and Tributaries Outwash; and the White River and Tributaries Outwash Subsystem. Because of the complicated glacial geology, boundaries of the aquifer systems are commonly gradational and individual aquifers may extend across aquifer system boundaries.

The most extensive of the unconsolidated aquifers in Marion County is the New Castle/Tipton Till System, which is primarily of glacial till with intertill sand and gravel. It is up to 305 feet in thickness and capable of meeting the needs of most domestic users with a yield ranging from 10 to 50 gallons per minute and some high-capacity users with yields ranging from 70 to 430 gallons per minute. The White River and Tributaries Outwash System exists along the White River and its tributaries and consists of thick glacial sand and gravel and is generally capped by a clay unit. Domestic yields are generally up to 50 gallons per minute, and high-capacity wells have a yield ranging from 70 to 3,040 gallons per minute.

In areas with thin or less productive unconsolidated aquifers, wells are drilled to the underlying bedrock units. Three bedrock aquifer systems are identified within Marion County. They are, from youngest to oldest and from west to east: the Borden Group of Mississippian age; the New Albany Shale of Devonian and Mississippian age; and the Silurian and Devonian Carbonates. Depth to bedrock ranges from outcropping along a relatively small area of the White River in the north-central section of Marion County, to being overlain by unconsolidated deposits up to about 305 feet thick in the northeast. Approximately 19 percent of all wells are completed in bedrock.

The Silurian and Devonian Carbonates Aquifer System is the primary bedrock aquifer. It meets the needs of domestic and some high-capacity users. Typical domestic yields are 10 gallons per min or greater. High-capacity wells have reported yields from 93 to 1,200 gallons per min. The Borden Group and New Albany Shale have limited groundwater resources and in many areas are considered an aquitard (an impermeable layer).

The potentiometric surface is a measure of the pressure on water in a water-bearing formation. The potentiometric surface is estimated by static water levels measured upon the installation of a water well and given as elevation in feet above mean sea level (ft msl). The unconsolidated potentiometric surface ranges from a high of 840 ft msl in the east-central portion of the county to a low of 640 ft msl in the south-central portion. The bedrock potentiometric surface elevations range from a high of 820 ft msl in the northwest corner near Boone County to a low of 650 ft msl in the south-central portion. The majority of Marion County groundwater, unconsolidated and bedrock, flows toward White River.

Help improve this entry

Contribute information, offer corrections, suggest images.

You can also recommend new entries related to this topic.